How Father Christmas Found his Reindeer - 11 minutes read

When I was a child, I could never have imagined Santa Claus without his reindeer. They were as much a part of his character as his bushy white beard, his red coat, or his sack of presents. After all, how else could he have got around if they hadn’t been there to pull his sleigh? Before going to bed on Christmas Eve, I’d take care to leave a carrot for Rudolph – and the next morning, I’d swear blind that I’d heard hooves clattering on the roof before I fell asleep. Little did I suspect how recently Santa had come by his reindeer – or how much their night-time sleigh ride owed to religious reform, migration and cultural exchange.

Saint Nick

Originally, Santa Claus had nothing to do with reindeer – or with Christmas. His story begins with St Nicholas, a fourth-century bishop of Myra, in modern Turkey. Although little is known about his life, the few hagiographical works which have come down to us all testify to his love of children and his generosity. According to Michael the Archimandrite, he was once told about a man who had lost all his money and was unable to provide dowries for his three daughters. Since this would have prevented them from getting married, they might have had to become prostitutes to support themselves. Naturally, St Nicholas was anxious to help, but did not want to shame them by giving alms openly. To avoid this, he crept up to their house late at night and threw a purse of gold through the window. When their astonished father found it the next morning, he immediately sought a husband for the eldest. The next night, St Nicholas did the same again. On the third night, however, the father stayed awake and caught St Nicholas in the act. Falling to his knees, he hailed the saint as his family’s saviour, only for St Nicholas to raise him to his feet and beg him not to tell a soul about the blessings he had received.

Because of such acts of generosity, St Nicholas’ feast day (6 December) was later celebrated with the exchange of presents. In 12th-century France nuns are said to have left fruit, nuts and treats outside the houses of poor children. At around the same date, St Nicholas was also transformed into a magical bringer of gifts. Particularly in Dutch-speaking regions, ‘Sinterklass’ would sneak into poor peoples’ houses at night and leave a few coins or a little present in their shoes.

For obvious reasons, he was portrayed as a bishop, with long, brightly coloured vestments, a mitre and a beard. He was also said to travel through the sky and to have an uncanny knack for remaining unseen. At times, St Nicholas was even associated with certain animals. In the Netherlands there was a tradition of leaving hay for his horses, in some parts of Germany he still rides a horse, in eastern France he keeps his presents in baskets carried by a donkey and in Italy he is often accompanied by a jovial ass.

But of reindeer, there was no sign – and with good cause. Although they were once common throughout Europe, their habitat receded at the end of the last ice age, to the point that they were mostly confined to northern Scandinavia and the Ural mountains. Other than a few brief references in Aristotle, Theophrastus, Julius Caesar and Pliny, there is little written testimony before 1533, when Gustav I of Sweden sent a gift of ten reindeer to Albert I of Prussia – and absolutely nothing to connect them with a fourth-century bishop from Asia Minor.

Reform

The Reformation changed everything. Because of Martin Luther’s insistence that Jesus Christ is the only mediator between God and man, most early Protestants rejected the Catholic cult of saints out of hand. Although they were happy to recognise that those who had led uncommonly holy lives should be held up as examples of Christian virtue, they refused to believe that anyone could intercede with God on another’s behalf and regarded the veneration of saints as a form of idolatry. Any form of worship or celebration that seemed to point towards the human instead of the divine was hence discouraged, if not actively forbidden.

This spelled trouble for St Nicholas. While he was seen as sufficiently virtuous to be included in the Lutheran liturgical calendar, the revelry with which his feast was traditionally celebrated was definitely suspect. No doubt it would have been easiest just to ban it, but Luther was shrewd enough to realise that gift-giving had become so central to the festive season that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to stamp it out. To overcome this problem, Luther simply transferred the practice to Christmas Day itself and focused attention on Christ, God’s original gift to mankind, instead. Although this did not necessarily stop people from celebrating the day in style, it did mean that, from then on, presents would be brought not by St Nicholas, but by the ‘Christkind’ or ‘Christkindl’ (‘Christ-child’) who was usually portrayed as a brightly arrayed infant, with wings and a halo.

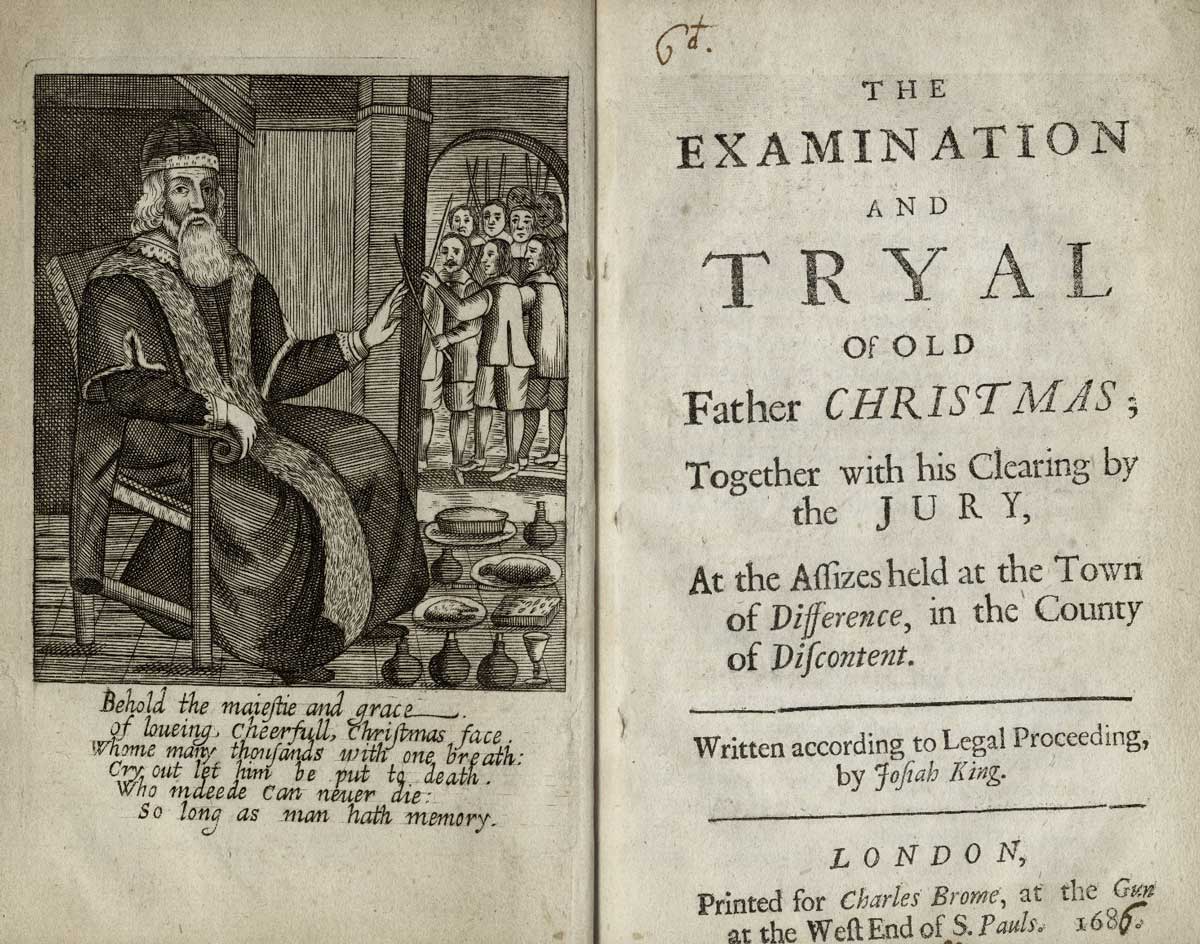

Even in some Protestant areas, however, the legacy of St Nicholas lived on, albeit in a modified form. In England, a ‘Father Christmas’ figure was already well established by the reign of Elizabeth I. Clearly modelled after St Nicholas, he was held to embody the spirit of Christmas – and, as an engraving from Josiah King’s The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas (1686) suggests, was generally pictured as a burly man, with a heavy, fur-lined coat, a pointed, mitre-like hat and a beard. In some areas of Belgium and France ‘de Kerstman’ or ‘Père Noël’ came to play a similar role. But he still didn’t have any reindeer.

Migration

For many years, St Nicholas and ‘Father Christmas’ continued to exist as separate traditions. Though in some regions, such as Alsace and parts of the Netherlands, where Catholics and Protestants lived in close proximity, each figure had a certain role to play in festive celebrations and confessional divides generally ensured that they remained distinct.

By the late 18th century, however, demographic changes on the other side of the world caused the two to coalesce. Following the War of Independence, the United States experienced a dramatic rise in immigration. Most of the new arrivals came from Britain, Germany and the Netherlands – and the majority were either Protestants or nonconformists. It is estimated that by 1780 more than a quarter of New York’s population traced their origins to the Low Countries, while New Jersey, Delaware and Pennsylvania had large German-speaking minorities. After 1790 the influx slowed a little, due largely to the disruption of the Napoleonic Wars, but by the 1830s immigration had begun to rise again. Over the next two decades large numbers of Irish Catholics came.

At first, different migrant groups all seem to have celebrated Christmas in their own way. Whereas some of the more austere nonconformists tended to shun overly ‘pagan’ celebrations, others – particularly the Dutch in New York – indulged in tremendous revelry, with lots of drunken fun and sexual delinquency. More importantly, where the tradition of gift-giving was preserved, there was no single figure who brought children their presents – and there was a marked lack of clarity over when he came.

But in the melting pot of the early United States, Christmas traditions inevitably got mixed together. Practices and personalities gradually fused and long-separated ideas were recombined. Though much of this may have been unconscious, it may have been encouraged by efforts to contain some communities’ excesses. First, the Dutch ‘Sinterklass’ was ‘translated’ into English to give ‘Santa Claus’. This appeared for the first time in a report in the New York Gazette on 26 December 1773. Then, a few decades later, Santa Claus was identified with the English ‘spirit of Christmas’ and shorn of his association with the Dutch community’s fondness for raucous celebrations. At times, it is true, he still went by one of his old names or by mangled versions of a European analogue (e.g. Kris Kringle for Christkindl) but, in his attributes and manner, he was now recognisable as something close to the Santa we know today.

He seems to have made his debut in Knickerbocker’s History of New York (1809) by Washington Irving. A collection of satirical sketches, this portrayed him as a fat Dutchman, sporting ‘a low, broad-brimmed hat, a huge pair of Flemish trunk hose, and a long pipe’ and riding across the sky in a ‘wagon’ full of presents. But not until the publication of The Children’s Friend: A New Year’s Present to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve in New York in 1821 did a reindeer come into play. One of the poems in this curious little book began with the following, fateful verse:

Old SANTECLAUS with much delight

His reindeer drives this frosty night,

O’r chimney tops, and tracts of snow,

To bring his yearly gifts to you.

What prompted the anonymous author to introduce a reindeer is a puzzle. One possibility is that it was simply down to the weather. Although there was always a chance of snow at Christmas, the previous decade had seen some of the coldest weather on record. On 24 December 1811, Noah Webster reported that more than a foot of snow had fallen in New Haven and in 1816 (the ‘Year without a Summer’), snow had even fallen in June. The winter of 1820-21 was especially harsh. In New York the Hudson froze over and the city was blanketed in heavy snow. Most ordinary forms of transport became impossible, but, as the local historian James Macauley later recalled, the ‘[s]leighing was pretty good’. While there is no record of reindeer being used to pull any sleighs in New York, anyone interested in Santa could have been forgiven for thinking of the animals that were used to pull them in stereotypically ‘snowy’ regions. Alaska would have been an obvious point of reference. Although it was not yet an American territory, the use of reindeer by indigenous peoples was already well known – and it would have been a small step to hitch them to Santa’s ride.

Enter Rudolph

The number of reindeer soon grew. On 23 December 1823, the poem ‘A Visit from St Nicholas’ (also known as ‘The Night Before Christmas’) appeared in the New York Sentinel. Later attributed to Clement Charles Moore, this described a chubby, if diminutive, St Nicholas riding across the sky on a sleigh pulled by eight ‘tiny reindeer’ called Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder and Blixem. Later, two more were added. In L. Frank Baum’s story, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus (1902), Santa’s companions were arranged into five pairs: Racer and Pacer, Fearless and Peerless, Flossie and Gossie, Ready and Steady, and Feckless and Speckless.

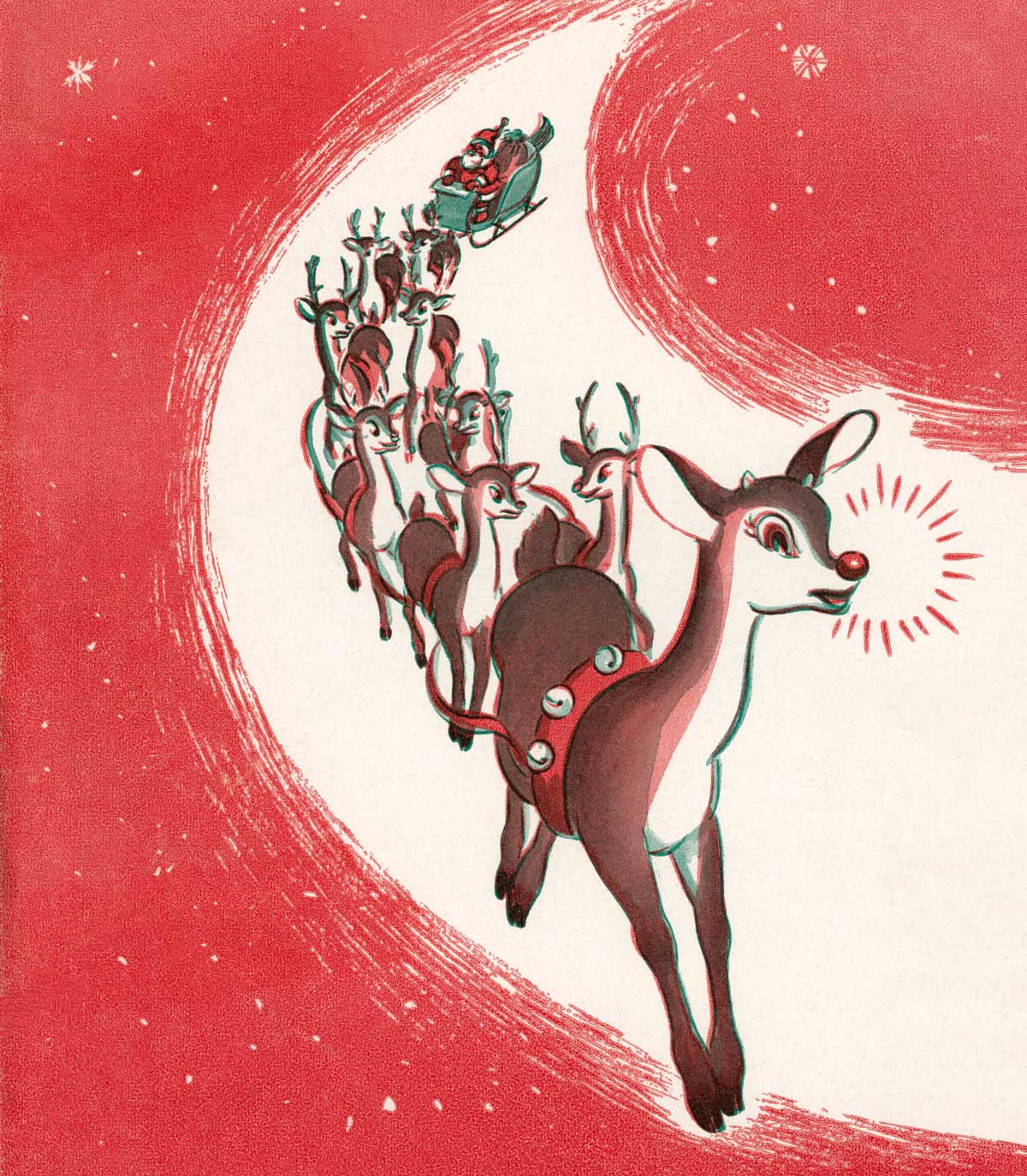

At about this time, Santa Claus was re-exported back to Europe, where he gradually merged into the figures whose attributes he had been given. He also took his reindeer with him. But not until much later did Rudolph join his troupe. In 1939 Montgomery Ward department stores commissioned Robert L. May to write a story book which could be given to children visiting their branches over the Christmas period. In May’s tale, Rudolph was shunned by the other reindeer because of his bright red nose. But one year, when fog threatens the delivery of Christmas presents, Santa spots it glowing in the gloom and asks him to light the way as the troupe’s ninth member. Though initially intended as a local give-away, May’s story proved so popular that it later inspired a cartoon (1948), a song (1949) – and no end of films and books.

Since then, Santa’s reindeer have been re-imagined countless times. They have been renamed, pared down, beefed up and altered in almost every way. But it is now impossible to think of Santa without them. And if you listen carefully this Christmas Eve, you might just hear them on your roof, too.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance of Warwick University. His latest book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, is now available in paperback.

Source: History Today Feed