A Cure Worse than Disease - 5 minutes read

Quarantine as a means of preventing the spread of disease is an ancient phenomenon. Early forms of the practice are described in the Old Testament book of Leviticus and in the writings of Hippocrates. The word itself is Venetian, derived from the quaranta giorni (40 days) that arriving ships were expected to anchor outside La Serenissima to ensure freedom from the plague.

Unlike isolation, quarantine focuses on the segregation of the potentially ill, rather than those exhibiting symptoms. Voluntary exclusion is the common response to the former today. More forceful measures have, throughout history, been the normal prescription for the latter. The Derbyshire town of Eyam, which voluntarily isolated itself during the plague outbreak of 1666, is a brave outlier.

Despite the name, the length of time required in quarantine or isolation can vary widely, from hours in the case of substances like anthrax, to effective lifetime exile for those suffering with leprosy. Yet if the ways and means are different, there are discernible patterns in how quarantines have disproportionately and often discriminatorily impacted on particular communities – in particular the poor and the alien.

A good indication of the long relationship between quarantine and xenophobia can be found in the US at the turn of the 20th century.

In 1892, the SS Massilia docked in New York City with a cargo of immigrants, predominantly Russian Jews. Within a month, those who had disembarked were rounded up and charged with having brought typhus to the city.

What distinguished this initiative from those that became widespread in Europe during the Middle Ages was the timing and geography of its enactment. Whereas before the practice had mostly applied to sailors seeking to enter a port at the moment they sought to enter it, New York authorities now forcibly removed and actively displaced those immigrants, healthy or otherwise, who had arrived in the city on the Massilia to North Brother Island. There they were presented with inadequate medical care to go with food and funeral services that violated Jewish law. This was more a refuse heap than a hospital.

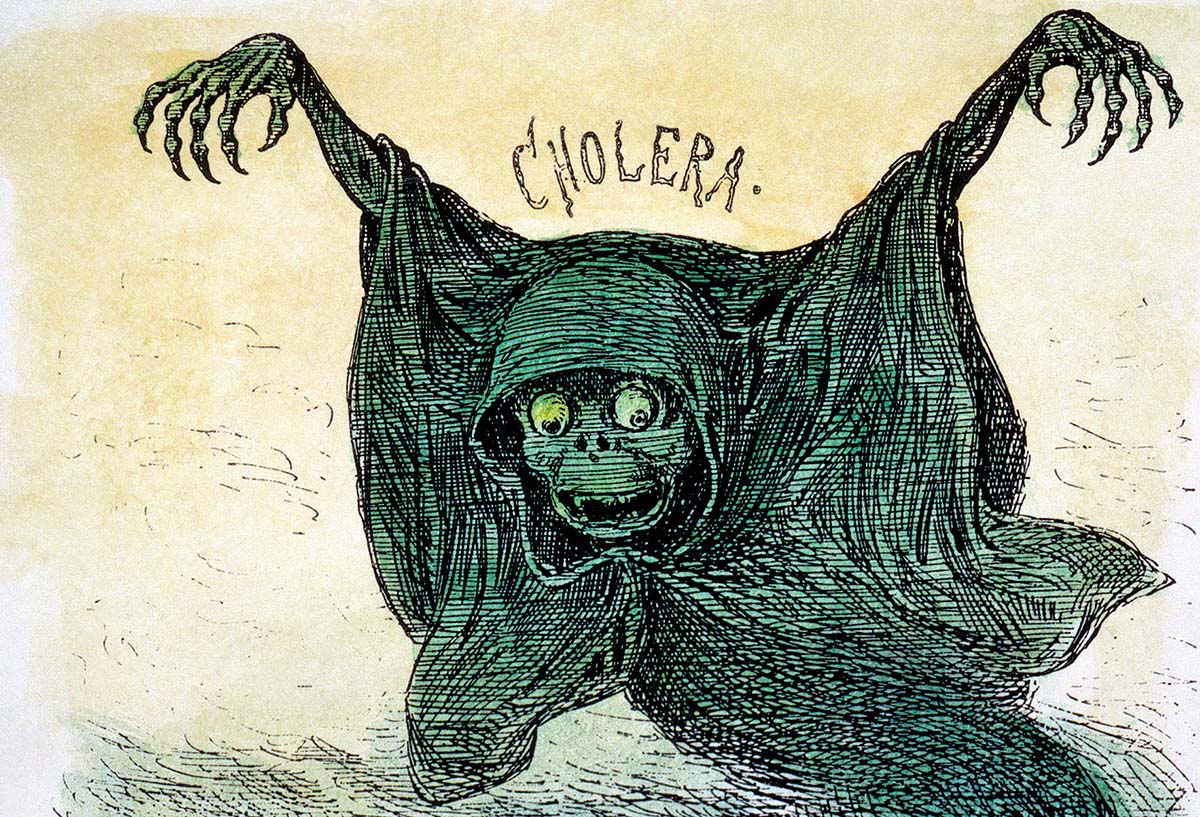

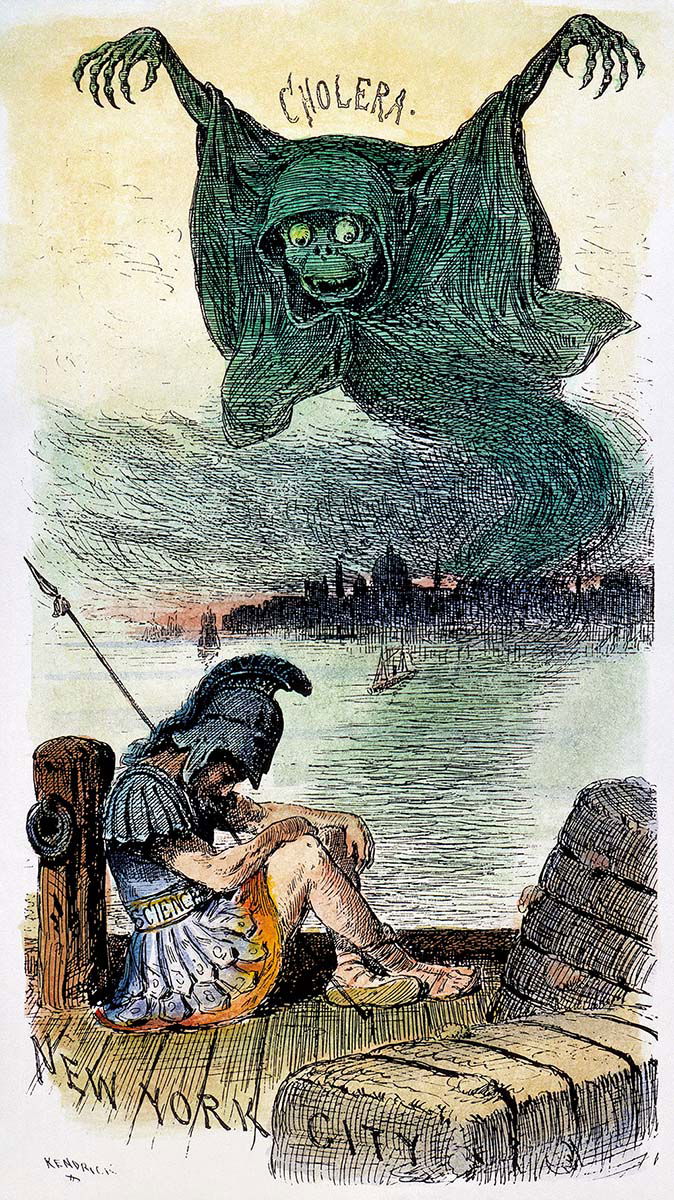

When the typhus outbreak died down, the approach was considered vindicated by press and public alike and, when cholera broke out that summer, the practice was reintroduced. Again, discrimination was rife. As had been the case with the typhus roundups, only steerage-class passengers, of whom many were Jews, were detained on disembarking at the Port of New York.

Leaving aside the debate around the efficacy of the approach, it seems evident that straightforward bigotry and xenophobia mingled with more reasoned concerns about disease prevention. In doing so they produced quarantines that were crueller and more callous than they either needed to be or would have been had the disease affected a white ‘native’ community.

The zeitgeist was not one of sympathy for the poor and the immigrants who suffered from cholera, but on portraying those who stepped off the boats as little more than vessels for disease themselves. Senator William E. Chandler exemplified the lack of sympathy, levelling the charge that Russian Jews ‘introduce disease and jeopardise the health and lives of respectable Americans by introducing forms of sickness not indigenous to the soil by reason of our cleanly habits’. Combined with his attempts in 1893 to ban not just Jewish but all immigration as a panacea to the ‘public health evils of immigration’, Chandler is emblematic of the nativist response to disease control. However, his views also reflect a mistrust common to both the public and political classes.

A letter to Chandler from Sarah Gaylord of Springfield praises his stance, adding: ‘We don’t need any more … dirty low lived creatures breeding all kinds of diseases. We have the Negroes and the Indians to take care of that.’ For many, society was two tiered, with clean natives under threat from dirty, diseased immigrants.

The conflation of public health and immigration has not gone unchallenged. As early as 1893 in the US, immediately after the cholera quarantines, Congressman Bourke Cockran, himself an immigrant from Ireland, explicitly sought to delineate the two, arguing that ‘for one hundred years the immigration to this country has continued without any of the dangers of evil consequences’. Neither Cockran’s intervention, however, nor the passing of the 1893 Quarantine Act that made implementation more uniform, stopped the quarantining of Chinese workers in San Francisco in 1900. This was deemed to be discrimination and in violation of the 14th Amendment, which grants equal protection to any person tried under US jurisdiction, but the ruling came too late for the workers who had lost their jobs, been separated from their families or undergone forced inoculation. Compared with the response to the plague outbreak in Hawaii in January 1900, the response might even have seemed measured; San Francisco at least did not see the type of ‘controlled’ fires that accidentally destroyed 4,000 homes in Honolulu’s Chinatown.

Even though the ruling acknowledged that there was no evidence that Asiatic communities were more at risk, the ongoing perception of undesirability associated with them cannot have been immaterial to the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1902, which barred all immigration from China.

Nor is the 21st century exempt. It was only in 2009 that President Obama lifted the 22-year ban on HIV-positive individuals entering the US. More recently still, in response to the 2018 migrant caravan that moved towards the US border with Mexico, the Fox News host Tomi Lahren called for a hard border to keep disease out, asking her audience whether they wanted ‘TB, HIV/AIDS, chicken pox, or hepatitis in your communities and your children’s schools’.

As Wuhan’s residents face restrictions on travel and potential loss of income, the complex balancing of public health and individual liberty is as challenging as ever.

Edward Willis is a freelance writer.