The Black Legend Written in Silver - 3 minutes read

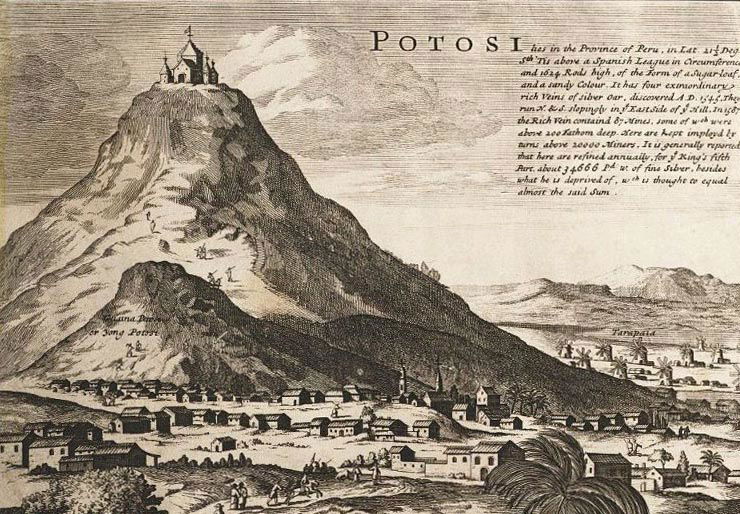

A dry, cold, desolate mountain in the high Andes seems an unlikely location for a city that, at the end of the 16th century, had a population of 120,000 people and was three times the size of London. Located at 4,000 metres, Potosí’s phenomenal growth was based on vast deposits of silver found in the towering Cerro Rico, or Rich Hill, in 1545. Its reputation spread quickly and widely, with images of the city produced as far away as the Ottoman Empire in the 1580s and on Chinese maps a few decades later.

At the peak of production in the 1590s, roughly 200,000 kilograms of silver were mined each year, not counting thousands more that escaped official records. Potosí’s silver flooded the global market; the wealth it generated stimulating demand for, and the production of, linen and fine cloths from the Netherlands and France, as well as silk and porcelain from China and cotton cloths from India. It enabled Spain to conduct costly European wars and to overcome the Ottomans.

Potosí’s fame was not only dependent on its wealth. It became notorious for the appalling conditions under which miners, ore crushers and smelters laboured. Printed illustrations of work in the mines promoted the image of Potosí as ‘the mouth of hell’ and fuelled the Black Legend that saw the Spanish as cruel and greedy.

It is not surprising that scholars have generally focused on Potosí from economic and global perspectives. Kris Lane stresses how the local was linked to the global, focusing on everyday life in the mines and city. Covering the period from the discovery of silver until 1825, he uses personal stories gleaned from original sources to produce a rich and lively account that shows how elite merchants, officials and mine owners rubbed shoulders with African slaves, native residents and migrants. He also shows how, like all mining frontier towns, Potosí was a violent, immoral and polluted place, but at the same time was dynamic, opulent and offered opportunities for social advancement. It constituted a huge consumer market that demanded necessities for miners, such as thick clothing, chicha (maize beer) and coca (to enable work in the rarefied air and suppress hunger).

Even though the Cerro Rico may not have consumed the eight million lives that the Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano suggested in the Open Veins of Latin America (1971), work in the mines and smelters was dangerous and the death toll was high. This was not the only human cost, as Lane shows. The effects of labour mobilisation under the Spanish were also considerable. From 1570, the mustering of 13,500 men a year from indigenous villages from Cuzco in Peru to Tarifa in modern Argentina disrupted agricultural activities, separated families and wrecked community life, while causing widespread flight to escape being taken. Native leaders responsible for fulfilling the quotas often had to hire replacements. One leader claimed he had to sell his mule and llamas and even pawn his daughter to a Spaniard.

Lane also addresses the environmental consequences of mining, so evident in the polluted, scarred landscape we see today, and other disasters, such as floods, food shortages and epidemics. Reflecting the author’s mining background, the book discusses how engineers of different nationalities sought to deal with the technical challenges of mining and mineral processing at Potosí. As this beautifully written book shows, the costs and benefits of globalisation are not confined to their historical moment.

Potosí: The Silver City that Changed the World

Kris Lane

University of California Press

272pp £26

Linda Newson is director of the Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of London.