An Acceptable Hero | History Today - 5 minutes read

On 30 November 2021 Josephine Baker, the African-American performer who took French citizenship, was inducted into the Pantheon. The Pantheon is France’s secular equivalent to Westminster Abbey, the hallowed home of the country’s honoured dead. Induction and interment within its walls enshrines a person as a national hero. Josephine Baker is the sixth woman and the first Black woman to be buried there in her own right, placing her in the same echelon as Marie Curie, Alexandre Dumas, Voltaire, Rousseau, Toussaint Louverture and Emile Zola. Many hailed this as a breakthrough moment of inclusion, reflecting France’s progressive values.

In some ways Baker is a radical and surprising choice. She was a performer, primarily a dancer, and one who danced in a popular Black American style, often seen as exotic and primitive in contrast to classical French traditions. She was not born in France, nor has she left a body of written work, wrought legislative change, or contributed to scientific understanding.

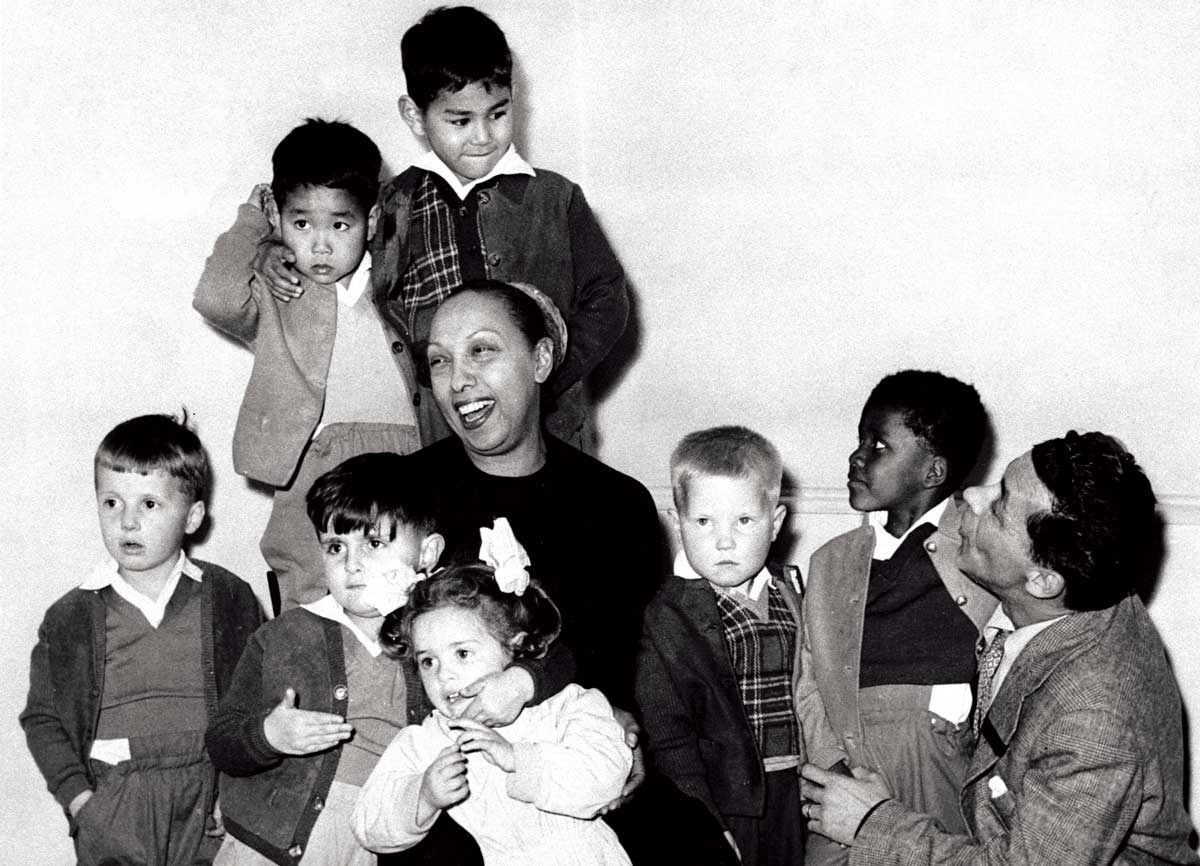

Yet other aspects of her life, and the way it has been celebrated and memorialised in France, show why she was an obvious, even safe, choice. As well as her contribution to French culture, she served as a spy in the Second World War, smuggling messages for the resistance. She attempted to build a multicultural home, embracing and adopting children from across the globe from different faiths, ethnicities and cultures, raising them in a French château. And she chose French citizenship, spoke French, proclaimed her love for the country loudly and often and declared her admiration for the inclusion and welcome she had experienced there. She said, in her speech at the March on Washington in 1963, that she was burned out of her home and beaten with cruel words in America, but that in France she never feared. France, she said, was like a fairyland.

These qualities help explain Baker’s selection and induction. They also help explain the ambivalent reaction to it. France’s national self-image, fostered since the revolution, emphasises equality, liberty, democracy and the French commitment to (and invention of) universal human rights. In his speech honouring Baker at the induction Emmanuel Macron proclaimed that she was a true French hero because she fought for liberty and equality for all.

Another strong aspect of her appeal to the French public is that Baker exemplifies a strand of commentary that contrasts French colour-blindness with American racism. There is more freedom in one square block of Paris, the novelist Richard Wright wrote, than in the whole of America. J.A. Rogers, a Paris-based correspondent for numerous Black newspapers, said: ‘In one respect France is greater than any other country on earth. There is no colour line … All hail the power of France’s name.’ And Gratien Candace, a Guadeloupean politician of Afro-diasporic decent, warned the French not to adopt the American ‘virus’ of racism along with the scintillating sounds of jazz.

French acceptance was facilitated by the fact that American entertainers were safely non-French and welcoming them would not jeopardise the colonial status quo. But, despite the absence of overt segregation, many of them were also regarded as exotic outsiders. Even as Baker was being embraced, she noted in her biography that she wore couture to ward off the curious gaze of partygoers and that at times she felt like an exotic animal on display in the zoo. As she performed what the historian Tyler Stovall has described as ‘colonialist fantasy skits’ at the Casino de Paris in 1931, French colonial subjects performing in the Colonial exhibition, who did not have citizenship, were housed in enclosures at the Parc de Vincennes and unable to leave the grounds without a permit and permission, under escort and with a curfew. That same year the American anti-racist activist, sports hero and Shakespearean actor Paul Robeson told the newly formed League of Coloured Peoples in London that ‘there was something exotic in the French attitude. They seemed to think that fundamentally [I] was a savage’. He may have said this to appeal to his London audience, but the Caribbean jazz performer Ernest Léardée noted in his memoirs that he was once asked to strip naked at a society party and that he ‘had the feeling of walking in a cotton field’. France’s supposed colour-blindness conveniently masked the experience of racialisation.

Even as Josephine Baker praised French race relations, others pointed out that the passion for American black culture and jazz masked the brutal realities of French colonialism and racism. The poets Leon Gontran-Damas and Leopold Senghor, first president of Senegal, were among a growing network of Black French intellectuals and activists in Paris during Baker’s heyday. They showed how universalism often meant assimilation and that equality was undermined by the different legal statuses of various colonies and the socio-economic inequalities linked to racial status. Damas’ poem ‘Hiccups’ recalls his mother urging him to play the violin (a French classical instrument) rather than the banjo (Caribbean, folk, plantation music) and to speak ‘the French the French speak’. The police files at the Paris Police archives in the fifth arrondissement hold endless files of surveillance on colonial subjects, but in the much sparser monitoring and arrest records of Black Americans the officer commonly notes there is ‘little of concern’.

Baker is a seemingly progressive but quite conservative choice of ‘first’ Black woman in the Pantheon. In and after her lifetime she was accepted precisely because she played an exotic stereotype, fulfilling French colonial fantasies, because she was safely American and because she loudly declared that the French were not racist. Her induction is a cause for celebration, but we should not use it to proclaim uncritically French progressive values in action.

Rachel Gillett is Assistant Professor in Cultural History at Utrecht University.

Source: History Today Feed