Solving the Riddle of Reproduction - 9 minutes read

Science claims to be objective, yet both its past and its present are riddled with myths. Stories that have repeatedly been proved wrong continue to be told – that Isaac Newton conceived the theory of gravity because of a falling apple, or that Charles Darwin found clinching evidence for evolution when he studied finches on the Galapagos Islands. While such fables are easy to dismiss, fairytales survive at the very heart of scientific knowledge.

Consider reproduction. According to traditional accounts, a female egg waits patiently inside her owner’s womb like Sleeping Beauty imprisoned in a castle. At last, a troop of valiant knights arrives to rescue this damsel in distress, vying against each other until the fastest and the strongest breaks through her fortifications to ensure his genetic survival. Recent research favours an alternative scenario that emphasises the female role. Metaphorically, spermatic soldiers thrash about enthusiastically but ineffectually until the egg gently guides them in the right direction, temporarily lowering her chemical defences to admit a suitor.

Preformation

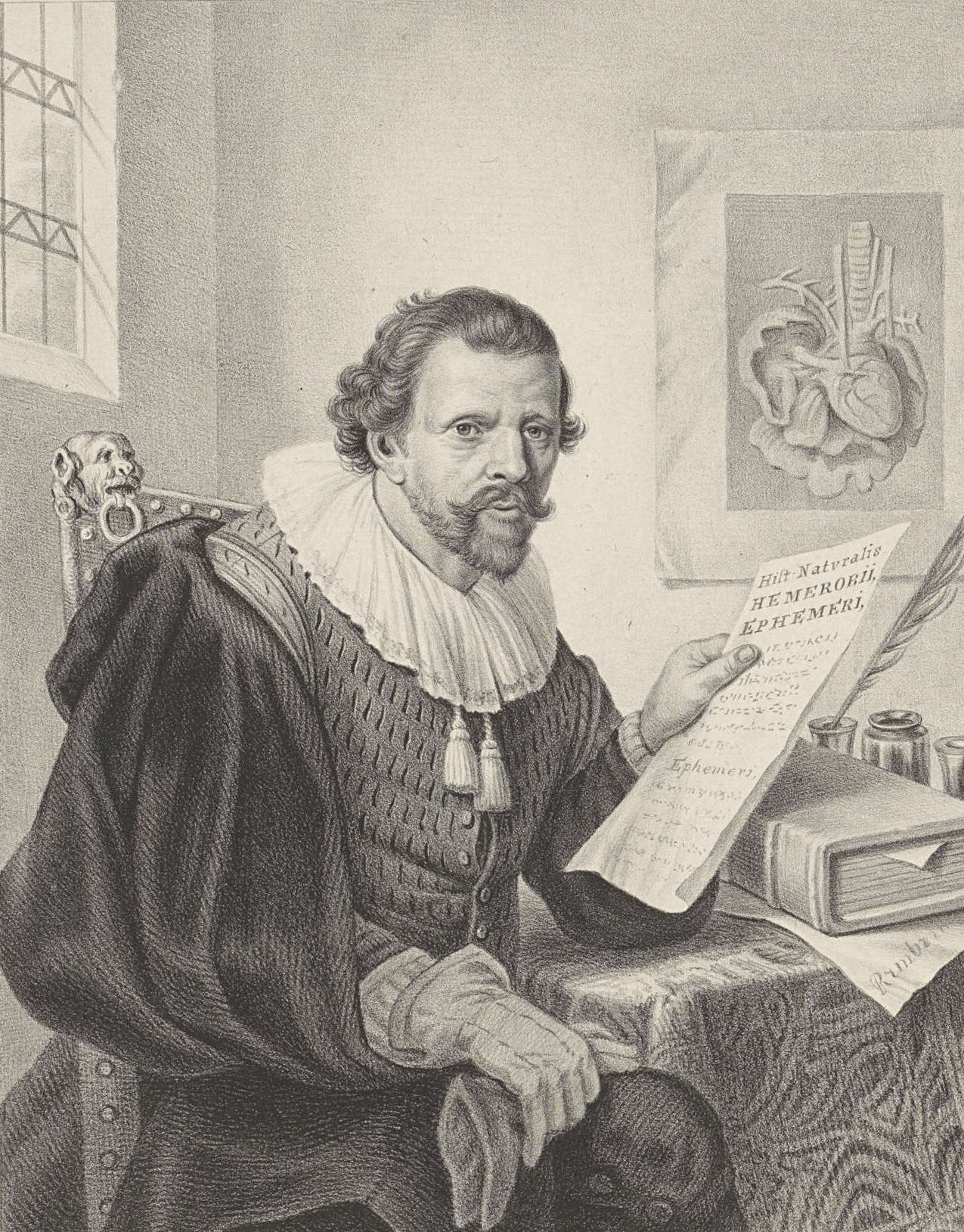

Unsurprisingly, male-dominated accounts of reproduction have a long history going back to the Greeks. Although Aristotle is most famous as a philosopher, he was also a keen biological observer, and for hundreds of years his followers maintained that reproduction takes place when an active male seed implants itself inside a receptive, nurturing female environment. According to romanticised versions of the past, this model was definitively overturned by the doctor William Harvey in 1651, long after his more famous demonstration that blood circulates round the body.

In the traditional mythology, Harvey features as a lone discoverer who first suggested a model closer to modern beliefs – that separate ‘parts are not fashioned simultaneously, but emerge in their due succession and order’. In other words, that new life develops in a sequential process. As the king’s physician, Harvey enjoyed privileged access to the royal deer parks, where he carried out field work as an antidote to his chronic insomnia. Eventually he let himself be persuaded by a friend into publishing details of his research into chicken eggs – the most common source of information – as well as deer and other animals. Yet however prescient Harvey’s insistence on a progressive model might now seem, at the time his insight was largely ignored. Buried inside paragraphs of dense Latin prose, it was easily dismissed as a late aberration by an elderly scholar.

Instead, researchers focused on a theory that, although long-lasting, is often ridiculed as a temporary detour from the road to true knowledge. Technically known as preformation, this model claims that, instead of developing gradually before birth, miniature organisms have already been in existence – created in advance, they are gradually revealed or unfolded. Preformation’s proponents divided into two opposed camps: the ovists placed tiny future beings inside the egg, while the spermists favoured the male sperm cells. Or as the biologist Clara Pinto-Correia has memorably expressed it, this was a battle between the followers of Eve and of Adam.

Eve’s Russian dolls

Like other discarded hypotheses, preformation sounds absurd. Idealised versions of history ignore this debate because both sides lost and no glorious victor emerged. Eventually, both ovism and the short-lived spermism were vanquished by a developmental model, but this was no trivial tussle between fringe charlatans: for 150 years, mainstream experimenters remained convinced that preformation would provide all the answers.

One of their strongest arguments was that ancient philosophical precept: ‘Nothing can come of nothing.’ How could a fawn or a child or a chicken possibly be produced without having existed beforehand? Harvey’s suggestion was hard to believe and impossible to verify. It was also deeply unfashionable. In the middle of the 17th century, Aristotle’s invisible powers and tendencies were out, while René Descartes’ mechanical model was in. As a core principle, it maintained that any change demands a cause: just as billiard balls lie stationary until hit by a cue, so too biological organisms cannot alter spontaneously without an external force.

When faced with uncertainty and scant information, the best tactic is often clinging on to what has worked best in the past. At the time, the common-sense solution was to assume that every living creature – including those as yet unborn – had been created by God right at the very beginning. According to the Bible, around 6,000 years ago the world and its inhabitants were formed exactly as they are now; since then, there have been neither extinctions nor new species – even fossils have always been present. For people immersed in such beliefs, it seemed plausible that future beings had originally been packed one inside another like a set of Russian dolls.

To convince his prestigious audience that preformation was the right answer, the Dutch anatomist Jan Swammerdam peeled back the skin of a silkworm to reveal what appeared to be a folded-up version of the future moth inside. The French priest Nicolas Malebranche coined the perfect rejoinder for silencing sceptics:

‘We cannot measure the power of God with our weak imagination, and we do not know the reasons He may have had in the construction of His work.’

It was common knowledge that many creatures emerge from eggs, the obvious candidates for encapsulating future generations. In a Christian interpretation, the population of the world had incipiently existed since God’s creation in the Garden of Eden, because every human being had descended from Eve’s internal set of Russian dolls. Theologically, this view confirmed the teaching of Jesus that all men are brothers, stained by original sin. Politically, it could be adapted to reinforce the notion that people are predestined for a particular station in life: kings and queens can only emerge from royal lineages, whereas generations of servants are conveniently encased one inside another, with no possibility of upward mobility.

Believing is seeing

Preformation theories flourished well into the second half of the 18th century, when their most acclaimed supporter was Lazzaro Spallanzani, now celebrated for proving that spontaneous generation cannot happen. The standard example involves boiled broth: securely sealed inside a flask, it will remain sterile and inert forever, unless miniscule life organisms are allowed in from the outside air. In another experiment, Spallanzani sewed tiny taffeta shorts onto male frogs. When no babies resulted from their contact with females, he claimed it as proof that an egg’s preformed individual can only be stimulated into development by unfiltered semen.

In retrospect, it seems strange that Spallanzani used his frog experiment to support preformation. The evidence of your own eyes is convincing, but what you see can depend on how you look and what you already believe. In 1768, when Spallanzani claimed to have spotted a tiny tadpole curled up inside an unfertilised frog’s egg, some of Europe’s most influential researchers agreed that preformation had been confirmed. By then, he had acquired a stellar reputation as a microscopist – but building better instruments did not necessarily mean seeing more clearly.

During the previous 100 years, rival researchers had been peering through their lenses to reach different conclusions. In contrast with ovists such as Spallanzani, supporters of spermism believed that offspring formed at the Creation were carried down through the generations by male agency; for them, the woman’s role was simply to provide a nurturing environment. One of its most famous protagonists was the Dutch researcher Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who invented a small but fiddly microscope with unprecedented magnification. By examining his own semen, he discovered that it contained tiny ‘animalcules’ (later labelled spermatozoa).

From then on, ovists no longer monopolised pontifications about reproduction. After collecting further evidence from other animals, van Leeuwenhoek articulated a theory that appealed to male egos: ‘The foetus proceeds only from the male semen and the female only serves to feed and develop it.’ Even though his explanations of how that process might actually work remained rather incoherent, theologians backed him up, eagerly using his findings as evidence that ‘all the Plants and all the Animals … have been formed at the origin of the World by the Almighty Creator within the first of each respective kind’.

Life is but a dream

If this were a mythological battle, the ovists would have roundly defeated the spermists to reign supreme for ever after. But this is a tale about real life, where outcomes are rarely so clear-cut and science does not progress ineluctably upwards and onwards.

Spermism proved a relatively short-lived belief, vanquished not only by scientific scepticism but also by a powerful theological argument: God’s opposition to waste. How could God have created so much potential life only to throw it away? In Genesis, Onan dies because ‘he spilled his seed on the ground’. For centuries, this condemnation underpinned objections to masturbation, but it also provided biblical backup against the spermists’ insistence that preformation is effected by the male line.

If science really did proceed rationally, egg-based theories of preformation would have been eliminated by the absence of visible evidence, but they survived for decades as a bulwark against atheism, as proof that God was in charge of creation. In a sense, they reappeared in the 20th century after Francis Crick and James Watson claimed to have found the secret of life in a double helix. Many modern researchers disagree with their deterministic vision, arguing that a twisted chain of molecules is just a chemical version of preformation. The relatively recent approach of epigenetics is opening up new possibilities, but the riddles of reproduction remain unsolved.

Patricia Fara is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. Her most recent book is Life after Gravity: The London Career of Isaac Newton (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Source: History Today Feed