You and Whose Army? | History Today - 5 minutes read

Henry Marten has the distinction of being the only member of the Long Parliament who can be identified as a republican before the outbreak of the First English Civil War in 1642. He remained true to his principles and, in 1649, was one of the 135 commissioners appointed to the High Court of Justice to try Charles I for treason against the people of England. His signature can be found on the king’s death warrant, along with those of 58 of his fellow judges. As Marten and Oliver Cromwell anxiously waited to see who would be bold enough to sign with them, they indulged in horseplay, smearing each other’s face with ink. The two men would later fall out and Cromwell attacked Marten in the House of Commons for drunkenness and fornication. Earlier Charles I had allegedly described Marten as an ‘ugly Rascall’ and ‘that whore-master’.

In Regicide, John Worthen counters these assessments. Marten’s louche reputation was based on his adulterous relationship with Mary Ward. The couple lived together openly from the 1640s until Marten’s incarceration as a regicide in the Tower of London in 1660. In 1662 his letters to Mary from the Tower were published with the fanciful title of Coll. Henry Marten’s Familiar Letters to his Lady of Delight.

Regicide is based on this chaotic and unauthorised publication. Worthen finds Marten to have been an attractive and sympathetic character, with his concern for Mary’s welfare shining through at all times. He was also a doting father to their three illegitimate daughters, Peggy, Sarah and Henrietta, the last also curiously known as Bacon-hog. During the period that the letters were written the threat of a dreadful execution by hanging, drawing and quartering was omnipresent in Marten’s mind. In the event he remained in prison until his death in 1680.

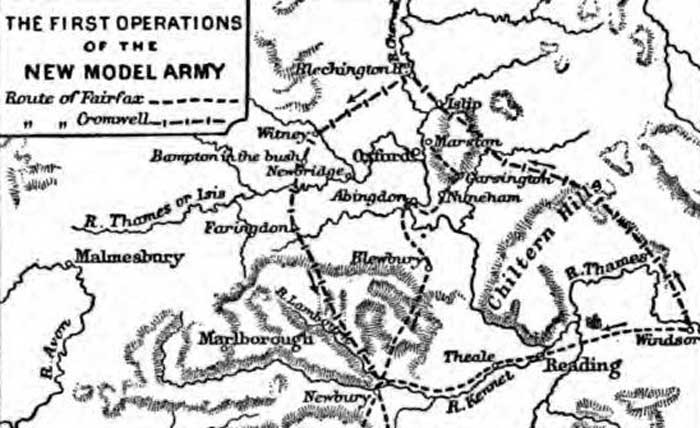

Worthen is right in his assessment that Marten deserves to be better known; his book provides both a brief introduction to Civil War politics and an insight into the preoccupations of a man under the sentence of death. In contrast Ian Gentles’ The New Model Army is a richly detailed and authoritative survey of Parliament’s formidable army formed in 1645 and disbanded at the Restoration. It is the second edition of a book first published in 1992, which covered the period to 1653. This new work includes the history of the army to 1660 and incorporates the research of Civil War historians published during the past three decades.

Ian Gentles has not changed his view of the New Model Army, which he characterises as promoting radical political ideologies and forms of religious dissent, which would lead to conflict and even mutinies within the army. He emphasises that the army was protean and at times recruited former royalists and unwilling conscripts. Unsurprisingly, these troops were the most likely to desert or be slimmed down when funding was short. Starting with a force of 21,000 men in 1645, the army mushroomed to 63,000 men in 1659 including forces in England, Ireland, Scotland, Jamaica and Flanders.

The core of the Parliament’s army was a remarkably cohesive force, claiming victory over the royalists at Naseby in 1645, over the Scots at Dunbar in 1650, the ragged troops of Charles II at Worcester in 1651 and occupying Ireland after a series of bloody sieges. From 1647 the army was inspired by the agenda of the Levellers, the first political party in England, who opposed monarchy, demanded law reform and promoted greater political participation among the people of England. It was instrumental in bringing Charles I to trial, remained largely loyal to Oliver Cromwell and, paradoxically, facilitated George Monck in his plans to restore Charles II.

Political interventions by the army were preceded by intensive days of religious observances and spiritual fasting. As a result of this shared religious consciousness the New Model Army ‘enjoyed markedly higher morale than most armies of the 17th century’. Sermons by regimental chaplains routinely lasted for two hours or more and both officers and the soldiery frequently practised lay preaching. Cromwell and other officers met for three days of prayer and fasting at Windsor in April 1648 before resolving to renew the fighting.

The radical religious and political activities of the army and the execution of the king led to internal conflicts and to the withdrawal from public life of the army’s first commander-in-chief, Thomas Fairfax. His place was taken by Cromwell, whose care for the men under his command was reflected in their loyalty to him. Cromwell’s military success can be traced in part to his refusal to take rushed action. On his way to the Battle of Preston in 1648 Cromwell stopped for several days to await the arrival of boots and stockings for his men from Northampton.

Nevertheless, arrears of pay were a perennial problem and at times soldiers demanded free quarter and plunder. The collapse of the Republic after Cromwell’s death in 1658, combined with the ‘pathetic and indecisive leadership’ of the army, finally played into Monck’s secretive manoeuvring to bring back the monarchy. The New Model Army has been widely admired as a fighting force and as a political player, but, as Gentles argues, it also left a legacy of civilian resistance to standing armies and an enduring dislike of Puritanism.

Regicide: The Trials of Henry Marten

John Worthen

Haus 244pp £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

The New Model Army: Agent of Revolution

Ian Gentles

Yale University Press 386pp £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Jackie Eales is Professor of Early Modern History at Canterbury Christ Church University.

Source: History Today Feed