A Spiritual Wilderness | History Today - 2 minutes read

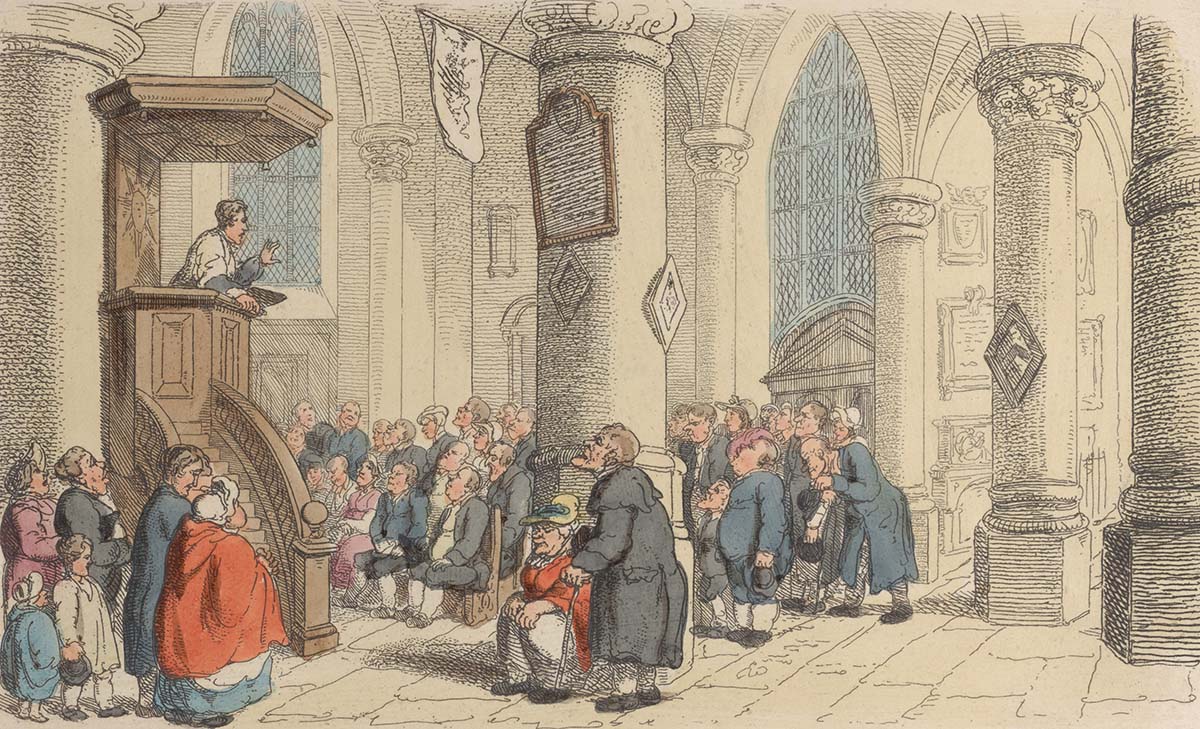

The image of the idyllic country church, filled morning and evening, Sunday by Sunday, by every stratum of a village’s society, is a familiar one. It has provided stock characters for Anthony Trollope, evidence for decline seized on by secularists and a sense of a lost Christian nation lamented by church leaders. It fills pages of local village histories, coloured with nostalgic reminiscence. The faded sepia photographs often still hang in cobwebbed frames in a corner of the church’s vestry. ‘Everyone’ went to church then. ‘All the children’ went to Sunday school. It is part of the national narrative about the 19th and early 20th centuries.

This picture, however, may be more nostalgia than reality. Research into villages in Wiltshire, for example, has uncovered a startlingly different story of church-going in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. One vicar wrote that he felt that he had been ‘landed for life’ in ‘a spiritual wilderness’.

In the picturesque hamlets and small villages that wind through the Nadder, Ebble and Wylye river valleys before they merge into Constable’s majestic Avon, the sheep, wool and cloth trade flourished, reliant on the chalk streams and the West Wiltshire Downs which roll gently above. The villages still nestle around churches which stood long before the Dissolution wreaked havoc upon their patrons, Shaftesbury, Glastonbury and Wilton Abbeys. We find history here, deep, earthy and rooted.