Rivers of Silver, Cities of Gold - 5 minutes read

When Elizabeth Fulhame embarked upon a series of experiments exploring the colouring of textiles, she began a project that would lead her to invent the process of photoreduction, introduce the concept of catalysis and lay the foundations for photography. That all this would be presented within a single volume, the only work Fulhame would ever publish, makes her story and her current obscurity all the more intriguing.

Perhaps Fulhame anticipated this lack of appreciation when she wrote in the preface to her work:

For some are so ignorant, that they grow sullen and silent, and are chilled with horror at the sight of anything that nears the semblance of learning, in whatever shape it may appear; and should be the spectre appear in the shape of a woman, the pangs which they suffer are truly dismal.

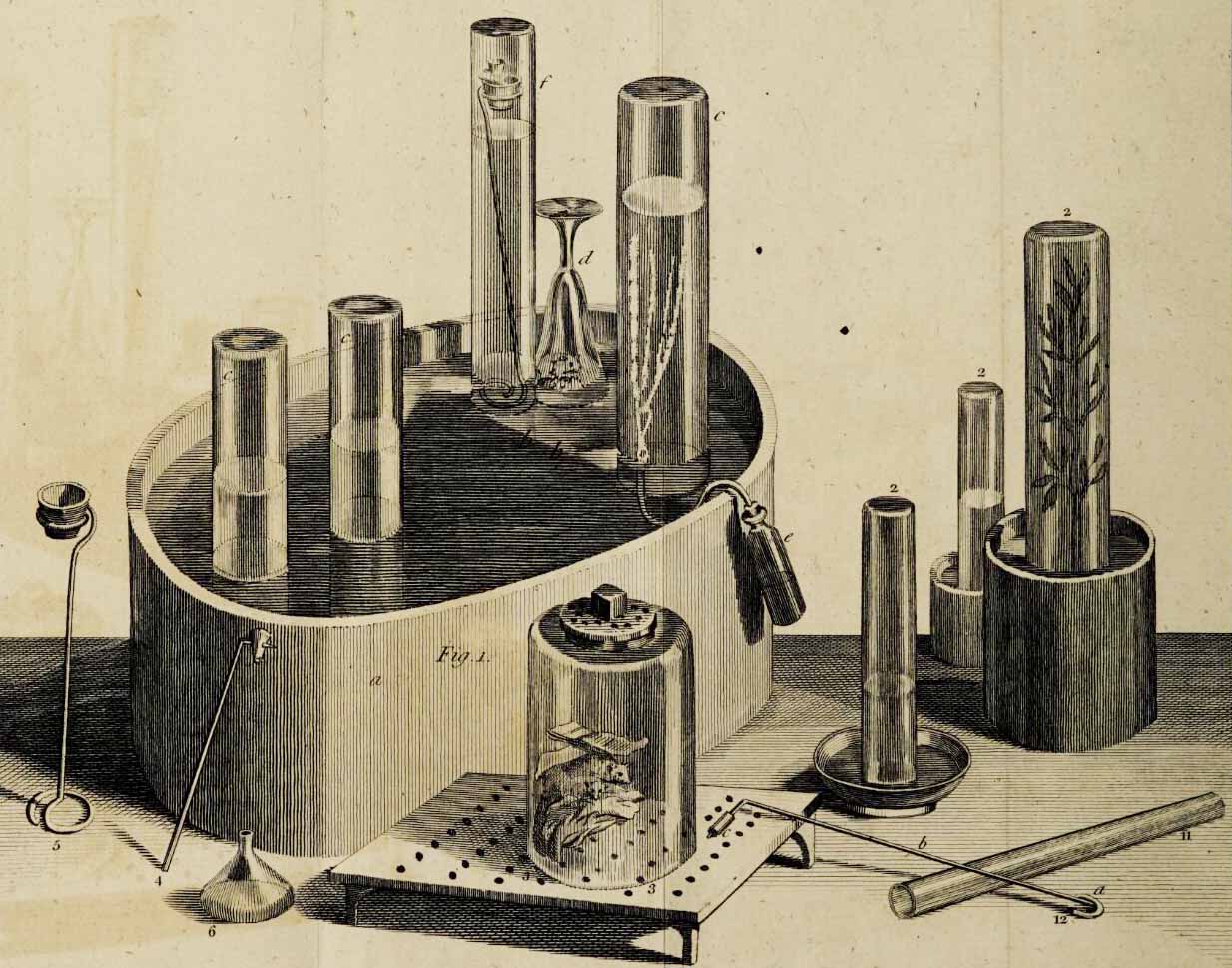

We possess less than the bare bones of a biography of Fulhame. It is believed she was Scottish and married to an Irish-born doctor, who had studied at the University of Edinburgh. In 1780, she had the idea of colouring cloth using the action of light, although, when she mentioned it to her husband and some friends, they ‘deemed it improbable’. Undaunted, she began an exhaustive series of experiments in which she investigated the reduction of metal salts and the images and colours that formed as a result on cloth. Her basic approach was to expose metallic salts in various states – in aqueous solution, in the dry state and sometimes in ether or alcohol solution – to light, thus introducing the process of photoreduction. Her results were noted in an exhaustive set of observations that stretched to almost 200 pages. This led to several findings: that certain reactions could reduce metal salts to pure metals; that metals in aqueous solutions could be reduced at room temperature (an observation that would offer an alternative to smelting at high temperatures) and that water accelerates certain oxidisations (and is regenerated when the reaction is complete). Without actually naming it, Fulhame had introduced the concept of catalysis, the idea of a substance being used to speed up a chemical reaction without being consumed by it, a process now at the heart of everything from refining oil and producing fertilisers, food and medicine to scrubbing air of pollutants.

Beyond the aesthetic appeal of the colouring and patterning of textiles, Fulhame recognised an immediate use for her work, in painting and in the production of maps:

I have applied it to some maps, the rivers of which I represented in silver, and the cities in gold. The rivers appearing as it were in silver streams, have a most pleasing effect on the sight, and relieve the eye of that painful search for the course and origin of rivers.

Photo-imaging also pointed the way to photography. Indeed, John Herschel, influenced by her work, referred to Fulhame in his landmark lecture to the Royal Academy in 1839, which helped prepare the world for Daguerre, Fox Talbot and the freezing of time through the photographic image.

Yet Fulhame almost did not publish her findings, such was the lack of enthusiasm for her project. After meeting with a supportive Joseph Priestley in 1793, however, she decided to press on and her Essay on Combustion with a view to a New Art of Dying and Painting wherein the Phlogistic and Antiphlogistic Hypotheses are Proved Erroneous was published in 1794.

Over the years, there were a few references to her Essay in publications such as Gentleman’s Magazine (‘An essay on combustion, by a lady!’), glowing reviews and analyses from eminent chemists and eventual publication in Germany in 1798 and the US in 1810. Widespread appreciation of her work seems to have eluded her, however.

Not all Fulhame’s findings were correct: she erroneously believed, for example, that water was required for all reductions. Nevertheless, her work constituted a bedrock of chemical research for those who cared to look and were not put off by the spectre of her femininity.

The Essay was also a significant early work of feminism thanks to an impassioned preface, which offered her work as a ‘beacon to future mariners’ and promised that its author would ‘hold the helm with becoming fortitude against the storm raised by ignorance, petulant arrogance, and privileged dullness’.

The specificity of some of the observations in the preface suggest that Fulhame had already personally experienced resistance to her work in the form of ‘innuendoes, nods, whispers, sneers, grins, satanic smiles, and witticisms uttered’, but she remained defiant, ‘for this little bark of mine has weathered many a storm’.

At the end of her Essay, Fulhame wrote:

Nature is always the same, and maintains her equilibrium by preserving the same quantities of air and water on the surface of the globe; for as fast as these are consumed in the various processes of combustion, equal quantities are formed.

Her use of ‘equilibrium’ here is remarkably modern, describing an environmental balance in broad alignment with Priestley’s first tentative musings on air ‘cleaned’ by vegetation (he had noted a sprig of mint absorbing carbon dioxide and producing oxygen), which were the loose beginnings of a worldview of interconnected and mutually supportive ecosystems.

Perhaps this helps us place Fulhame in her intellectual context – on the progressive edges of science and sexual politics, a courageous thinker who might be found in the enlightened circles of Priestley, Benjamin Franklin and Mary Wollstonecraft. It is not much of a clue, but if followed it might help us to catch sight once more of this singular and inspirational beacon.

Irfan Shah is a writer, researcher and filmmaker from Leeds, interested in the history of photography.