Benjamin Banneker’s Broods of Cicadas - 11 minutes read

In the spring of 1749 Benjamin Banneker – the 17-year-old son of a freed slave – thought the world was about to be eaten whole. While working on his family’s farm in Oella, Maryland, he saw ‘thousands of locusts’ suddenly rise up from the ground and ‘creep …up the trees and bushes’, as if directed by some unseen hand. Fearing that they had come to ‘eat and destroy the fruit of the Earth, and would occasion a famine in the land’, he set about killing them as quickly as he could. But he soon realised it was pointless. There were just too many of them. Helpless, he waited with trepidation for the destruction to begin. Yet it never came and within a matter of weeks the ‘locusts’ had vanished without trace.

What Banneker thought were ‘locusts’ turned out to be a species of periodical cicadas (Magicicada) and what he had seen was just one of several gigantic ‘broods’ native to North America (Brood X). Like their European counterparts, periodical cicadas spend the vast majority of their lives underground as immature nymphs. Secreted in burrows, they feed off the xylem found in roots and generally don’t cause any bother. Once every 13 or 17 years (depending on the brood), when the temperature of the soil is just right – usually in late April or May – they clamber upwards en masse. When they reach the surface, they shed their outer skin and assume their adult, winged, form. The mating ritual then begins. Gathering together in ‘choruses’, the males make a high-pitched clicking sound to attract females; and for the next few weeks they reproduce with proverbial enthusiasm. Yet as soon as they have laid their eggs in the bark of trees they die, leaving their young to hide until the next great awakening.

Banneker was not the first person to see periodical cicadas in North America, of course. Sightings had been reported in 1633 [1634], 1666 and 1675, and brief descriptions of the insect’s life cycle had been published by Andreas Sandel and the botanist John Bartram in 1715 and 1737. Nor was Banneker the only person to remark on the 1749 emergence. Peter Kalm, a Swedish naturalist, witnessed the same brood while visiting Pennsylvania. He, too, would write a study of the cicada’s habits, albeit hedged about with caveats. But Banneker’s encounter was nevertheless to prove vital to our understanding of the cicada’s periodicity – and would mark the beginning of one of the most remarkable, if overlooked, scientific careers of the American Enlightenment.

Auspicious return

Banneker was born on 9 November 1731, the son of Robert and Mary Bannaka (or Bannaky). In surviving documents, Mary is described as a ‘free black’, and is most likely to have been the daughter of a black slave and a white indentured servant. Robert, by contrast, was a freed slave. Like so many others, he had been taken from Guinea and forcibly transported to Maryland to work on the tobacco plantations that were the mainstay of the colonial economy. How long he was kept in this condition is unclear, but he was fortunate to be granted his freedom just before the British authorities introduced measures to prevent slave-owners from manumitting their slaves without the legislature’s permission.

Despite Robert and Mary’s background, the Bannekers were moderately prosperous. In 1737, when Benjamin was six, his father purchased 100 acres of land in exchange for 7,000 lbs of tobacco and the family built a small log cabin, which stands to this day. Benjamin received little formal education. He is likely to have learned the rudiments of reading and writing from his grandmother, Molly Welsh; but whether he went on to attend a local school is unclear. If he did, it cannot have been for long.

Benjamin had a hunger for learning, though. Anything to do with the natural world fascinated him and his encounter with the cicadas in 1749 seems to have been instrumental in persuading him to cultivate his interest seriously. Judging by his later account, his scientific instincts were already well developed. He not only had a keen eye, but also formulated a sensible (if mistaken) hypothesis about the cicadas’ environmental impact. He even appears to have suspected that their immense numbers were key to their survival. Most tellingly, he also made a mental note not to forget what he had seen and to determine by observation when they would return.

From that moment on, patterns and periodicity would be an abiding preoccupation. Four years later, he tried his hand at clock-making. Captivated by the rapid pace of technological change, or – more likely – drawn to the oft-cited analogy between watchmaking and the workings of nature, he built a wooden clock of his own by copying the mechanism of a pocket watch he borrowed from a wealthy friend. For a young man with little, if any, experience of timepieces, it was nothing short of remarkable.

His learning was, at this stage, very much of a practical bent. Driven by curiosity, he proceeded by trial and error whenever he had a free moment. By necessity, his progress was halting and uncertain – more so after his father’s death in 1759 obliged him to assume responsibility as head of the household. But his enquiring mind continued to whir and, when the cicadas returned in 1766, he was no longer the wide-eyed naïf of 17 years before. This time he ‘had more sense than to endeavour to destroy them, knowing they were not so pernicious to the fruit of the Earth as I did imagine they would be’. And, being less afraid, he was able to observe them closely – more closely, in fact, than many other scientists who witnessed their appearance at the same time. For, while they were generally content to study a single resurgence and guess at their periodicity on the basis of hearsay, Banneker seems already to have realised that the only way to establish the length of their cycle for certain was to watch them over a much longer period.

The cicadas’ return proved auspicious. Six years after he watched them rise up in clouds from the ground, three brothers – Andrew, John, and Joseph Ellicott – bought some land not far from Banneker’s farm. Unlike most Marylanders, who were Catholic, the Ellicotts were Quakers and had little time for racial prejudices. They quickly struck up a friendship with their neighbour and, on learning that Banneker shared their passion for science, gladly lent him books with which to further his studies.

Calculating cicadas

Little is known of Banneker’s life in the following decades. Nothing has survived to indicate how he was affected by the Revolutionary War. But by the time the cicadas came back for a third time in 1783, just a few months before the conflict ended, Banneker had made striking progress in all his studies – and was well placed to capitalise on his talents under the new Republic. Some five years later he began studying astronomy intensively and was sufficiently skilled in mathematics that he could calculate the tides and a host of other phenomena.

In spring 1791 Major Andrew Ellicott – the son of Banneker’s neighbour, Joseph – was asked by Thomas Jefferson, then the Secretary of State, to survey the area earmarked for the new federal capital and he immediately invited Banneker to join his team. The extent of Banneker’s contribution to this project has, admittedly, been much debated. The evidence is ambiguous at best. But whatever his role, the mere fact of his involvement is eloquent testimony to the esteem in which his learning was beginning to be held.

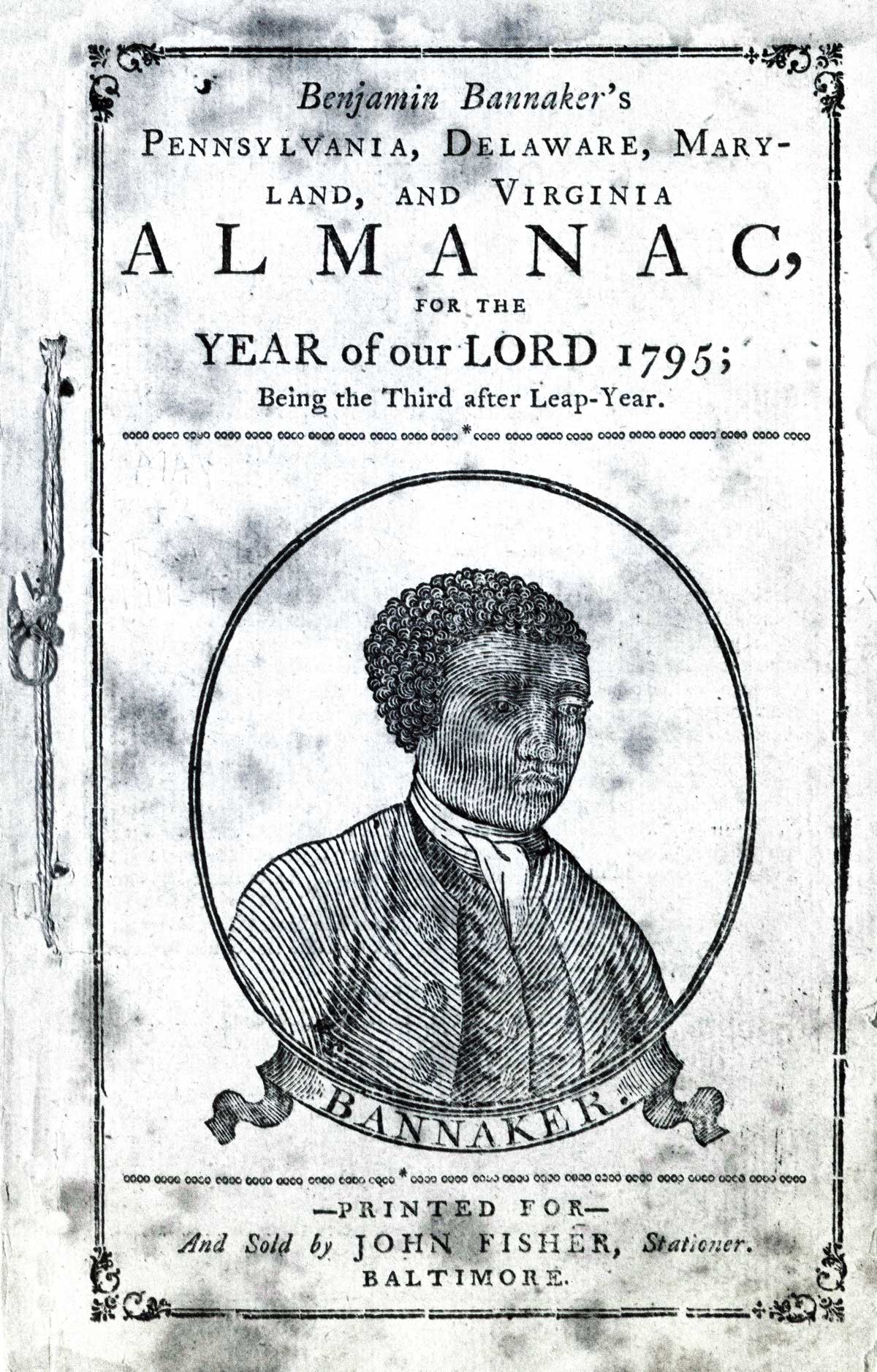

After leaving the surveying expedition, Banneker concentrated on preparing an almanac and ephemeris for the year 1792. This contained exhaustive tables detailing ‘the Motions of the Sun and Moon, the … Aspects of the Planets, the Rising and Setting of the Sun … Age of the Moon … Conjunctions, Eclipses, Judgement of the Weather’ and countless other wonders, all calculated by hand, using a series of self-derived (and remarkably complex) formulae. He showed this to his old friend Andrew Ellicott, who was so impressed that he sent it to James Pemberton, the president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. Pemberton had it checked by an astronomer and, on being assured of its ‘extraordinary’ accuracy, arranged for it to be published. It met with immediate success – so much so that Banneker prepared several more editions in the years which followed.

At about the same time, Banneker also became committed to securing justice for African Americans. Perhaps encouraged by the Ellicotts, he wrote a letter to Thomas Jefferson, who, in addition to being the Secretary of State, was also compromised by his involvement in the slave trade. Though he repeatedly condemned the institution of slavery, and once boasted that he wanted his slaves always to be well treated, he did not hesitate to order violent floggings and fathered six children by a slave girl. Much to Banneker’s chagrin, he also viewed slaves as being of inferior intelligence – although whether this was due to nature or nurture, he could not say. Banneker forcefully took Jefferson to task for his hypocrisy. Vilifying the Secretary for ‘detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression’, he demanded radical change.

Jefferson’s reply was courteous, if evasive. Perhaps stung by Banneker’s criticisms, he confined himself to vague wishes for some improvement in slaves’ living conditions. Later that same day, however, he sent a copy of Banneker’s almanac to the Marquis de Condorcet, accompanied by a note extolling his mathematical genius and hoping that such ‘eminence’ would be ‘so multiplied as to prove’ the intellectual equality of all men.

Rising again

Astronomy and mathematics remained Banneker’s principal interests, however, and he did not hesitate to bring them to bear on his study of the cicadas. At some point around the time he wrote to Jefferson, he compiled all the data he had so far accumulated in a note, inscribed in his ‘Astronomical Journal’. It was not long, but it was as detailed and comprehensive an account as anyone had yet written and represented the fruits of almost 50 years of study. Most important of all, it also included a prediction. Rejecting the hearsay and supposition favoured by most other scientists in favour of his past observations, he wrote that:

They may be expected again in the year 1800, which is Seventeen years since their last appearance to me. So that if I may venture So to express it, their periodical return is Seventeen years, but they, like the Comets, make but a short stay with us … [Yet] if their lives are Short, they are merry, they begin to Sing of make a noise from the first they come out of the Earth till they die.

Soon proved right, Banneker’s prediction was of huge value. It established beyond doubt that Brood X followed a 17-year cycle and allowed farmers throughout the eastern United States to prepare appropriately, saving needless effort and no end of worry.

Seduced by the music of the stars as much as by the singing of cicadas, Banneker continued searching for patterns in nature until his death, nine years later, at the age of 78. Many of his papers were lost in a fire shortly afterwards; and, in the decades which followed, his work was largely overlooked. Thankfully, the record has recently begun to be set right, but there is still a long way to go. Given that Brood X returned only a few weeks ago – just as Banneker suggested it would – this is the perfect time to give this most remarkable of men the recognition he deserves as a pioneer of American science and justice.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, is now available in paperback.

Source: History Today Feed