Leaving Hong Kong | History Today - 8 minutes read

Hong Kong’s summer has been marked by widespread political unrest. The trigger was a proposed bill that would allow the territory’s government to extradite Hong Kong residents to countries with which Hong Kong did not have an extradition treaty. Prominently, these included mainland China. The Hong Kong government argued that the bill would close a ‘loophole’ that made the territory a potential haven for criminal fugitives. To Hongkongers, the bill looked like the latest example of a creeping ‘mainlandisation’.

When the United Kingdom negotiated the terms of Hong Kong’s ‘handover’ to the People’s Republic of China in 1997, the people of the city did not have representation in the discussions. Under the terms of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, Hong Kong would enjoy the status of a Special Administrative Region until 2047, with ‘considerable autonomy’ and would be governed by the people of Hong Kong. Under the terms of the 1986 Basic Law, the territory would preserve its capitalist system as well as independent courts, currency and immigration system.

Swallowed

Yet well before the extradition bill was proposed in 2019, many Hong Kong people expressed dissatisfaction with the growth of mainland influence over the city. A proposed National Security bill in 2003 and proposed ‘patriotic’ school curriculum in 2012 provoked large-scale protests; both were shelved. The attempted introduction in 2014 of universal suffrage for electing the Chief Executive – but only among candidates pre-approved by Beijing – led to the three-month-long ‘Umbrella Movement’, in which major streets around the Central business district and elsewhere were occupied.

Aside from these mass protests, Hongkongers frequently complained about the influx of Chinese tourists and the entire reconfiguration of neighbourhoods to serve them, ‘parallel trading’ in which visitors bought locally available products in bulk in order to re-sell them on the mainland and the increasing proliferation of Mandarin in this predominantly Cantonese-speaking city. At the same time, mainland immigrants were widely seen as competitors for jobs, public resources and private housing, which was among the most expensive in the world. In the face of these changes, the government appeared unwilling or unable to protect the local population. The proposed extradition bill, then, did not merely represent fears that Hong Kong’s residents might be tried in mainland courts, but broader perceptions that Hong Kong was being swallowed and becoming ‘just another Chinese city’.

The case of Peter Godber

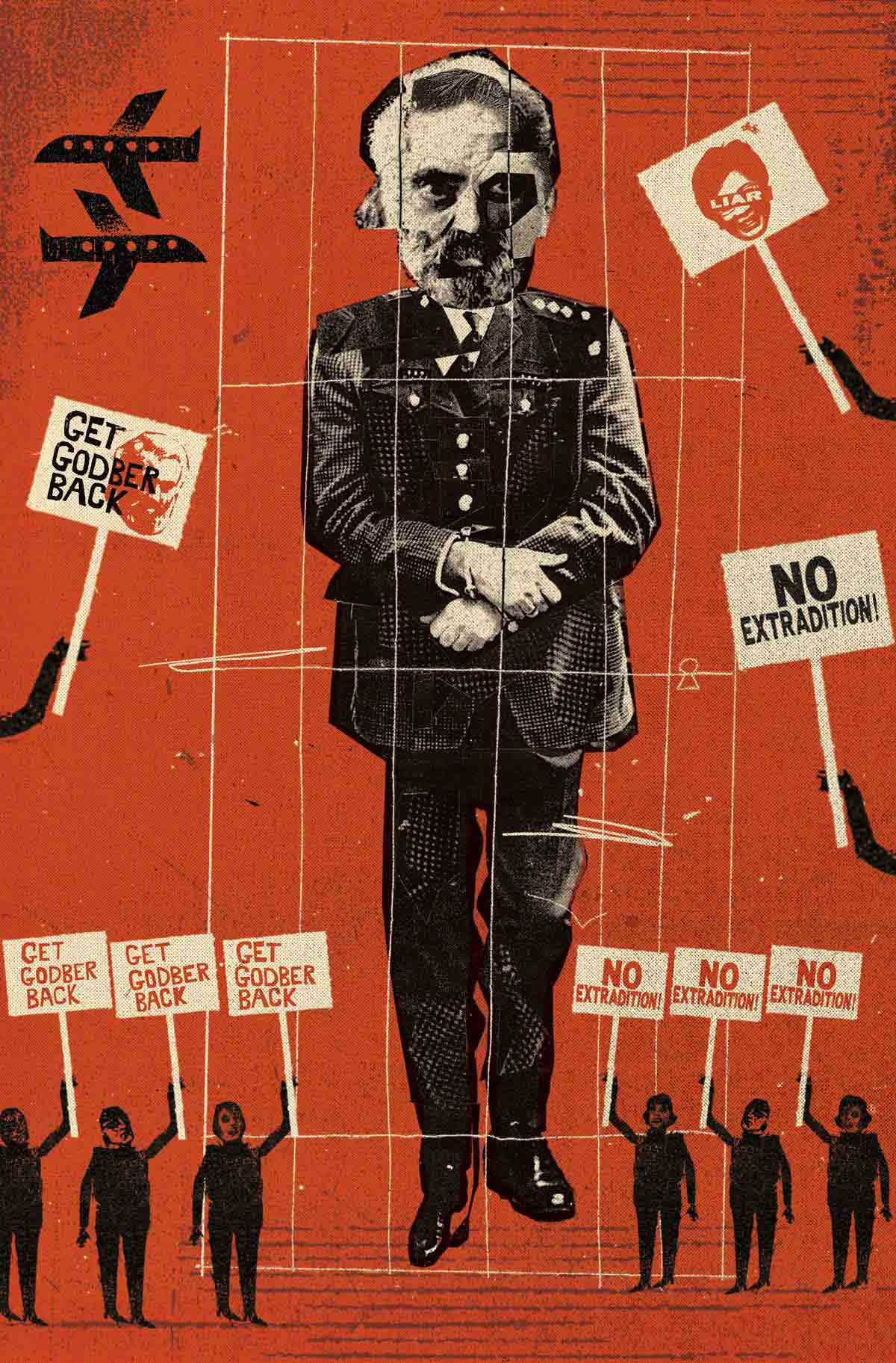

This is not the first time extradition laws have led to large-scale protests in Hong Kong. Nearly 50 years earlier, from mid-1973 to early 1975, while still a British Crown Colony with considerable administrative autonomy under its London-appointed governor, Hong Kong was gripped by a different extradition crisis. As is the case now, many of the protesters were students. The 2019 protests stemmed from distrust of the Chinese legal system and fears that Hongkongers extradited from the territory could be charged with crimes that were not illegal in Hong Kong itself. By contrast, the 1970s protests entailed demands that a foreigner be extradited to Hong Kong. Moreover, in this case, the Hong Kong law was the less liberal one, affording fewer protections.

The foreigner in question was Peter Godber, the British Chief Superintendent of the Hong Kong Police Force. He had grown wealthy by collecting bribes through a franchising system in which lower-level police officers paid in order to have the right in certain districts to collect bribes from ordinary people. For most Hong Kong people, the face of corruption – i.e. the officer to whom they paid ‘tea money’ – was a fellow Cantonese-speaking Chinese. Yet through the franchising system, the greatest riches flowed upward to foreign senior officers such as Godber. In June 1973, realising he was about to be arrested, Godber used his police privileges to bypass passport control, made his way to Singapore and from there to London. Back in the United Kingdom he was free from prosecution, thanks to the principle of double criminality: the Hong Kong law that he was accused of breaking was not a law in the United Kingdom. Godber, therefore, was not subject to extradition.

Unexplained wealth

Godber’s case took place against the background of new stringent anti-corruption laws in Hong Kong. Previously, existing anti-corruption laws were lightly enforced. Such exchanges as kickbacks in business deals, or gifts to nurses in order to ensure better medical care, were unexceptional and generally accepted. By the late 1960s, however, the petty bribes demanded by police officers of small business owners – above all, of hawkers with illegal food stalls who could not afford rents and faced ruinif their stalls were closed – had raised such resentment against the police as to threaten the colonial government’s ability to govern. In the aftermath of a series of major anti-government riots between 1966 and 1968, the governor David Trench decided to take aggressive measures against bureaucratic corruption, including that of the police, culminating in the passing in 1970 of the Prevention of Bribery Ordinance. Clause 10 of this law, as described by the Attorney General Denys Roberts, made ‘it an offence for a public servant to maintain a standard of living not commensurate with, or possess property disproportionate to, his official emoluments’. At the time of the law’s proposal, legal experts at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in London flagged this clause as problematic, but ultimately allowed it to be included. It was this crime, possessing unexplained wealth, rather than bribery per se, with which Godber was charged. Having been given a week to explain his wealth, he fled Hong Kong.

One of their own

Alongside popular resentment against police bribery sat widespread admiration for the police handling of the 1966-1968 riots. In appreciation for the police force’s efforts, the colonial government had arranged for it to be retitled the Royal Hong Kong Police Force. As Deputy District Commander in Kowloon, Godber had played a prominent role in the protest’s containment; to many Hong Kong people he was a hero. Yet his escape from Hong Kong provoked widespread outrage. Several ‘Get Godber Back’ protests and rallies took place in August 1973.

For the authorities in London, extraditing Godber for unexplained wealth was a non-starter. Not only did the concept of double criminality preclude extradition for actions that were not illegal in Britain, but the specific law was anathema to British legal traditions since it violated the presumption of innocence and the right not to incriminate oneself. From a British legal perspective, the protesters’ demands for Godber’s extradition were nothing less than a demand to hand over a British citizen to be tried according to draconian laws that did not respect individual rights. At the same time, recognising the political situation in Hong Kong, the London authorities worked with Governor Murray MacLehose (Trench’s successor) to find a legal means to return Godber to the colony.

To those in Hong Kong, British protestations about double criminality were mere loopholes allowing British old boys to take care of one of their own. The Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS) established 13 anti-corruption groups, with some workers’ unions joining the cause. A petition-signing campaign culminated in a debate at the University of Hong Kong on 12 August and on 26 August a march and mass rally took place in Morse Park and Victoria Park. Further demonstrations took place on 2 and 16 September. According to an HKFS pamphlet, the government’s statement that there was an ‘absence of law’ was a pretext for allowing Godber to evade justice. Particularly jarring to protesters was the discrepancy between the British government’s ability to appoint members to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, or commute death sentences for convicted criminals, but feigned inability to arrest Godber for breaking Hong Kong law. An October editorial in the generally pro-government Sing Tao Jih Pao expressed disbelief that the British government had to find a justification to ‘extradite’ Godber; it argued, in an interesting parallel to the 2019 crisis, that Hong Kong was British territory and therefore the British government should be able to enforce Hong Kong laws within Britain itself.

Resolution

In April 1974 Godber was arrested at his home in Rye and extradited in January 1975, not for unexplained wealth but for bribery itself, based on evidence that was possibly fraudulent, offered by ‘Taffy’ Hunt, a subordinate police official facing charges of his own. Godber was convicted and served four years in prison. In addition, his earlier ability to escape from Hong Kong while under threat of arrest exposed the problems of allowing the Police Force to police itself, leading to the establishment in 1974 (while the Godber extradition was still pending) of an Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC). Godber’s extradition, albeit by questionable legal means, and his conviction, along with the creation of the ICAC, helped establish the Hong Kong government’s reputation for probity and effective representative (not to say democratic) government. It was one of the key events in legitimising British colonial rule in the eyes of many Hongkongers during its final decades. As of early September 2019, it is unclear how its successor will resolve its own extradition crisis.

Mark Hampton is Associate Professor of History at Lingnan University, Hong Kong.