Choosing Sides | History Today - 6 minutes read

On the US Western frontier in 1861, a dangerous hodge-podge of competing political interests created a bloody contest six years before the shots on Fort Sumter split the North from South and led to the Civil War. In this tinderbox, Native Americans faced enormous pressure to choose sides. General John C. Frémont, long accustomed to using native scouts and interpreters, expressed interest in Native enlistments for the conflict, as did the unionist and militia leader, Jim Lane. However, the Lincoln administration had no intention of enlisting or arming Native Americans, fearing how whites on the frontier would respond to the perceived threat of Indian violence, preferring instead that they ‘confine themselves to peaceful avocations’. The administration naively hoped to keep Native people out of the conflict altogether.

The Confederacy, however, actively courted western tribes. The Confederate Indian Commissioner Albert Pike struck a mutual assistance peace treaty with the Five Nations Cherokee, then living in Indian Territory, or present-day Oklahoma. He was less successful with smaller tribes, in part because Pike travelled in the company of the notorious Texas Cavalry, known for its brutal harassment of western tribes. When the cavalry took over Fort Arbuckle and Fort Cobb in Oklahoma and declared its intent to ‘sweep the Territory from the Texas border to the Kansas line, “cleaning out” northern men everywhere’, smaller tribes, which had been reliant on federal support, were dismayed.

The Southern band of Leni-Lenape Delaware, led by Black Beaver (Sucktummahkway), a US Army scout, and sub-chief Jim Ned (of African-Native descent), were staunchly unionist. So, too, were their Kansas cousins on the Delaware Reservation near Fort Leavenworth. The chiefs Anderson Sarcoxie, Neconhequin and John Conner urged peace among the tribes on the frontier and support for Lincoln, ‘who is now using all his lawful power to preserve the Union’. Black Beaver and Ned called on unionist tribes in Indian Territory to head for Kansas, believing that Texans would soon overrun the region. Sensing an opportunity, the Union’s Indian Commissioner E.H. Carruth sent out word in mid-September that Black Beaver would head a delegation of loyal tribes and offered to arm them against the Texans.

In late November 1861, with snow and temperatures falling, a mixed tribal group of about 5,000 people led by the Creek principal chief, Opothleyoholo, left Indian Territory in a long train of wagons, women, children and herd animals. They travelled north towards Kansas in the hope of sheltering with the Union cavalry stationed at Fort Roe. Black Beaver’s Delaware joined the refugees heading towards the Delaware reservation and Carruth’s promised aid.

Almost immediately, however, Confederate Creek and Cherokee raised alarms under the pretext that the refugees had stolen enslaved people from the Five Nations reservation. Chiefs Stand Watie and Chilly McIntosh joined the Texas Cavalry in launching a punitive expedition against the supposed kidnappers. They engaged the refugees in battle in November at Round Mountain, resulting in a Confederate defeat, and again at Chusto-Talasah in December, where four hours of brutal fighting beat back the Confederate assault. But the exhausted refugees were hard-pressed to make another stand, as bitter cold and the strenuous fighting took their toll. Caught at Chustenahlah on 26 December, the Confederates, Watie and McIntosh smashed Opothleyoholo’s meagre defences and hunted down the fleeing refugees for over 200 miles, capturing and killing old men, women and children as they went. Confederate reports stressed the number of captured animals, prisoners and enslaved persons, gloating that the refugees in Kansas were now destitute. Survivors called their journey the ‘Trail of Blood on Ice’.

News of the refugee crisis proved electric. The unionist Jim Lane demanded an expedition, which would include his own Delaware scouts led by Captain Falleaf, to destroy the threat posed by the Five Nations, regain control of the frontier from the Texans and return the refugee tribespeople safely home. Some doubted very strongly that Lane’s goal was anything more than an excuse to raid and plunder, dubbing it the ‘great jayhawking expedition’, but events had forced Lincoln to relent. In January 1862 Lane was authorised to raise 8,000-10,000 men for an expedition against the Cherokee in Indian Territory, which could include up to 4,000 native volunteers and refugees. Opothleyoholo, writing to Lincoln about the rough condition of the refugees, promised the president they would destroy the rebels ‘like a terrible fire on the dry prairie’.

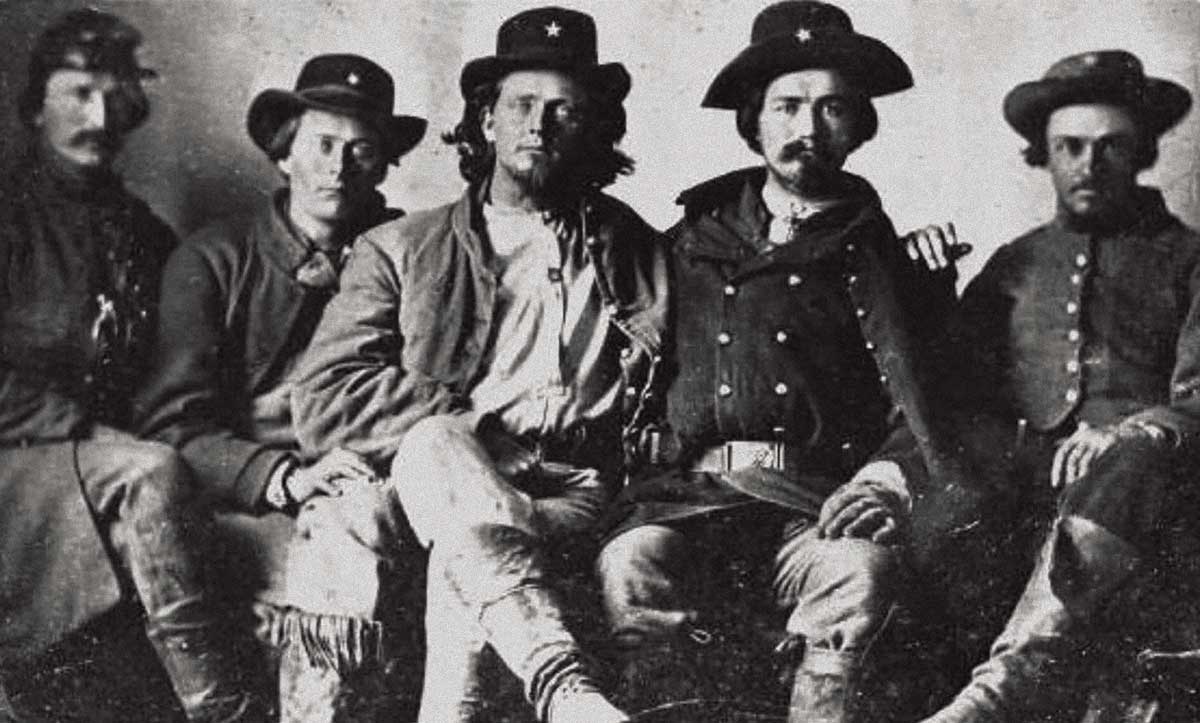

The War Department refused to enlist Native American volunteers into regular units, so they served under the auspices of the Department of the Interior and the State of Kansas. White army officers had command, but the company commanders were largely Native American. Known as the Indian Brigade or Home Guard, this was the first time the Interior Department had ever enlisted or armed Native Americans. Southern Delaware furnished enough volunteers for two complete regiments. Opothleyoholo’s band formed the Creek and Delaware 1st Indian Home Guard. A mixed group of Kickapoo, Osage, Seneca, Shawnee and unionist Five Nations made up the 2nd Home Guard. The 3rd and 4th Indian Home Guards were Shawnee, Muncie, Stockbridge and Delaware from Kansas. This is also the first time that men of African American and African-Native descent were enlisted and armed for Federal service. The 1st Kansas Colored Regiment, recruited in August 1862, served alongside their Native American and white compatriots in what was the most racially diverse force in the entire Civil War.

Unfortunately, the Indian Expedition of 1862 ultimately failed to return the refugees to their land in Oklahoma. They remained encamped at the Union Forts Gibson and Scott in the unstable borderlands, reliant on federal protection. Indian Brigade and Guard units were used in expeditions into Missouri and Arkansas, fought against the Tonkawa and made annual incursions into Indian Territory. Captain Falleaf’s scouts even joined the Sibley expedition against the Sioux in 1864. The war’s end saw the refugees safely home.

For the Kansas Delaware, their service was bittersweet. Highly respected during the war but unable to protect their own land from white bushwhackers, they were removed to Indian Territory in 1866.

Megan Nishikawa is a doctoral student at Liberty University, Virginia.

Source: History Today Feed