The War in Words | History Today - 5 minutes read

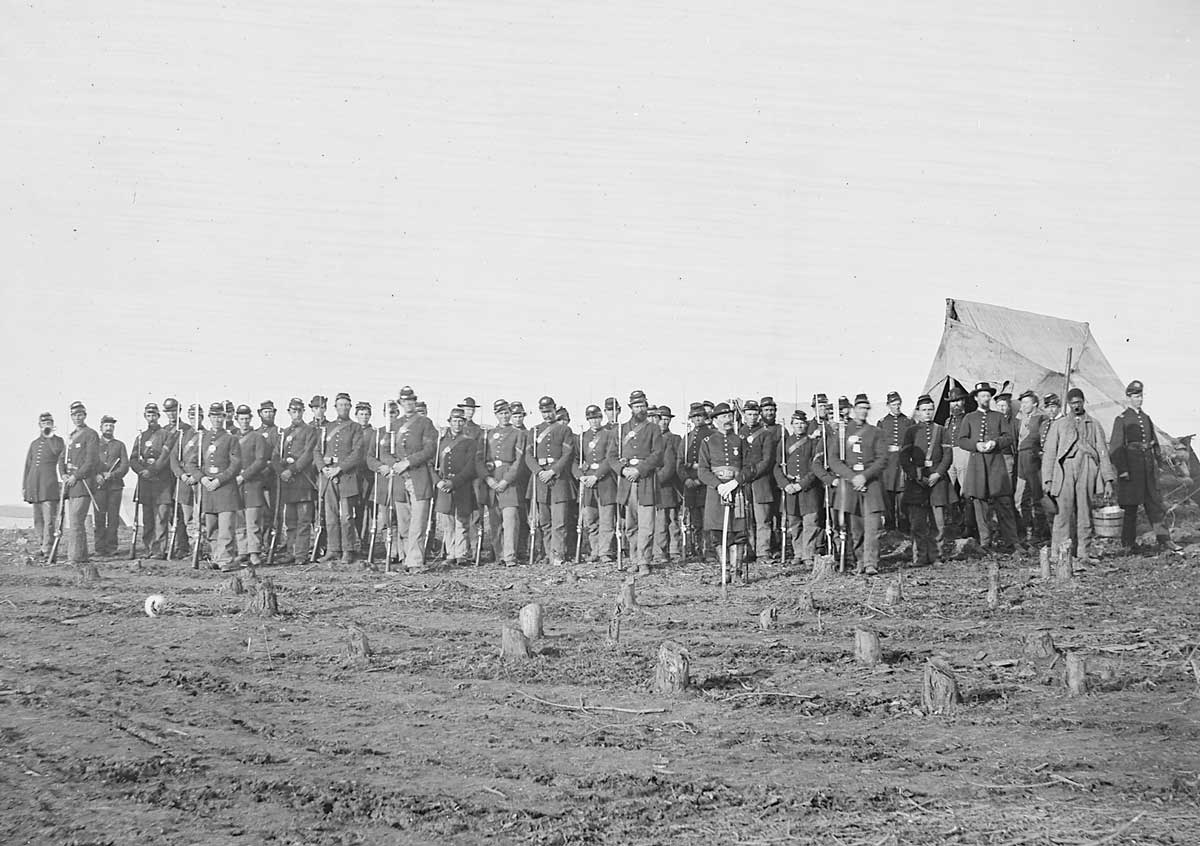

The American Civil War burned itself into the American identity as the Union and Confederacy fought across large swathes of the country and an estimated 600,000 people died, more US casualties than in any war before or since.

For the rest of the world, the stakes were much lower. The US had not yet fully grown into the economic and military power it would become in the 20th century. While its internal conflict was often reported in the global press and was the subject of academic interest, it was not a vital national security concern. What did outside observers, particularly those in the UK, think of the conflict?

One source of insight comes from the digitised archives of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). The Institute still exists today, functioning more or less as a think tank with its journal acting as an academic publication. In its early days, the journal was a collection of short papers on new technologies, current military affairs and lectures given to the institute’s members, with topics ranging from innovative ways to serve tea and coffee en masse to soldiers in India, to the proper shape of swords. Today it forms a valuable resource into the insights and opinions of the UK’s officer corps in the mid- to late-19th century.

Three RUSI lectures dealt with the American Civil War as it was happening, one given by Major Fredrick Miller in 1862 and the others by the Sandhurst professor Captain Charles Cornwallis Chesney in 1863 and 1865. The latter author is notable for being both the nephew of British explorer Francis Rawdon Chesney and older brother to George Chesney, who precipitated the genre of invasion literature with his novella The Battle of Dorking (1871). Miller and Chesney’s lectures describe the course of the war up to that point, with Chesney focussing first on fighting in Virginia and then on operations in the west and south, such as Sherman’s March to the Sea.

Their most obvious limitation is distance from the conflict. The beleaguered lecturers frequently expressed their annoyance at the state of information they received from across the Atlantic. Like many of today’s open-source analysts, they sought to make sense of events when, as Miller reported, the newspapers:

are as apt to confuse as much as they inform us … They give one day flying reports which they contradict the next, and they republish the same incidents in a new form a month afterwards.

The delay in receiving information is most apparent when Miller concluded his lecture discussing the Battle of Shiloh, which had occurred about two weeks earlier. He dubbed it ‘the greatest battle ever fought in America’, but could not yet describe the battle or its importance to the war as a whole to his audience.

Similarly, some key events in the modern popular understanding of the Civil War are downplayed. The combat between the Monitor and the Merrimac, notable for being the first clash between ironclad ships, is referenced but purposely not discussed because ‘the result has not influenced the military progress of the war’.

Amid largely accurate descriptions of the various manoeuvres, battles and logistical challenges, the judgements and opinions of the lecturers shine through the text. For instance, there is a great deal of frustration and confusion over the conduct of the war’s early stages, which Miller labelled ‘desultory marches and petty skirmishes’. The authors note that, given the Union’s resource advantages, their lack of success under General McClellan must have been the result of incompetence by the Union’s officers and the quality of Confederate leadership. Miller offered particularly strong words on the discipline exhibited by soldiers, claiming that ‘they embrace every variety of disorder, from the careless use of arms and the independence of sentinels on duty, to attacks on officers and mutinies in regiments’. He also noted as early as 1862 that the South is ‘approaching a crisis, which has only been hitherto deferred by the inability of the North to wield its weapons of offense’. In his lectures, Chesney laments that Sherman, in his March to the Sea near the end of the war, ‘has given no voucher or note anywhere for the supplies he has seized [from civilians]’ and expresses concern about whether the North and South could be reconciled, given the brutality of the conflict.

In some cases, the conduct of the Civil War was used by British officers to justify their own opinions of how the UK should prepare its military for future wars. Prince George, the Duke of Cambridge and chair of the 1865 lecture, concluded after the address that the conflict reinforced, ‘the absolute necessity of a large, handy body of cavalry’. The Duke of Cambridge, who was Commander-in-Chief of the Forces for nearly 40 years and Queen Victoria’s cousin, represented a more traditional school in British military thought that insisted on the continued prominence of cavalry in its historic role, even as technological developments made their conventional use more and more dangerous. The doctrinal clash would come to a head in the Second Boer War and the cavalry morphed into a more versatile force that could also fight on foot as mounted infantry when the situation required it.

The RUSI lectures demonstrate the challenges of following a war as it is occurring from a distance, the disappointment with the Union’s military performance early in the war and the manner in which foreign conflicts were mobilised to justify the policies of people like the Duke of Cambridge. When accounts are understandably dominated by American sources, the insights of those removed from the battle offers an fascinating perspective on a conflict that had not yet been decided.

Marcel Plichta is a PhD student at the University of St Andrews and former intelligence analyst for the US Department of Defense.

Source: History Today Feed