Death from Above | History Today - 5 minutes read

In the late summer of 1917, as a weary and grieving Britain braced itself for a fourth year of the First World War, a battle against a millions-strong and hugely destructive enemy was also being waged in the heart of London.

The site of this other battle was the great hammer beam roof of Westminster Hall, recently on view during the lying in state of Queen Elizabeth II. The enemy was a tiny, seven-millimetre-long beetle, whose wood boring was threatening to bring the entire edifice crashing down. The Hall, built by William II, was an unbroken thread linking modern Britain to the Norman Conquest and the roof, constructed using 600 tonnes of oak from the forests of southern England, was added in 1393 by Richard II. It had seen debates from the earliest parliaments and the trials of Charles I, William Wallace and Guy Fawkes. If the roof had caved in during this moment of jeopardy for the country, it would have dealt a devastating blow to an already disheartened population.

Palace of Westminster architects had known for decades that the roof of the Hall was under attack from the death-watch beetle and various attempts to halt the steady weakening of the ancient timbers had been tried, but in the days before chemical pesticides all had failed. Xestobium rufovillosum bores holes in the timbers for its larvae which then burrow further into the heart of old hardwood beams where they live, sometimes for years, steadily undermining the wood fibres from within. During a routine inspection of the timbers in 1913 much worse damage than anticipated was discovered: the Manchester Guardian reported, colourfully: ‘This noxious little beast … is so efficient that some of the holes it has made in the oak trusses would take a man up to his waist.’ Four out of the 13 trusses were in danger of collapse and ‘a forest of scaffolding’ was erected to support the 600-year-old roof. In April 1914 the 83-year-old Liberal peer Sir Thomas Roe and the government whip William Jones MP climbed into the roof to inspect the damage for themselves. It was clear that more than scaffolding was needed to prevent the roof from disintegrating completely. Harold Maxwell-Lefroy, Professor of Economic Entomology at Imperial College, London and honorary curator of insects at London Zoo, was called in.

Maxwell-Lefroy was a flamboyant and often controversial scientist who rose to fame as government entomologist at the Department of Agriculture in India in the early 20th century, where he was charged with solving the Empire’s various and intractable insect-related problems. The insects of India, Australia, Africa and the Caribbean, unheard of in damp, cool Britain, destroyed crops, ate through wooden buildings and spread disease. Worst of all, the termites – the ‘white ants’ of Southeast Asia – threatened the very foundations of colonial bureaucracy for they ate paper and destroyed judicial records, promissory and currency notes, registers, indexes, dictionaries, maps and books.

Maxwell-Lefroy became famous for developing insecticides based on research published in his book Indian Insect Pests (1906). His preparations killed not only termites but other destroyers of the Empire’s sources of wealth, including the tobacco caterpillar and pests that threatened the Indian silk industry. On his return to England to take up his post at Imperial College, he was made honorary curator of the Insect House at London Zoo and transformed it from a dowdy collection of huts to the world-famous Caird Insect House. The Insect House opened in the autumn of 1913, heralded as one of the first in the world to use ‘aquarium principle lighting’, in which the public corridors were darkened and the exhibits lit from within, creating a magical effect to show visitors enormous bird-eating spiders and water beetles with opalescent wing cases in illuminated glass cabinets.

The most popular exhibits were the peacock butterflies with their dazzling wings. Opposite the butterflies the amber, gold and green atlas moths, among the largest insects in the world with a wingspan far greater than a human hand, flew among tropical foliage. The Insect House became so popular that in the Easter holidays of 1914 policemen were brought in to control and direct the crowds as they swarmed into the darkened corridors.

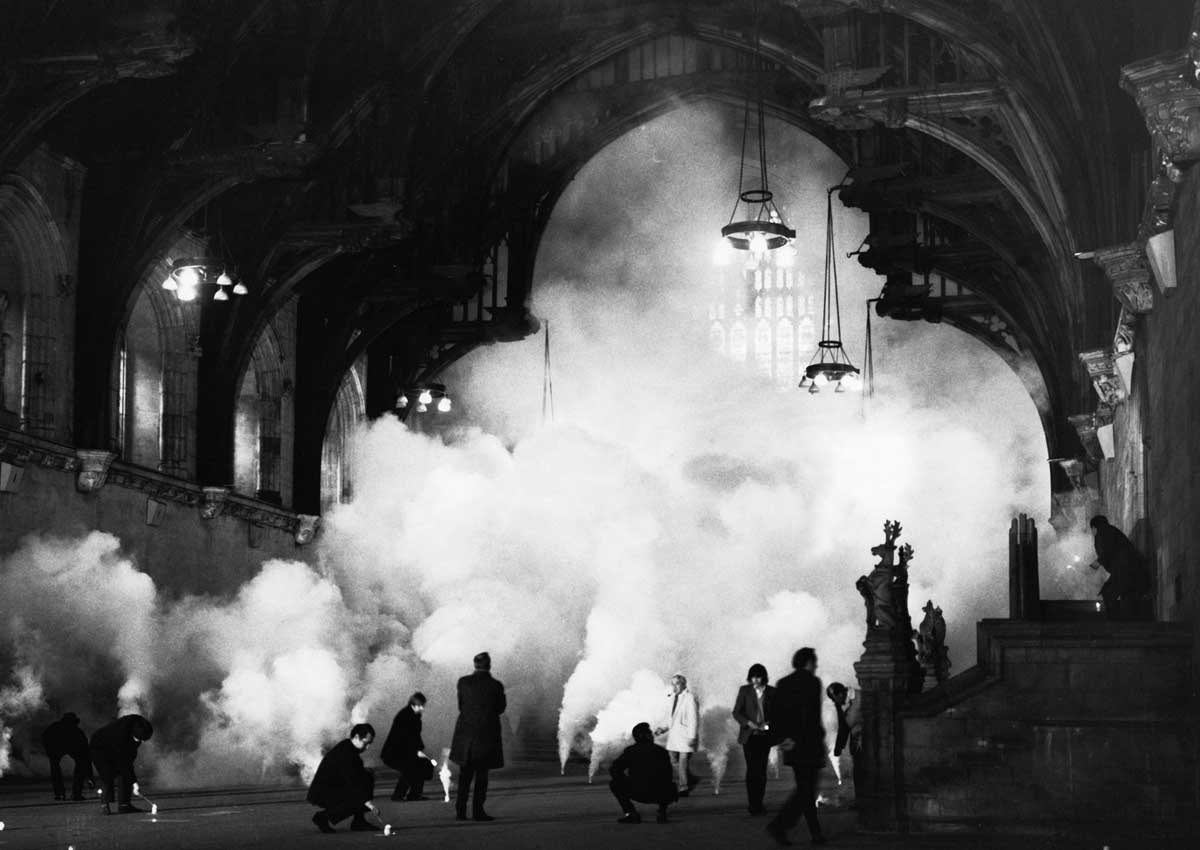

Who better to come up with a solution to the death-watch beetle problem of Westminster Hall. In August 1917 Maxwell-Lefroy and his team of gas-masked workmen ascended the scaffolding on 60-foot-high ladders and drenched the beams with a preparation of cedarwood oil, paraffin wax and solvent that he had invented in his laboratory at Imperial. It was reported in the press that, in the days after this treatment, dead beetles showered down onto the floor of Westminster Hall like black rain.

The treatment seemed to work: although not all the larvae were killed, enough death-watch were exterminated to slow dramatically the rot. The roof would not fall at this delicate moment. After the war, a piece of the roof was put on display at an exhibition at King’s College, London to show how close it had come to destruction. One newspaper report described the oak as looking like ‘a piece of old sponge’. A permanent solution using higher-grade pesticide finally killed off the remaining beetles in 1971. And as for Maxwell-Lefroy, he was killed by one of his own experiments in 1924 when he was engulfed in toxic gas while researching a new pesticide.

Sarah Lonsdale is the author of Rebel Women Between the Wars: Fearless Writers and Adventurers (Manchester University Press, 2020).

Source: History Today Feed