Isle of Dogs | History Today - 11 minutes read

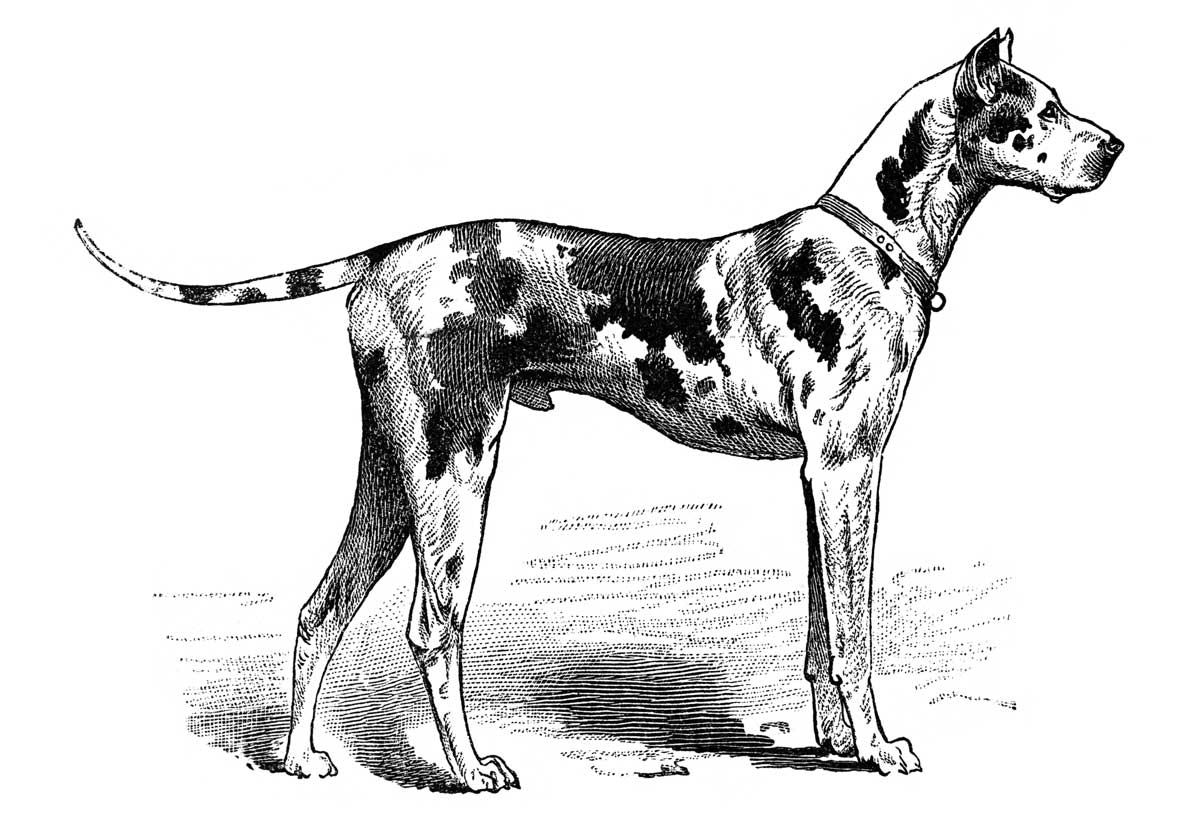

Dogs can be surprisingly mysterious animals, especially in fiction. Browse the shelves of your local library and I guarantee that, within a minute or two, you’ll find a book bursting with canine conundrums. There are dozens, if not hundreds of them: from Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles to Agatha Christie’s Dumb Witness. Invariably, they play on the proverbially close relationship between man and dog and discover some enigma in the pooch’s human (or inhuman) behaviour. Some dogs are noisy, hurtful, or cruel; others are loyal, gentle and kind. But none is more mysterious – or historically consequential – than Bendicò the great dane, in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1958).

Decline and fall

At root, The Leopard is a study of aristocratic decline, grounded in the realities of Italy’s past. Set in Sicily, in the late 19th century, it follows the fortunes of Don Fabrizio Corbera, Prince of Salina, as he attempts to grapple with the challenges of the Risorgimento. Alert to what is happening around him, he is alarmed by how greatly his family’s position is threatened by the unification of Italy and the rise of the bourgeoisie. But he soon realises that, if he wants things to remain as they are, everything must change. He must compromise with the things he despises in order to survive. Forgetting how he had winced when his penniless nephew, Tancredi, had joined Garibaldi’s redshirts, he helps to arrange the boy’s marriage to Angelica, the daughter of the wealthy but vulgar Don Calogero Sedàra, and recommends the latter for appointment to the Italian Senate in his stead. But it is all in vain. While Tancredi’s future is assured (albeit in an ignoble form), the Prince has done nothing to stop his own family’s demise. In time, their ‘degeneration … becomes ever more marked until’, eventually, ‘it reaches almost total collapse’.

In the sweep of Lampedusa’s tale, Bendicò appears to play a rather peripheral role. Though he appears frequently alongside his master the Prince, he is generally preoccupied with his own affairs and never does anything to move the plot along directly. Yet Lampedusa was adamant that Bendicò was the most important character of all. In a letter to Enrico Merlo di Tagliavia, written shortly before his death, he stressed that the great dane was ‘virtually the key to the entire novel’.

The question is: why? Given that Bendicò does so little, what makes him matter so much? And what does this say about Lampedusa’s understanding of Sicilian history?

All too human

As so often with canine mysteries, the answer lies not in what Bendicò does, but what his behaviour says about others.

Bendicò is, of course, just one of many animals to appear in The Leopard. Some – like the hunting dog Teresina – appear in their own guise, as bit players in the lives of the Prince’s family. More often, however, they are used to reflect (or satirise) the nature of particular characters – and to illustrate Lampedusa’s wider attitudes towards the Risorgimento in Sicily.

Many are critical; others poignant. Don Calogero Sedàra is pictured by the Prince as a woodcock, ripe for shooting; but, in reality, is a jackal, rat, or toad. His wife is a mare; his daughter Angelica is a bitch; and those who share his ambitions are hyenas. So, too, the Bourbon army, which is defeated at Gaeta, is compared to the rabbit shot by Don Fabrizio. And while the Prince sees the old nobility as lions, they are more like a cartload of newly slaughtered bulls.

The most prominent animal is, however, the gattopardo (usually translated as ‘leopard’, but more properly an ocelot or serval). The heraldic symbol of the princes of Salina, it is a reflection of how Don Fabrizio likes to perceive himself: proud, clever and – when necessary – ruthless. But the comparison is plainly ironic. Whenever it is made explicit, the Prince is behaving quite unlike a gattopardo, such as when his pride is hurt by aristocratic friends, or when he fails to cut Don Calogero down to size.

Bendicò’s role is to reveal Don Fabrizio’s true nature. Though the comparison between the two figures is never made explicit, his ‘all-too-human’ behaviour is always portrayed in dialogue with the Prince’s own – and helps to explain why Don Fabrizio so signally fails to rescue the Salina’s fortunes. As such, Lampedusa effectively uses Bendicò to narrate the ‘real’ story of the book; and, in doing so, sets out an original, if critical, interpretation of the collapse of the Sicilian nobility more generally.

A dog’s life

For Lampedusa, the ‘otherness’ of the Sicilian aristocracy was crucial to understanding their demise. They inhabited a different social world from most people – and even had different origins. Bendicò’s first task is thus to set Don Fabrizio apart from his surroundings. This is, in part, achieved simply by stressing their physical resemblance. Just as Bendicò is much bigger than other dogs, so Don Fabrizio is a ‘god’ among men. He is so ‘large and tall’ that his head touches the chandeliers and can ‘twist a ducat coin as if it were mere paper’. But it is also achieved by underscoring their foreign origins. When Bendicò makes his entrance, he is identified as an alano. This literally means ‘great dane’; but it can also mean an ‘Alan’. As Lampedusa knew, the Alans were a Germanic people who invaded Italy in the fifth century and briefly ruled over Sicily. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, they also had ‘yellowish hair and frighteningly fierce eyes’. The Prince is no different. Though a proud Sicilian, he is descended from German stock – and boasts not only ‘fair skin and hair’, but also a ferocious gaze.

For Lampedusa ‘foreignness’ in itself was not a fault, of course. Over the past 25 centuries, Sicily had been invaded by many ‘superb and heterogeneous’ peoples, each of which had tried to change the island for the better. The problem was that, being strangers, they had each been undone by Sicily itself. As the Prince explains, the ‘violence of the landscape’ and the ‘cruelty of [the] climate’ had cast a ‘voluptuous torpor’ over its people. This made them resent action and hate change. Those who came to the island as rulers were hence ‘detested and misunderstood’. Their art and culture were treated with bemusement; their taxes despised; and their presence begrudged. Soon enough they, too, fell back into inaction – and allowed their native virtues to degenerate.

Nothin’ but a hound dog

One of the consequences of this was a decline in moral and civic standards. This is, admittedly, not immediately obvious from Don Fabrizio’s bearing. He is a deeply pious man, who prays the rosary every day. He is also a learned astronomer, whose discoveries have been recognised by the Sorbonne and who feels himself above the sordid confusion of Sicilian life. He worries endlessly about the fate of the Bourbon monarchy and believes himself to be a loyal subject.

Initially, Bendicò only seems to emphasise his master’s rectitude – albeit by contrast. While the Prince frets about the future, Bendicò behaves exactly as we might expect. Though loyal and affectionate, he is boisterous to a fault and loves nothing better than enjoying simple earthy pleasures, heedless of the damage he ends up causing. Racing into the garden, he rummages gleefully around in the plants ‘growing thick with disorder in the reddish clay’, oblivious to the fact that he has broken 14 carnations, destroyed a hedge and blocked a channel.

But in reality, the Prince is just like his dog. A few hours after Bendicò wrecks the garden, Don Fabrizio sets off for battle-torn Palermo. There, instead of defending his king (or joining the rebels, like Tancredi), he passes his time making love to a peasant girl named Marrianina, much to his wife’s dismay. And, in doing so, he effectively speeds the decline of the Bourbon monarchy – and ruins the ‘garden’ of Sicily.

Far more troubling, however, was the demise of feudal structures – and the decline of aristocracy itself. Once again, this is a fault from which Don Fabrizio does not, at first, seem to suffer. He is, after all, ferociously proud of his family name and never loses sight of the fact that he is ‘among other things, a Peer of the Kingdom of Sicily’. But in Bendicò’s behaviour, we see just how completely he destroys his ability to support himself – and his cherished nobility.

All bark and no bite

After Garibaldi’s landing, the Prince and his family leave Palermo for their country residence at Donnafugata. There, he receives two of his tenants, who bring him some of their rent in kind. Among the produce are eight chickens. Tied upside-down by their claws, they ‘twist in terror’ as Bendicò sniffs around them. Noticing this, Don Fabrizio reflects on how foolish their fear is. While Bendicò looks fierce, he is actually very gentle – and wouldn’t so much as touch a chicken bone in case he got belly ache. What Don Fabrizio doesn’t realise is that Bendicò’s manner is typical of how torpid he has become with his tenants. Though they had long regarded him with awe, he has grown soft with them. Too often, he forgets to demand his dues and his growing kindness is already costing him their respect.

Precisely because Don Fabrizio is so much like Bendicò, he is sliding into financial difficulties; and he cannot help comparing his mounting debts with Don Calogero’s profits. He knows that he must be more ruthless. But he is unable to do anything to save himself. Just as Bendicò runs after Tancredi at every opportunity, so the Prince, driven by misplaced loyalties, is blind to the interests of anyone but his nephew.

Deep down, Don Fabrizio knows he is wrong. Though he helps arrange Tancredi’s marriage, he – like Bendicò – is aware that an alliance with such a lowborn family is harmful to his dignity. When Angelica comes to visit after her engagement, Bendicò growls at her from the back of his throat. But just as the dog is called to task by the Prince’s son, so Don Fabrizio allows ‘modernity’ to overrule his better judgement.

Sicily has corrupted him too much even to recognise the last chance he has of renewing his status. When a representative of the new government comes to offer him a seat in the Italian Senate, he is initially tempted. Yet, once Bendicò has entered, sniffed the newcomer and fallen asleep under the window, Don Fabrizio, too, is overcome by ‘voluptuous torpor’ one more.

A dead dog’s day

When Bendicò next appears, half a century later, the consequences are plain to see. Dead for more than 45 years, the great dane is now just a stuffed animal, full of moths and tucked away in a corner of a bedroom. As the Prince’s now-aged daughter Concetta notes, he is the object of comforting nostalgia. But he is also a sign of how far the family has fallen. While Tancredi and Angelica are powerful, if debased, figures, at the summit of the new regime, the Corbera live on the tattered relics of the past. Eventually, it becomes too much. Disgusted by the grim reality of modern Sicily, Concetta orders Bendicò to be thrown out – and with him the memory of her father.

Yet as Bendicò’s corpse is thrown from the window into the courtyard below, the wind seems to bring him to life once again; and for a second, soaring through the air, he takes on feline form. It is a last, painful irony. For it is only in death, when Don Fabrizio’s fallible nature has been stripped away by time and the void of eternity awaits him, that this fly-bitten mongrel looks like the gattopardo he always wished to be.

Lampedusa could not forgive the Sicilian nobility for conspiring in their own fall; but, in the end, he appears to have believed that, in retrospect, even dead dogs had their day.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book is Machiavelli: His Life and Times (Picador, 2020).

Source: History Today Feed