Dolphins of the Belfiore | History Today - 10 minutes read

In the mid-15th century, Ferrara was one of the most glittering cities in Renaissance Italy. Under the rule of Leonello and Borso d’Este, it had become a centre of cultural patronage and a magnet for artists throughout Europe. Whereas before, marchesi had contented themselves with a forbidding castello, a rash of fine palaces now began to spring up, each more dazzling than the last. Frescos and panel paintings were commissioned from Piero della Francesca and Rogier van der Weyden; grandiose portrait medals were struck by Pisanello; and a sumptuous manuscript of the Bible – arguably the finest in Italy – was executed by Taddeo Crivelli and his team of illuminators. The court thronged with humanists, fired with love of the antique. At the university, where the young Nicholas Copernicus would soon arrive, scholars like Teodoro Gaza revived the study of Greek; and everywhere, churches and halls resounded to the music of Pietrobono and his circle.

Yet arguably the jewel in Ferrara’s crown was the Belfiore Palace. Designed to rival the finest urban residences of the Medici, it was constructed just outside the city walls, surrounded by gardens and parkland. Even by the Este’s standards, it was exceptional. But its highlight was the studiolo (study). A deeply private space, intended for use by the signore alone, it was the encapsulation – if not the summation – of the Este’s cultural pretensions.

Having decided that he wished it to be decorated with paintings of the Muses, Leonello invited his humanist tutor, Guarino da Verona, to devise an appropriate scheme. In his reply, Guarino explained that, while some believed there were three, four, or even five Muses, the correct number was probably nine. He then went on to provide a detailed, if idiosyncratic, description of how they should all look and composed a Latin motto for each. Work began soon afterwards. The painter Angelo (del Maccagnino) da Siena – whom Guarino regarded as one of the greatest artists of his day – was commissioned to realise the design. Two years later, the first paintings were ready. From an account by Ciriaco d’Ancona, who saw them, we know that these depicted Clio (the muse of history) and Melpomene (the muse of tragedy); and, from what he says, it appears that Angelo may have been selective in his adherence to Guarino’s recommendations. While Clio was shown in exactly the way Guarino had intended, Ciriaco’s description of Melpomene bears only a passing resemblance to the original plan.

After Leonello’s death in 1450, Angelo continued work under his brother Borso, but he made little progress. According to Guarino’s pupil, Lodovico Carbone, by his death in 1470 he had not completed a single additional muse. Another artist seems to have been appointed to take his place and at least one more panel may have been added to the series. In 1459, however, a local painter, Cosimo Tura, was put in charge and it was he who completed the cycle.

The finished series was, by all accounts, a glory for the ages. According to Ciriaco, the panels by Angelo da Siena alone were remarkable. ‘I have to marvel exceedingly at this painter’s talent’, he wrote. But in 1468, during a war with Venice, the Belfiore Palace was severely damaged. Though many parts of the building were saved, including a number of 14th-century frescos, nothing more was heard of either the studiolo or its Muses.

Many scholars believe that the room was destroyed. But there is good reason to believe that at least some of the paintings survived – and are still to be found hiding in museums around the world.

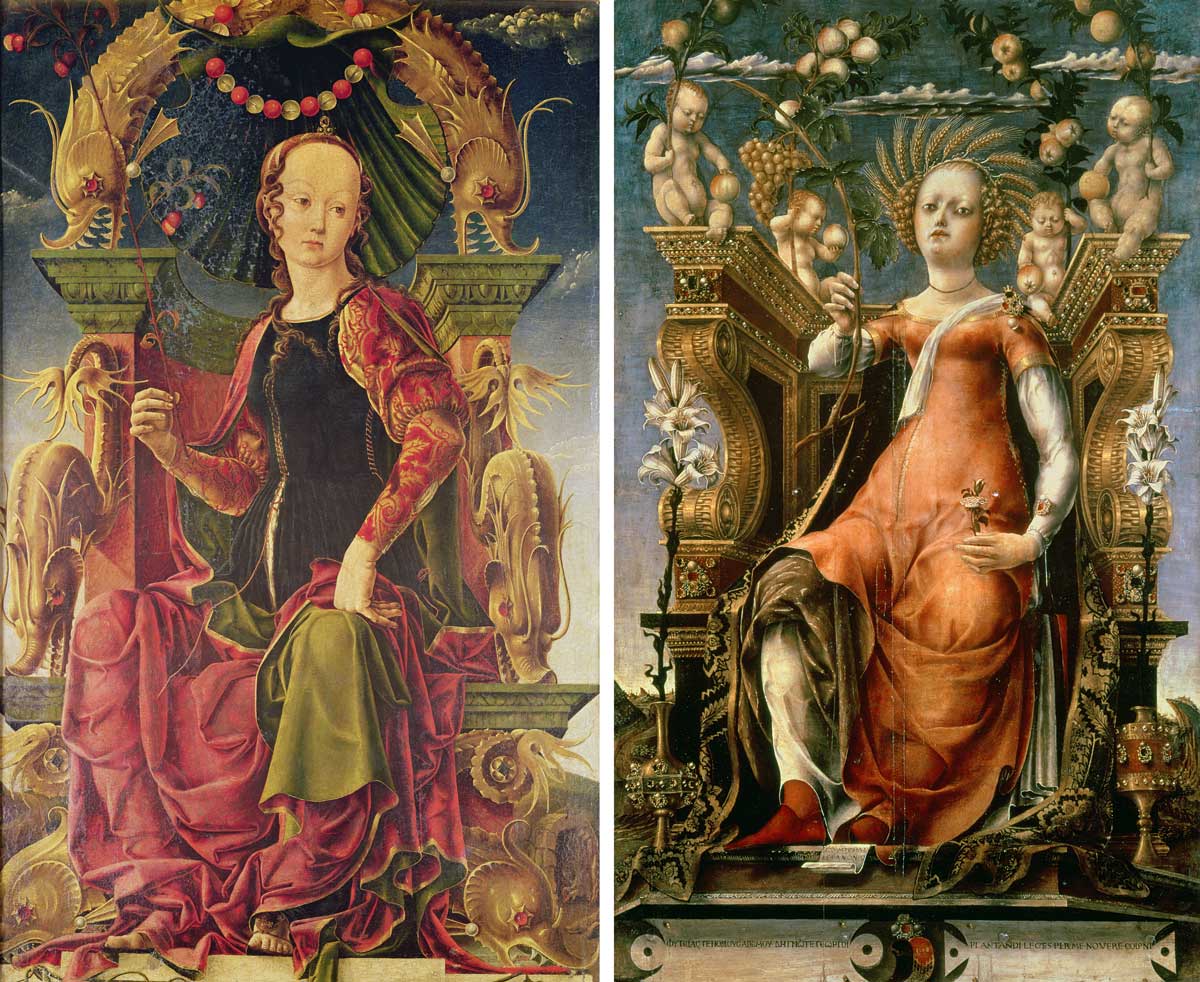

Raiders of the lost art

Where they are, however, is a puzzle. The most likely candidate is a painting once thought to represent Ceres (or Autumn) in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. As the art historian Miklos Boskovits pointed out, it is ‘virtually certain that [this] actually did belong to the Belfiore cycle’. Not only is the artist, Michele Pannonio, known to have been in Ferrara at the time the studiolo was being completed; but the depiction of a seated woman, surrounded by putti and holding flowers and fruits, corresponds neatly with Guarino’s description of Thalia, the Muse of Agriculture. Perhaps most tellingly, however, the motto Guarino devised for her can be read at the bottom of the panel in both Latin and Greek. And the prominence given to Borso d’Este’s personal symbols – the rose and the lily – can hardly be a coincidence, either.

Finding the others has proved much trickier. A number of paintings have been considered, including two allegorical figures in the Strozzi Collection in Florence and a so-called Caritas at the Museo Poldi-Pezzoli in Milan. Perhaps the most frequently proposed, however, is a panel attributed to Cosimo Tura in the National Gallery in London.

This is a remarkable work, which bears more than a passing resemblance to Pannonio’s Thalia. Not only is it of comparable size, but there are also a number of striking compositional similarities. Like the Budapest panel, it shows a slender woman with long, Crivelli-like fingers, seated on an elaborately carved throne, decorated with dolphins and topped by a scallop shell. Above her head hangs a string of glass beads; in her hand is a branch of cherries. Both paintings were intended to be seen from the same point of view – that is, from below – and they share a certain statuesque dignity. In the absence of documentation, however, one of the only ways of determining whether Tura’s painting actually came from the studiolo of Belfiore is to identify its subject.

Some scholars have argued that Tura’s painting represents Calliope, the Muse of epic poetry. But there are a number of obvious problems with this. Unlike Pannonio’s Thalia, Tura’s work doesn’t bear any relation to Guarino’s description at all. In his letter Guarino wrote that:

Calliope, the seeker out of learning and guardian of the art of poetry … provides a clear voice for the other arts; let her carry a laurel crown and have three faces composed together, since she has set forth the nature of men, heroes, and gods.

Now, it is true that, if Ciriaco d’Ancona’s account is to be believed, Angelo da Siena’s Melpomene bore only a vague similarity to Guarino’s description; so we should probably be willing to grant Tura a bit of artistic licence. But this is taking things too far.

Nor does Tura’s panel seem to have been inspired by any classical representations of Calliope. Although it is doubtful that he had seen any of the red-figure vases or mosaics on which she appears, he may have been aware of descriptions found in literary sources, perhaps through humanists at the Este court. If so, he may perhaps have known that Ovid describes her as having ‘ivy twined in her neglected hair’ (Fasti 5.79); while Statius has her carrying a lyre (Silvae, 5.3.15) and a fragment of Baccylides portrays her as ‘white armed’ (Fr. 5). But again, none of these are found in the painting.

Most importantly, Tura also included a lot of additional features, which do not appear in any depiction of Calliope: two small images of a pilgrim-like figure and a blacksmith next to her throne, the scallop shell above her head, and – of course – the dolphins.

A variety of explanations for these attributes have been put forward. The sound of the blacksmith’s hammer as he beats it on the anvil may, for example, evoke the resonance of poetry when inspired by the Muse; the scallop shell, like the elaborate throne, could be a visual allegory of poetic invention; and the dolphins may refer to an association between the Muses and the Sirens. But these explanations are doubtful at best and only account for a few of Tura’s additions.

Mighty Aphrodite

If Tura’s painting does not depict Calliope, who does it represent? One theory, suggested by Anna Eörsi, is that it shows Erato, the Muse of erotic verse. But this has all the same weaknesses as Calliope. Another notion, favoured by Tim Shepherd, is that the subject is Euterpe, the Muse of lyric poetry. This is at least partly supported by X-ray analysis, which has revealed that the back of the throne originally looked a bit like the pipes of an organ (which Guarino mentioned in his letter), and by the contemporary association between music and a blacksmith’s hammer. However, it fails to account for the pilgrim – and uses an equally shaky connection with the Sirens to explain the dolphins.

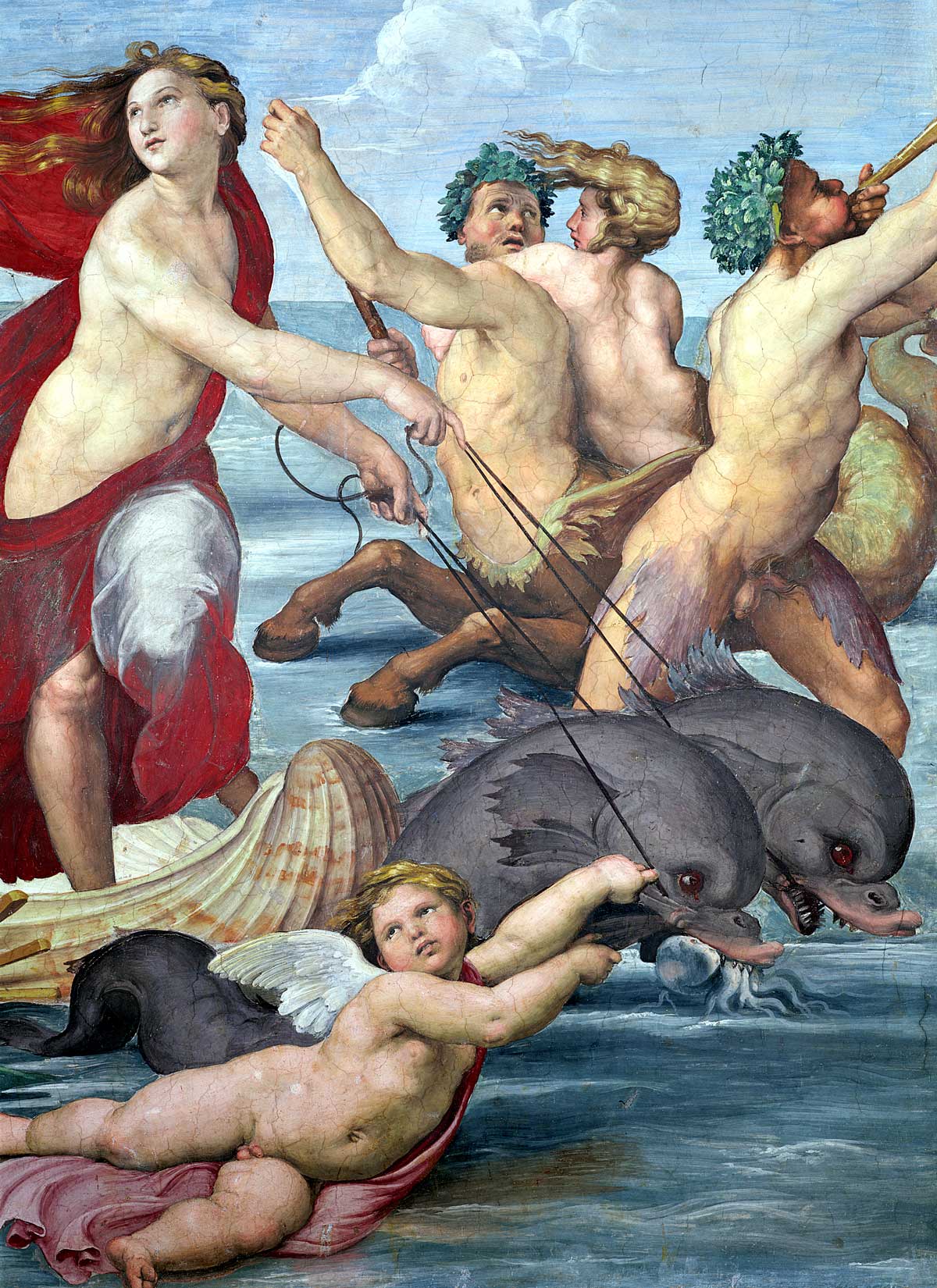

Who is it, then? Happily, the dolphins may provide a clue. True, they don’t look much like the intelligent creatures we are familiar with today. With their sharp teeth, spiny fins and ruby-red eyes they actually look rather frightening. But they aren’t all that unusual by the standards of the Renaissance, as you can see if you look at Raphael’s Triumph of Galatea of 1506, now in Rome’s Villa Farnesia. Importantly, in classical mythology, dolphins are associated directly with only a small handful of figures including Amphitrite and Galatea. Perhaps the most intriguing is, however, Aphrodite. According to the Greek poet Hesiod, she had sprung from the foam produced when Uranus’ severed genitals were thrown into the sea. Her sacred animals were the sparrow, the dove, the swan, the swallow and the iynx; but, because of her origins, she retained a close connection with the sea and often appeared in classical art accompanied by dolphins. Some of the more striking examples include the Venus Mosaic at Kingscote in Gloucestershire and a mosaic showing her birth from Zeugma, now in the Gaziantep Museum of Archaeology in Turkey.

If Tura’s figure is of Venus, it would explain why he included so many other strange features. As can be seen in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, the scallop shell was one of Venus’ major attributes. The blacksmith can be identified with her husband, Hephaestus, whose principal attributes were the hammer and anvil; and the ‘pilgrim’ is most likely her lover, Hermes, the messenger of the gods, who is often shown with a cloak and herald’s wand. Meanwhile, the red fruits evoke her association with fertility and desire.

Be like the dolphin

Of course, there is no mention of a Venus either in Guarino’s letter or in any of the other documents relating to the Belfiore studiolo. The natural conclusion, therefore, is that it must have been intended for somewhere else – either in Ferrara, or further afield. But there is another possibility. Although Venus was most definitely not a Muse, there were indications in some classical texts (such as Lucretius’ De rerum natura) that she could be associated with them. Such was, perhaps, only to be expected. After all, as the goddess of love she was a source of poetic inspiration – and therefore, perhaps, their natural counterpart.

This is not to say that Tura’s painting was intended to function as a ‘tenth woman’ in the Belfiore cycle, but nor can we exclude the possibility that a Venus may have played some role in the scheme of Leonello’s studiolo. Given the similarities in size and design between Tura’s panel and Pannonio’s Thalia, and the fact that Guarino’s letter was clearly not prescriptive, it is conceivable that the nine Muses were only part of the study’s decoration and that other (allied or analogous) figures were also included.

This is just speculation. But mysteries are always fraught with uncertainty and conjecture. The important thing is to be like the dolphin and dive right in.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, is now available in paperback.

Source: History Today Feed