Academic Debts | History Today - 2 minutes read

The political commentator Jenni Russell, in a column in The Times published last November, compared the popularity of history as a subject for books and TV – citing Yuval Noah Harari, Amanda Foreman and The Crown – with the decline in the numbers of students studying history, both at school and at undergraduate level.

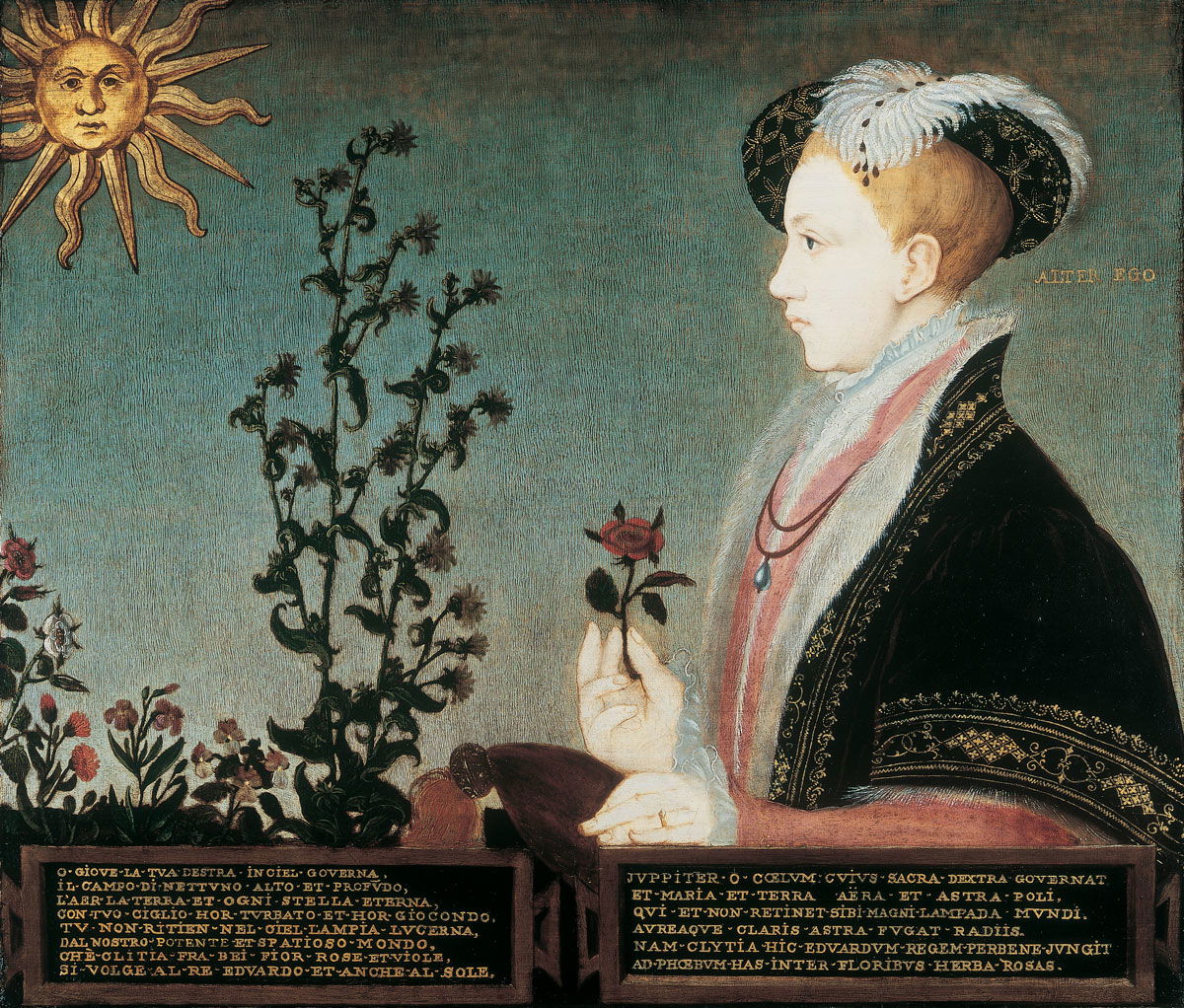

Russell argues that this decline may be because too many books produced by academics are ‘specialised, inward-looking, jargon-ridden and impenetrable to outsiders’. She picks out, unfairly, I think, Diarmaid MacCulloch’s recent biography of Thomas Cromwell, which, 130 pages in, overwhelmed her with its ‘interminable details and digressions’. I was surprised that MacCulloch bore the brunt of Russell’s criticisms because, if there is a senior academic I would regard as skilled at writing for a wider audience, it is he: his study of Edward VI, Tudor Church Militant, is both accessible, scholarly and groundbreaking, and a personal favourite. His Thomas Cromwell was not a disappointment to me.

But Russell’s argument points to an age-old dilemma. Inescapably, by their very nature and purpose, many academic books are academic books, written for small circles which nevertheless advance, even if glacially, our knowledge of a period, person, or event. Others seek a wider audience, and this has always been a tension at the heart of history: it is a discipline in which everyone feels they have a stake.

Writing for a wider audience is a balancing act, between academic rigour and attracting an audience that seeks and expects an accessible narrative peopled with characters and incident: I know how difficult that tightrope is to walk, having now written a book on Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate, which is intended to be just that. I hope it isn’t jargon-ridden and impenetrable – history books do not have to be, as Catherine Fletcher’s new history of the Renaissance demonstrates, as does Andrew Roberts’ latest, Leadership in War – but if it wasn’t for the stuff that ‘no one reads’, we wouldn’t have the books that people do.