A House Divided | History Today - 5 minutes read

Shortly after 10am on Sunday 4 April 1920, a cinematographer set up his camera near the entrance to the Christian suq inside Jerusalem’s walled Old City to film Muslim pilgrims gathering near the Jaffa Gate at the start of the festival of Nebi Musa. According to local legend, the 12th-century Muslim leader Saladin invented Nebi Musa to thwart any attempt by Christian pilgrims pouring into Jerusalem at Easter to reclaim it for Christendom. Elsewhere in the Holy City, Christians were celebrating Easter and Jews were preparing for Passover. The mood of the crowd at the Jaffa Gate was cheerful at first but, as the film shot by the unknown cameraman shows, violence suddenly broke out and the crowd scattered. It is impossible to tell exactly who was attacking whom, but the film captures the very moment when Jerusalem was plunged into a frenzy of anti-Jewish rioting that lasted four days.

The underlying cause of this first major crisis for Palestine’s new British rulers was the anger which Palestinian Arabs, Christian as well as Muslim, felt over the British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour’s pledge, in November 1917, of British support for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. They saw that what Balfour really meant entailed the creation of a Jewish state and, ultimately, their own dispossession. Coupled with their opposition to Zionism was their enthusiasm for Emir Feisal, the field commander of the Hashemite army which the British had financed, trained and equipped from 1916 to 1918 to fight the Ottoman Turks and who, since the end of the First World War, had been the de facto ruler of Damascus. To his followers, Feisal represented both a rallying point against British and French plans to carve up the Middle East and their best hope for an independent state comprising the defunct Ottoman Empire’s Arab provinces, including Palestine. It was no mere coincidence that, just before the rioting in Jerusalem began, speakers addressing the Nebi Musa pilgrims prominently displayed Feisal’s portrait.

Ultimate responsibility for maintaining public security in Palestine lay with the British Army, but the day-to-day business of government was handled by the Occupied Enemy Territories Administration (South), or OETA, which General Sir Edmund Allenby created six months after his British imperial army captured Jerusalem in December 1917. The OETA dedicated itself to maintaining the status quo in Palestine in line with the Laws and Usages of War, as set down in the 1907 Hague Convention, until such time Great Britain signed a peace treaty with Turkey that would pave the way for an implementation of the Balfour Declaration. To this end, it did not allow itself to publish the full text of the Declaration. Zionists came to regard this and other decisions by the OETA as proof of an ingrained antisemitism. Those among them with first-hand experience of the way that Tsarist chinovniki used to orchestrate pogroms in pre-revolutionary Russia convinced themselves that the OETA itself was behind the rising tide of Arab anti-Zionist agitation. In turn, Zionists were accused of creating a parallel administration in Palestine and, even worse, of importing Bolshevism from the newly founded Soviet Union. These spats cost several OETA officials their jobs. By Easter 1920, relations between the British authorities in Palestine and local Zionist leaders were tense.

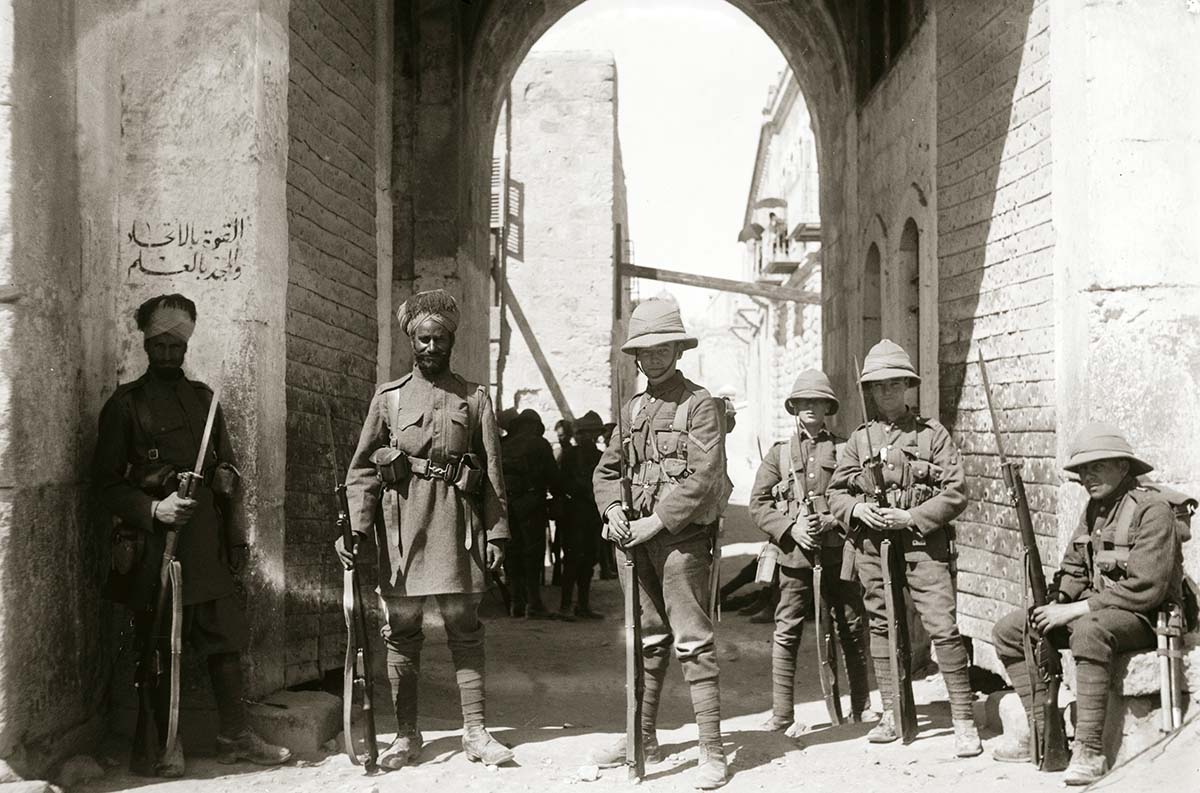

The political situation in Palestine was worsening. There had been two big anti-Zionist demonstrations in Jerusalem, but these passed with little trouble. In Palestine’s remote northern fringes, however, Syrian Druze tribesmen attacked a Jewish colony, killing six of its members. In Jerusalem, Jewish veterans who had fought in Palestine under Allenby during the Great War and local members of the Maccabi Zionist sports association combined to form self-defence squads to meet the threat of anti-Jewish violence. One of their organisers was Vladimir Jabotinsky, ex British Army lieutenant, proud holder of the Military Cross and an especially pugnacious and forthright Zionist. Nevertheless, Jerusalem’s military governor, Colonel Ronald Storrs, was not unduly alarmed by these troubling portents. On paper, he had at his disposal three infantry battalions, one British, two Indian, in case the Nebi Musa festivities erupted into violence, but he did not ask the army to place them on standby. Instead, Storrs left Jerusalem’s police force of eight officers and 188 constables, mostly locals, in sole charge of public security. It was reported that the first he knew that anything untoward was happening occurred at the precise moment somebody burst into St George’s Anglican Cathedral outside the Old City, where he and the rest of Jerusalem’s British community were celebrating Easter, and yelled: ‘They’re killing each other out there!’

Despite the swift imposition of martial law, five Jews and four Arabs were killed, 242 people injured and dozens of Jewish properties looted and vandalised before British troops were able to restore order. Storrs compounded his earlier misjudgement over the level of policing required for the Nebi Musa festival by ordering the arrest of Jabotinsky and 19 of his comrades for possessing weapons and ammunition. News of the Jerusalem ‘disturbances’ and the 15-year prison sentence handed to Jabotinsky by a military tribunal were met with fury by Zionists and their allies in the British Parliament and press. The OETA now stood accused of organising a pogrom. The British authorities in Jerusalem acted quickly to quell the uproar by reducing Jabotinsky’s jail sentence to one year, but to head off a major breach with the Zionist movement, Prime Minster David Lloyd George ordered OETA’s replacement with a civilian administration headed by a high commissioner who would uphold the Balfour Declaration. The regime change occurred well in advance of Great Britain signing a peace treaty with Turkey and being awarded a mandate to govern Palestine by the League of Nations. On such shaky political and legal foundations did British rule in this thrice-promised land go forward.

James Barker is a freelance film researcher and is currently writing a book about Britain and Palestine 1799-1917.