Hotel Days | History Today - 5 minutes read

As a historian who is also a consummate consumer of thrift-shop clothes, I cannot resist identifying a lurking similarity that brings the two activities together; keep wearing your worn corduroy jacket and it will come back into fashion, one hopes; carry on investigating Britain’s imperial meddling in the Middle East and people will find it relevant once again. Anniversaries, like visits to second-hand stores, provide the perfect excuse to reminisce about that which has long gone and the recent centenary of the Cairo Conference is no exception.

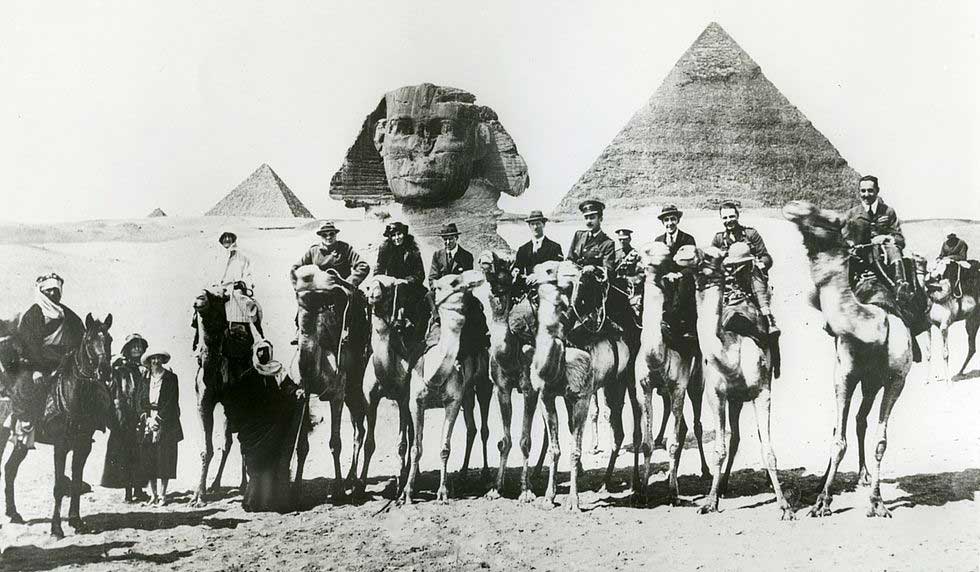

Summoned in March 1921 by Winston Churchill, eager to promote his reputation as a newly appointed Secretary of State for the Colonies, it brought together some of the more eccentric to flamboyant members of Britain’s ruling elite, including T.E. Lawrence, Field Marshal Edmund Allenby and Gertrude Bell. For ten days, they rubbed shoulders in the luxurious Semiramis Hotel and redrew the map of the post Ottoman Middle East, effectively creating modern Iraq and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

C. Brad Faught has produced a highly readable re-enactment of those diplomatic negotiations that is not short of gusto and dense atmosphere. The 30-plus men and single woman who assembled in Cairo were confronted with a knotty situation due to Britain’s erratic wartime diplomacy. Carving out a new geostrategic order, they believed they could reconcile not only the promises given to Hussein bin Ali and the Zionists, but also avoid discord with the French over the implementation of the Sykes Picot Agreement. The ‘Sharifian Solution’ – an ambitious plan to install Sharif Hussein’s sons as rulers of new states in Mesopotamia and Syria, first proposed by Lawrence but modified by Churchill – was their attempt to square the circle. Contrary to the standard view of empire-building and nation-building as two incompatible political projects, Faught’s book makes a convincing case that implicit in Churchill’s prioritising of Britain’s strategic position was ‘a recognition that a certain degree of local nationalism was necessary – even welcome – lubricant in finding the right calibration for turning the imperial wheel’. Less convincing, however, is the logic leading Faught to deduce that, in hindsight, Cairo’s ‘regional blueprint’ also propelled ‘a kind of flow-through phenomenon’ culminating in decolonisation and independence.

A second point on which Faught diverges from previous accounts of the conference is in his insistence that Churchill, who was pressured to reduce Britain’s expenditures in Mesopotamia, was not motivated by economic considerations alone, but guided by a gradualist, though paternalistic, conception of the role of the Empire in an age of nationalism: Empire was to protect the groups that resided under its wings and tutor them towards self-realisation. This apologia pro-imperii is amended by the author’s acknowledgement of several prejudices built into the foundations of this kind of statecraft, but the ultimate verdict remains favourable to the western architects. Even when it comes to a thorny issue such as the growing animus between Jewish and Arab nationalists in Palestine, Faught maintains that ‘in Churchill’s inimitable way he had sounded the trumpet of modern pluralistic nationalism, but also a specific new nationality, that of the “Palestinian”, shorn of its historically exclusive Arab identity and infused with what he believed would be undoubted “benefits of Zionism”’. If Churchill and his peers are to be judged harshly, the book’s conclusion suggests, it should not be for engaging in Machiavellian realpolitik as much as for being callow idealists bewitched by western political values, incapable of comprehending that the breakdown of traditional hierarchical and tribal society would prepare the ground for fervid mass nationalism.

A seasoned storyteller, Faught is enthralled by his larger-than-life imperial heroes. As often is the case with imperial histories, however, he stubbornly insists on telling the story from the vantage point of the British actors, who are ultimately the only fleshed-out characters. What explains the profoundly anti-climactic sense of betrayal felt by many local leaders remains inexplicable, a conundrum. Courageous experiments made independently by liberal Syrians who sought to create their own representative constitutional state under the aegis of Faisal bin Hussein, retold brilliantly by Elizabeth Thompson, are left outside the discussion. The incentives and motivations of the local brokers who supported the British, and were essential for implementing their grandiose plans, remain equally abstruse and opaque. Why should Ja’far Pasha al-Askari, a decorated Ottoman general who fought the British and was captured by them, suddenly switch sides and become so intimately involved in the accession of Faisal in Iraq, vetting out alternative candidates? What was it that made the Baghdadi-Jewish impresario Sassoon Eskell so excitedly pro-British? In what sense were there ‘Iraqi nationalists’ in 1921? What new opportunities had opened to them with the British occupation, and to what extent did Britain rely on pre-existing local arbitrators and intercessors in executing its schemes?

These questions are still awaiting their answers, but they probably demand different storytelling. One that will not revisit the all too ostentatious Semiramis Hotel alone but dare to look into the backstreets and explore the expanse behind the glamorous building. After all, even Lawrence, feeling disgusted, reported to his mother that the hotel was ‘a horrible place: makes me Bolshevik’.

Cairo 1921: Ten Days that Made the Middle East

C. Brad Faught

Yale University Press 251pp £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Arie M. Dubnov teaches history at the George Washington University and is co-editor of Partitions: A Transnational History of Twentieth-Century Territorial Separatism (Stanford University Press, 2019).

Source: History Today Feed