The Sauce of the Middle Ages - 6 minutes read

If the name Charles Dyson Perrins strikes a chord of recognition today, it is probably in connection with the Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce developed by his grandfather, which helped create the family’s fortune. In Worcestershire, Perrins’ name remains associated with his many philanthropic projects, from hospitals to the Dyson Perrins Church of England Academy. But for scholars of manuscripts he is known because of the imposing catalogue of 135 volumes written for Perrins by George Warner, retired Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum, published in 1920.

As with most early 20th-century collections, however, the catalogue only includes a selection of the manuscripts that passed through Perrins’ hands – those deemed most significant. Tracing Perrins’ collecting habits through dealers’ records, meanwhile, builds up a fuller picture. What is revealed by this are the ways in which lavish publications such as Warner’s catalogue have helped reinforce ideas about what is considered an ‘important’ manuscript – and in turn influenced the shape of Medieval Studies as a discipline.

The varying values placed on medieval manuscripts by wealthy collectors such as Perrins, scholars like Warner and other people involved in the early 20th-century book trade have had an outsized impact on the ways in which the Middle Ages have been perceived, both within the academic community and by the wider public.

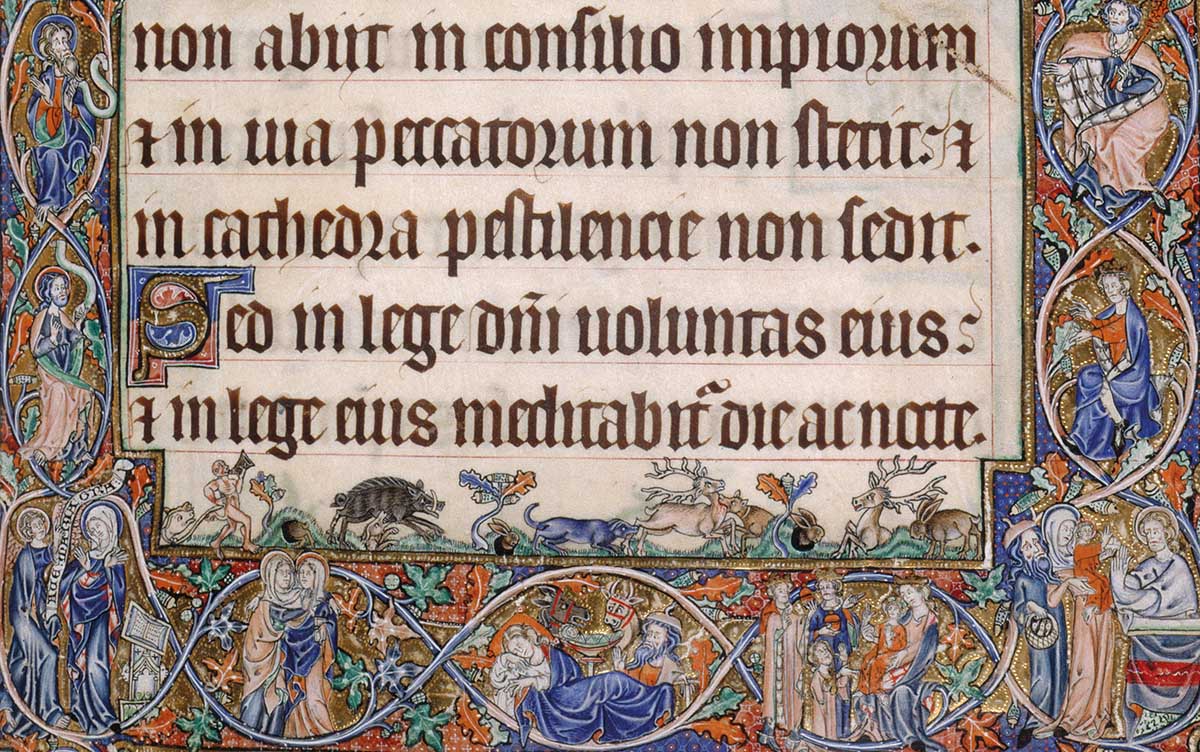

Perrins’ first major purchase of a manuscript became a legend of the book trade. The story goes that in July 1904 Perrins went into a bookshop in search of something to read on the train. He came out with a large and richly illuminated 14th-century psalter, which he took home for inspection. The asking price was £5,250 (very approximately £500,000 today), so Perrins sought the opinion of an expert, Sydney Cockerell, a former secretary to William Morris, who was then earning a living writing catalogues for collectors. Grasping the opportunity, Cockerell advised Perrins to buy it and went on to write a monograph on the psalter (now known as the Gorleston Psalter and held in the British Library) and include it in his 1908 Burlington Fine Arts Club exhibition of illuminated manuscripts in London.

Although the purchase of the psalter represented a huge increase in his spending on manuscripts, Perrins had bought medieval manuscripts before, as an extension of his interest in early printed books. Indeed his collection focused predominantly on late medieval and renaissance books, with a preference for illuminated material. Only part of his collection of early printed material (the Italian books) was ever published and this, together with the treatment of books and manuscripts in separate publications, has helped focus attention on his manuscript collecting.

The first documented purchases of manuscripts by Perrins are in 1902, but he was prepared to buy in bulk, purchasing, for example, the Sussex collector Richard Fisher’s entire collection of manuscripts and early printed books in 1906 and at least 40 manuscripts from the artist Charles Fairfax Murray in 1905-6. In 1907 Cockerell began work cataloguing Perrins’ growing collection of manuscripts and it was probably under his guidance that Perrins sent 43 manuscripts and over 400 printed books for sale anonymously at Sotheby’s. Cockerell believed that rich men should only own the highest quality material and later advised another new collector, Alfred Chester Beatty, to sell half his manuscripts. Some of Perrins’ manuscripts raised less than he had paid for them, indicating both the capricious nature of the market and Perrins’ relative inexperience at the start of his collecting. But the sale also suggests that manuscripts were not necessarily valued more than printed books. The top two prices were for manuscripts (copies of Ovid’s ‘Fables’, sold for £200, and the 13th-century French poem Roman de la Rose, sold for £190), but the next highest price was for a 15th-century printed psalter (£128) and a printed book of hours sold for more than any of the manuscript hours (£79), even one described in the auction catalogue as ‘very brilliant’, with ten full-page and six small miniatures, which fetched £55. The printed hours was described as ‘extremely rare’, but any manuscript hours was, as a hand-made object, unique.

Cockerell used 50 of Perrins’ remaining manuscripts as the basis for the Burlington Fine Arts Club exhibition and, following its success, he was appointed director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The task of cataloguing Perrins’ still-growing collection of manuscripts then passed to Warner. The publication of the exhibition catalogue and Warner’s, with its large black and white illustrations, made parts of Perrins’ collection accessible (if only through reproductions) to a wider audience than those able to consult manuscripts at his homes in Malvern and Ardross Castle in Scotland, and consolidated his reputation as a collector. These, and the other publications sponsored by Perrins, became important reference works as the study of manuscripts developed.

Perrins was part of a growing tradition of publishing illustrated catalogues of private collections, following in the footsteps of the collector of illuminated manuscripts, Henry Yates Thompson. However, the physical size of his imposing two-volume catalogue (about 40 x 30 cm) was in itself a statement about the value of this collection and Perrins’ importance as a collector.

In 1932, Belle da Costa Greene, librarian and director of the Morgan Library in New York, joked that ‘elaborately printed catalogues generally presage’ the sale of a collection, but, although Perrins’ acquisitions of manuscripts decreased dramatically after 1920, he retained the collection until his death in 1958. His will directed that two manuscripts (including the Gorleston Psalter bought in 1904) be given to the British Museum, two more to his widow and the rest sold, with the proceeds divided between his wife and children. The first of three major sales took place in 1958 and set a record total of £326,620 (approximately £7,500,000 today) for a one-day sale of books and manuscripts. The manuscripts have since found new homes in Britain, the US, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland and Australia.

Stories such as Perrins’ serve as important reminders of the wider impact of collecting. The tastes and financial resources of individual collectors, and the collections they built up, often shape our access to the past as much as the objects within them. The manuscripts owned and studied in this period tend to have found homes in well-known collections and received further study, while those that did not are usually much harder to trace.

Laura Cleaver is Senior Lecturer in Manuscript Studies at the Institute of English Studies. A version of this article was originally published in Talking Humanities, the blog of the School of Advanced Study, University of London.