Crossing Oceans | History Today - 6 minutes read

Considering their origins, cloves – dried blossom buds of a Southeast Asian tree, Syzygium aromaticum – appear remarkably frequently in medieval literature. Dante mentions them in the Inferno, where the decadent use of cloves in roasting meats has apparently condemned Niccolò Bonsignori to Hell. In one of the stories in Boccaccio’s Decameron, a female con artist uses clove-scented soap to trick a mark into believing her to be a noblewoman and thus into helping her out with a loan. Cloves even feature in tales of the Holy Grail; in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, they are said to cover up the smell of the Fisher King’s wounds. Chaucer mentions both clove and nutmeg in his Tale of Sir Thopas, one of The Canterbury Tales, using them to fashion a parodic image of a fantasy land from a chivalric romance. In medieval Arabic fantasies (so-called ‘aja’ib literature) we find descriptions of similarly impossible places, where clove trees grow alongside date palms, sandalwood shrubs and pepper bushes. In Indian stories, like the ninth-century Prakrit tale Lilavai, cloves feature alongside cardamom and other spices as emblems of South India – although they did not in fact grow there until the 19th century.

All the cloves in the medieval world came from five tiny islands in what is now the far east of Indonesia, closer to New Guinea and Micronesia than to India or China (let alone the Middle East or Europe). These islands – Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Bacan, known collectively as Maluku and in English as the Moluccas – lie in a north south line straddling the equator just west of the larger island of Halmahera. All are volcanically active. When the first Portuguese expedition arrived in 1512, the islands of Ternate and Tidore, each not much more than a volcanic cone with a strip of fertile habitable land surrounding it, were home to two rival Islamic sultanates. Islam had arrived recently, almost certainly in connection with the clove trade, and did not have deep roots. Tomé Pires, a Portuguese apothecary writing about Southeast Asia in around 1515, says that ‘many [in the Moluccas] are Muslims without having been circumcised, and the Muslims are not many; the heathens are three parts out of four, or more’.

Contrary to the popular conception of the pre-colonial spice trade as dominated by Sinbad-esque Arabian seamen, there are few direct indications in the Arabic sources that medieval Middle Eastern sailors went as far as Maluku, or knew the islands there by name. There are, however, descriptions of eastern Indonesian islands in Chinese writings – such as Wang Dayuan’s c.1339 account of the Banda Islands, where all the world’s nutmeg then grew – and several references to Maluku can be found in 14th- and 15th-century texts in Old Javanese and Old Sundanese, two languages of the island of Java, now also in Indonesia. (Curiously, cloves seldom appear in pre-16th-century literature from the archipelago.) The cloves that ended up on the international market probably began their journeys in local Moluccan vessels, taking two weeks to arrive at ports in Java, from where they could be sent in all directions.

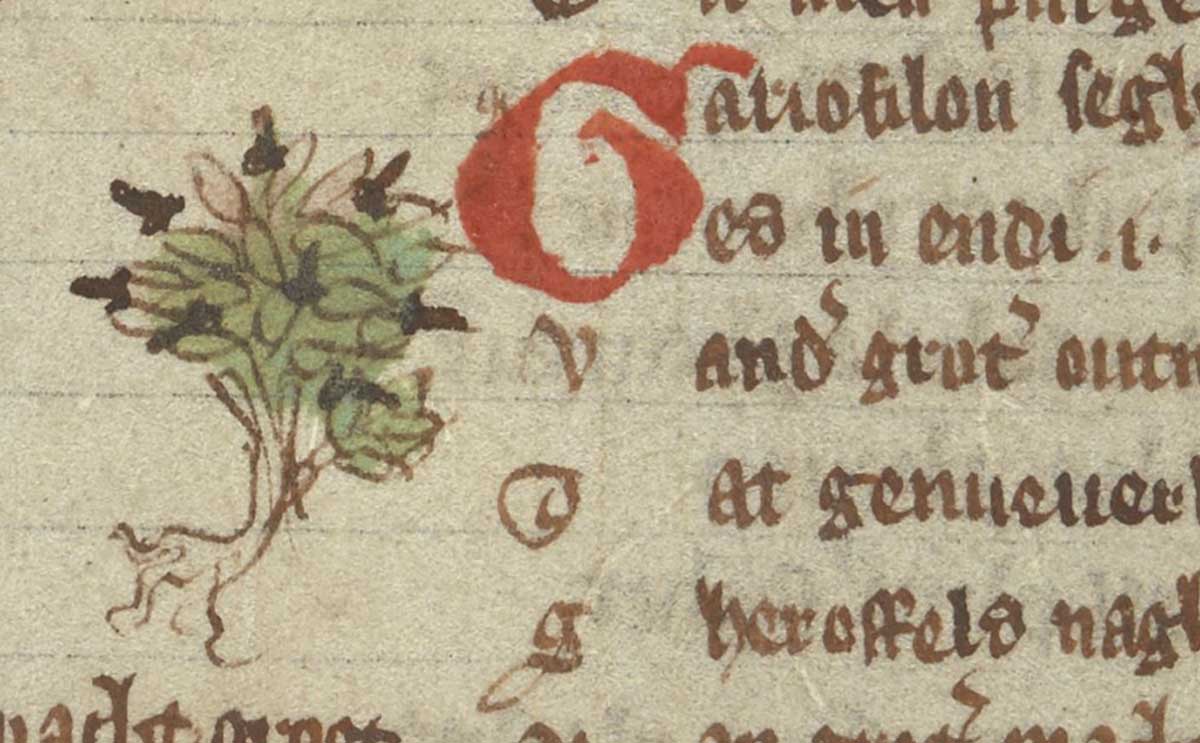

Cloves look like little nails and, indeed, the words for ‘clove’ in many languages make reference to the similarity. This equation is found in Old East Slavic (or Old Russian – gvozdíka ‘little nail’), Middle Danish (gørfærs naghlæ ‘clove nails’) and Chinese (dīng xiāng ‘nail aromatic’) – although the poets Cao Zhi (192-232) and Du Fu (712-770) both referred to cloves by their alternative names, ‘chicken/fragrant tongue’. The English clove is ultimately from Latin clavus ‘nail’, as are words for ‘clove’ in other Romance languages.

Cloves were used in kitchens throughout Afro-Eurasia in the Middle Ages, appearing frequently in cookery books written before the 16th century in Arabic, Chinese and even Icelandic. Many recipes in the Middle English Forme of Cury (1390) call for cloves – whole or powdered – alongside other warm spices such as cinnamon and ginger. The quantities could be enormous: account books for the 1475 wedding of Duke George of Bayern-Landshut and Hedwig (Jadwiga) Jagiellon, a Polish princess, in Landshut, Bavaria, tell us that 105 pounds of cloves (Nägell, another ‘nail’ word) were purchased for the reception. Cloves could also be used to flavour betel quids – small, mildly narcotic packages, wrapped in betel leaves and chewed as a stimulant – as is described by the 12th-century Chinese administrator Fan Chengda.

The role of cloves in medicine is also well documented. The tenth-century Baghdadi author Ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq reports that cloves ‘are hot and dry’ and that they ‘strengthen stomach and heart’, features mentioned in medieval medical texts across Afro-Eurasia. Traditional Chinese medicine still maintains that cloves are good for stomach problems. In Bald’s Leechbook, a ninth-century Old English medical compendium, we are told of a ‘southern herb’ called næglæs (‘nails’), said to be good for ‘internal swellings’. (This may be the oldest reference to cloves in English.) The 14th-century Egyptian encyclopaedist al-Nuwayri includes cloves, alongside nutmeg, Chinese cinnamon and cardamom, in a recipe for a ‘jam that strengthens sexual appetite and the stomach’. Cloves were even employed in veterinary medicine, demonstrating if nothing else that these spices were valued for their medicinal properties and not just their taste. The Libro de la caza de las aves (‘book on hunting with birds’), a falconry manual written by the Spanish knight Pedro López de Ayala in 1386, suggests treating indigestion in hunting falcons with a mix of sugar and spices, including cloves, stuffed inside a chicken’s heart.

We cannot be certain that this recipe was ever used, although López de Ayala suggests that it was – in which case, in the 14th century, dried blossom buds, grown and harvested on equatorial volcanic islands in what is now Indonesia, were shipped across the Banda Sea and the Indian Ocean, up the Red Sea and across the Mediterranean, passing through many merchants’ hands and several ships’ hulls, where they must have ended their journeys being digested and excreted by a Spanish noble’s sick bird. There can be few more vivid illustrations of the peculiarly interconnected nature of the medieval world than this.

Alex West is an independent scholar with a PhD from Leiden University.

Source: History Today Feed