Trust in Change | History Today - 9 minutes read

A leader in the Daily Telegraph, published on 25 September and headlined ‘The National Trust needs to drop its woke nonsense’, propounded a series of theses about what the National Trust, the charity for heritage conversation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, exists to do (Scotland has a separate organisation). The job of the Trust, which has 5.6 million members and an annual income in excess of £630 million, ‘is to conserve, not comment’, was one thesis. But to conserve what? Things that ‘the nation holds dear’. Which nation? Well, the present one, or at least the Daily Telegraph’s idea of the present nation, which it thinks it understands pretty well, at least at a very high level of abstraction: ‘Most people’ value the National Trust’s sites out of a ‘love of place and character’. But then it appears that there are other stakeholders to be regarded. The Trust should not be casting aspersions on ‘the historical reputation of properties’ in a way that ‘breaks faith with the families that donated them’. So pointing out these properties’ associations with, for example, slavery, colonialism or homosexuality is out of bounds, because it ‘breaks faith’ with donors, regardless of whether the nation today might be interested in those things.

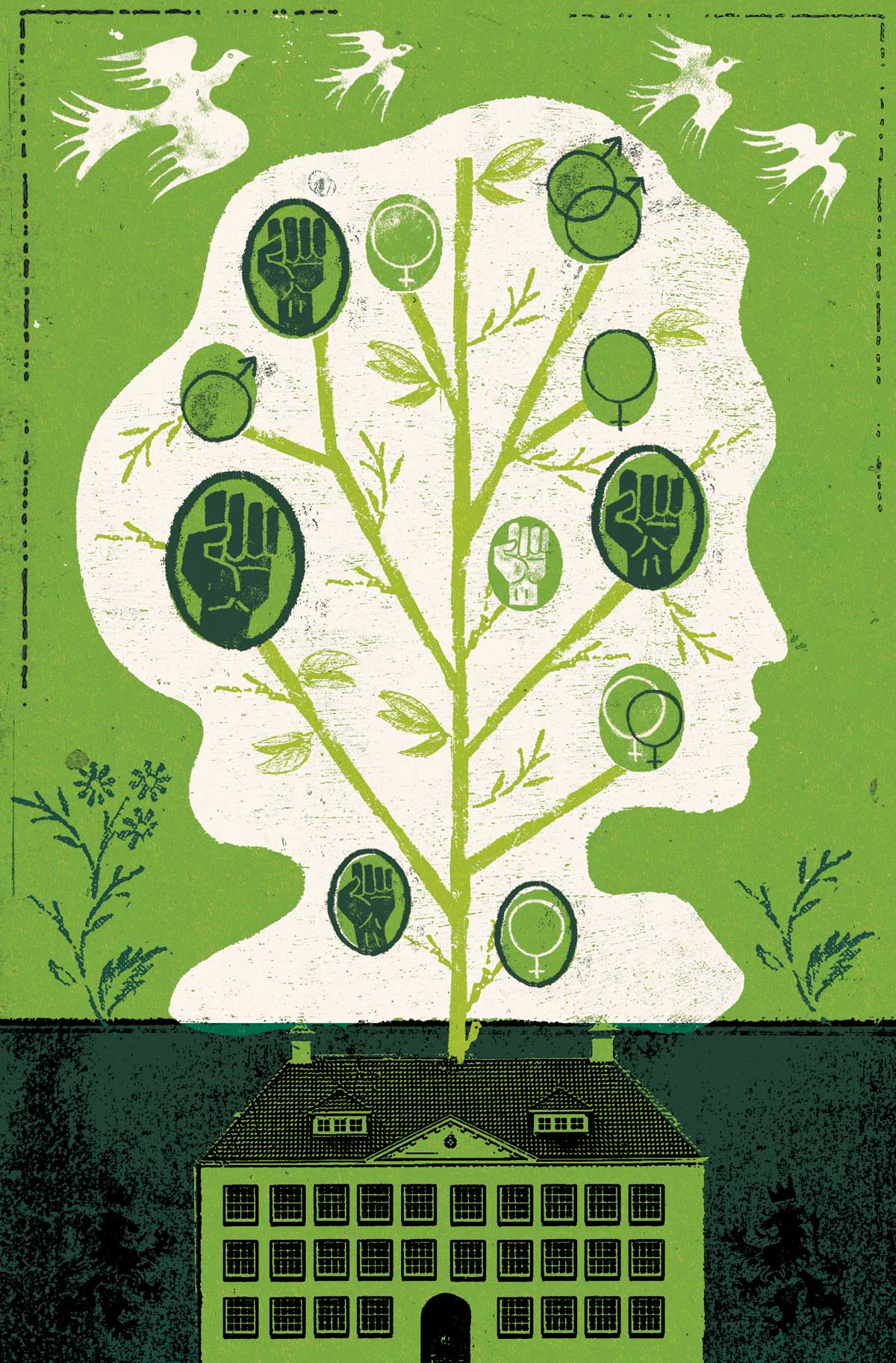

Frozen in time

This bundle of contentions about the right conduct of a heritage organisation betrays some of the same confusions that attended the recent debate about reinterpreting, pulling down (or putting up) statues. It seems to want to freeze our understanding of history at a particular point in time. On the face of it, that seems commonsensical for a ‘conservation’ or ‘preservation’ charity: what is being conserved or preserved if not something fragile from the past that might otherwise be lost? That is indeed why the UK has a listing system that identifies which buildings cannot (at least not easily) be demolished or allowed to fall into disrepair. The statue in Bristol of the slave trader Edward Colston, which was pulled down and thrown into the River Avon on 7 June 2020, was in fact listed as far back as 1977. But the listing system provides only a fairly basic form of preservation. It identifies structures that can’t be radically altered or destroyed. It says little or nothing about how they should be used, subsequent to their initial use, and nothing at all about how they should be interpreted.

Those things change all the time. The basic structure remains intact; but its context, its meaning, its ‘spirit’ changes as it passes through time and is used and interpreted by subsequent generations. That is why parties in Bristol had been seeking, at least since the 1990s, to reinterpret Colston’s statue with additional wording that would acknowledge his role in the slave trade; it was the repeated frustration of such efforts, especially in 2018-19, that led in the moment of Black Lives Matter to the targeting and subsequent toppling of the statue by protesters.

The Telegraph leader seems to appreciate this, at least to the extent of acknowledging both the intentions of the donors and the particular ‘historical reputation’ that they attached to their properties, as well as the qualities of ‘place and character’ that the nation today attaches to those same properties. But it does not follow through on this line of argument. What happens when the intentions of the donors and the values of the present-day nation conflict? At which point in time should the ‘historical reputation’ of a property be frozen? Must we feel for all time as the donors felt about their properties, any more than one must feel about Edward Colston as did the philanthropists of Bristol who chose to honour him in 1895?

For the nation

Take the National Trust’s collection of country houses. At the time of the Trust’s founding, most landowners objected in principle to the creation of a statutory body that would ‘sterilise’ good agricultural land by removing it from private ownership. Only a few prominent liberals in the landowning class thought there was a public-interest justification in preserving areas of outstanding natural beauty. These ‘enlightened’ few joined with conservationists, such as Octavia Hill, Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley, to found the National Trust in 1895 and to accept in 1907 statutory powers to ‘promote the permanent preservation for the benefit of the Nation of lands and tenements (including buildings) of beauty or historic interest’. (Nothing was said about the benefit of the donors.)

Again, most landowners had little idea and less concern about the ‘historical reputation’ of their properties. They were more concerned about keeping them afloat as profit-making enterprises at a time of agricultural depression. They cared more about the land (which they felt still held future value) than about their houses (which were often viewed as expensive encumbrances) and certainly more about the land than about their houses’ contents (which could be and were sold off in large quantities to stave off the sale of land).

Attempts to acquire for public benefit or even to ‘list’ their private properties were viewed as impertinences, or, worse, at a time of considerable political instability, revolutionary threats. It didn’t help that among the first aristocrats to donate their homes to the National Trust were the odd socialist (Sir Charles Trevelyan, whose Wallington Hall in Northumberland was in 1928 the first such property to be passed on to the Trust) or radical (Lord Lothian, who bequeathed his Norfolk seat, Blickling Hall, to the Trust in 1940).

A change of tune

It wasn’t until after the Second World War that some more (by no means all) landowners began to change their tune. The war had left, by neglect or requisition, many of their houses uninhabitable. The National Trust, which was now committed to recognising country houses as important historic buildings, was offering to take their houses off their hands, sometimes on highly favourable terms – for example, making informal agreements to leave the family in residence. (In these early years, the Trust was not necessarily expecting them to hand over land as well.) At this point, more landowners saw the value in playing up the ‘historic reputations’ of their homes, even claiming for themselves a role as ‘custodians’ for the ‘national interest’. Language that their parents and grandparents would have deemed ‘revolutionary’ seemed now better to serve their tastes and interests.

Mildly pornographic

If the owners remained in residence – as they did in the houses that remained outside the National Trust’s scheme but were now increasingly opened to tourists – then they retained a good deal of control over how the house was presented and interpreted. Their continuing residence was itself seen, for the first time, to be an integral part of the country house’s popular appeal. Even the most outré renovations (within the limits of listed-building status) could be approved as reflecting the unique taste and culture of the ‘family’; consider the psychedelic murals, some mildly pornographic, with which the Marquess of Bath decorated Longleat in the 1960s. Where the National Trust exercised its own control, one historical fashion succeeded another. Even ‘authenticity’ was a moving target, as houses that had accreted over centuries could be restored to any one of a number of past states. For a time the 18th-century pastiches of John Fowler were highly favoured, creating an ideal-type country house for the public to fasten on. Fashion has moved on, and some of Fowler’s re-creations are seen as far too imaginative.

If the variability of the ‘preservation’ of historic structures is so great, how much greater must be the variability of their interpretation. The most cursory glance at country-house guide books – which go back to the 18th century – will show you how differently they are viewed by successive generations. The Victorians loathed the Georgian: Murray’s Guide said of Petworth in 1863 that it had not ‘the slightest architectural attraction’, resembling ‘an indifferent London terrace’. Early 20th-century taste loathed the Victorian; there was then practically no Victorian building anywhere in the country that wasn’t slated for demolition. As late as 1961 the Duke of Westminster pulled down nearly all of his very grand Victorian country house, Eaton Hall. Tudor and Elizabethan associations have remained consistently popular, so much so that they get invented. At Chatsworth visitors were long shown Mary Queen of Scots’ apartments in a house that had essentially been demolished and rebuilt around 1690.

Myriad interpretations

The point is that great historic buildings are complex beasts with many layers and a myriad of possible interpretations. Each generation finds in them what it wants to find. Their ‘historical reputations’ cannot be and are not fixed, least of all by their ‘donors’, many of whom cared little for any historical reputation, others of whom had only recently discovered it. The right of private owners to destroy their own property was fiercely defended right up until the 1960s. Historic buildings are better protected today, by legislation and regulation, but ‘preservation’ can and does go only so far. New layers of interpretation are always being added; in good William Morris style, they add to but do not alter or destroy underlying layers. When the National Trust highlighted the East India Company connections of Osterley Park in West London – thanks to the innovative research of the historian Margot Finn and her ‘East India Company At Home’ team – it drew in to this somewhat neglected urban oasis large numbers of Asian residents of West London, who might never previously have given Osterley a moment’s thought. If attention to slavery and colonialism, or queer history, alerts new audiences to the tangled heritages of the National Trust’s country houses, how can that be a bad thing? These associations are not being invented; they are being uncovered. Previous generations had found them negligible, or unpleasant. They are cultivating for the current generations a new idea of ‘place and character’ to add to the old ones and keeping our heritage alive. Not to worry, Daily Telegraph, these new-found associations will be overlaid soon enough by something … newer.

Peter Mandler teaches modern British history at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge and is the author of The Fall and Rise of the Stately Home (Yale, 1997). His latest book is The Crisis of the Meritocracy: Britain’s Transition to Mass Education since the Second World War (Oxford, 2020).

Source: History Today Feed