For the Love of Manuscripts - 5 minutes read

The Posthumous Papers of the Manuscripts Club is a logical sequel to Christopher de Hamel’s Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts (2016), in which he introduced readers to some of the most famous handmade books of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In this new book he turns his attention to the important question of how such manuscripts have survived the intervening centuries since they were made. The book examines the lives of 11 men and one woman whose actions have played a major part in shaping the fates of medieval books and determining both what survives and where the manuscripts are to be found today.

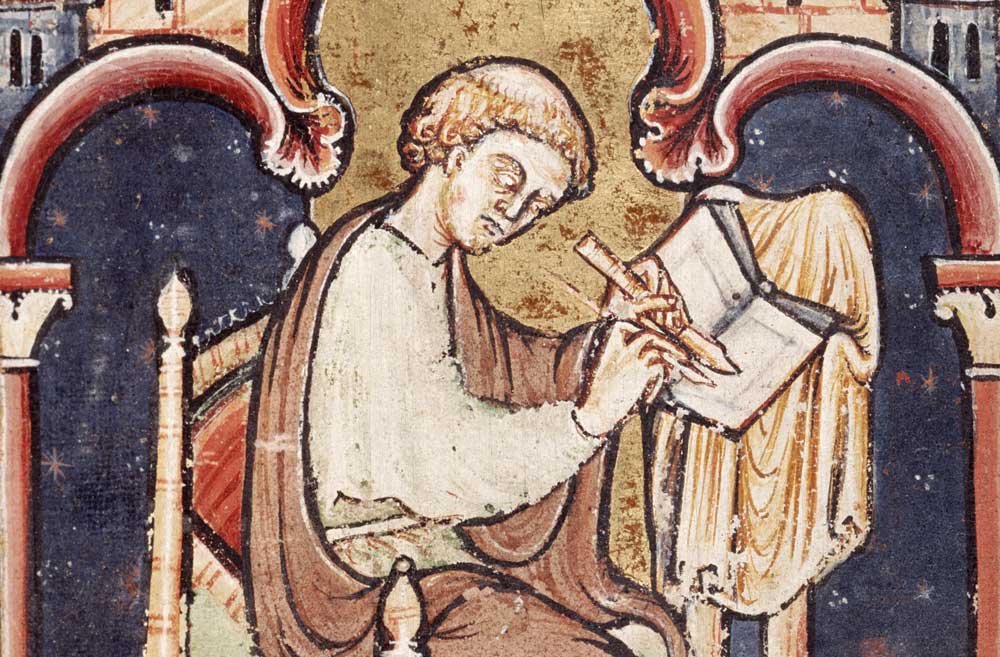

The people selected for de Hamel’s imaginary manuscripts club, inspired by real groups such as the Roxburghe Club and the Grolier Club, are drawn from eight centuries. The subjects have been selected carefully to showcase different kinds of engagements with manuscripts, beginning with the 12th-century monk, Saint Anselm, and the culture of copying and distributing manuscripts that he promoted at the abbey of Le Bec in Normandy and later at Canterbury where he was archbishop. De Hamel imagines meeting his subjects, drawing on surviving places as well as manuscripts. There is, of course, much more evidence for the more recent subjects, so these imagined meetings become rather less speculative as the book progresses. The central premise, however, is that these people who lived in very different times and places would find common ground with de Hamel, the reader and each other in their shared love of manuscripts.

The members of de Hamel’s fictional club are a deliberately diverse group. After the monk Anselm, the reader is introduced to Jean, Duc de Berry (1340-1416), one of the richest men of his time, the Florentine bookseller Vespasiano da Bisticci (c.1422-98) and the artist Simon Bening (c.1484-1561). From this point the interactions with medieval manuscripts cease to be those of creation and shift instead to collecting and preservation. The next member of the club, Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631), is probably best known as the creator of an enormous library partially destroyed by fire in 1731, with what survived now forming a major part of the collections of the British Library. Cotton’s interests, as well as the actions of those who rescued books from the fire, have therefore played a significant role in shaping the material available to modern scholars.

The chapter on Rabbi David Oppenheim (1664-1736) is particularly valuable to those of us familiar with Latin manuscripts, but not Hebrew ones, as a reminder of the challenges facing those beginning to work with unfamiliar material, which has been one major reason for the disposal of old manuscripts. In this study de Hamel is accompanied by an expert, Brian Deutsch, who not only translates the Hebrew for him, but gives the reader insights into a different set of values for manuscripts, where old does not necessarily mean valuable and instead originality and rarity of the text are key.

For de Hamel, an enthusiasm for books can compensate for many other failings. Supremely confident in his own judgements, Abbé Jean-Joseph Rive (1730-91) emerges as someone who would be a challenging club member and his story illustrates how collecting tastes, as well as scholarly opinions, have changed over the last 300 years. Similarly, Sir Frederic Madden (1801-73) spent much of his career as keeper of manuscripts at the British Museum feuding with the head of printed books, while Constantine Simonides (1824-90) both sold and forged manuscripts, providing us with valuable insights into what the scholars and collectors of the 19th century most desired (even when it did not survive). Sir Thomas Phillipps, who amassed the largest private collection of manuscripts and was another man renowned for being difficult to deal with, could easily have had his own case study, but instead appears repeatedly in the lives of others.

The studies of Theodor Mommsen (1817-1903) and Sydney Cockerell (1867-1962) trace the increasing professionalisation of the study and care of manuscripts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with Mommsen the only person (to date) to have been awarded a Nobel Prize for his work on manuscripts. Trained by the collectors John Ruskin and William Morris, Cockerell played a key role advising English collectors of illuminated manuscripts before joining the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. In addition, he built his own collection before releasing the books back onto the market in his old age. The book concludes with Belle da Costa Greene (1879-1950), underlining how white and male the history and historiography of collecting has been. Other women do appear throughout the book, notably Simon Bening’s daughters, one of whom became an artist. Nevertheless, much remains to be done as we seek to understand the contributions of those who supported and facilitated the members of this manuscript club. De Hamel’s book is a valuable starting point.

The text is engagingly written, inviting the reader to follow the author on his travels to study these people in their own environments. Throughout his career de Hamel has done an immense amount to make these complex and fascinating artefacts accessible to a wide audience. At times his imaginative leaps demonstrate the gaps between our contemporary questions and the nature of historical records. For example, suggesting medical diagnoses for the people of the past can only ever be extremely speculative. Nevertheless, although the book wears its thorough research lightly, the interested reader will find much valuable information in the endnotes. The epilogue indicates that membership of de Hamel’s club is not restricted to 12; many other characters appear, who may become the subject of a study in their own right. The club is open.

The Posthumous Papers of the Manuscripts Club

Christopher de Hamel

Allen Lane 624pp £40

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Laura Cleaver is Senior Lecturer in Manuscript Studies at the Institute of English Studies.

Source: History Today Feed