The Adventures of Number 45 - 3 minutes read

On 6 October 1982, a 500-year-old Gutenberg Bible spends a night in the evidence locker of the University of California. There are 48 (possibly 49) known surviving copies of this rare book, printed c.1456 in Germany by moveable type pioneer Johann Gutenberg. Representing one of the earliest major works of European printing, it is estimated that only around 180 of these Latin Bibles were ever produced.

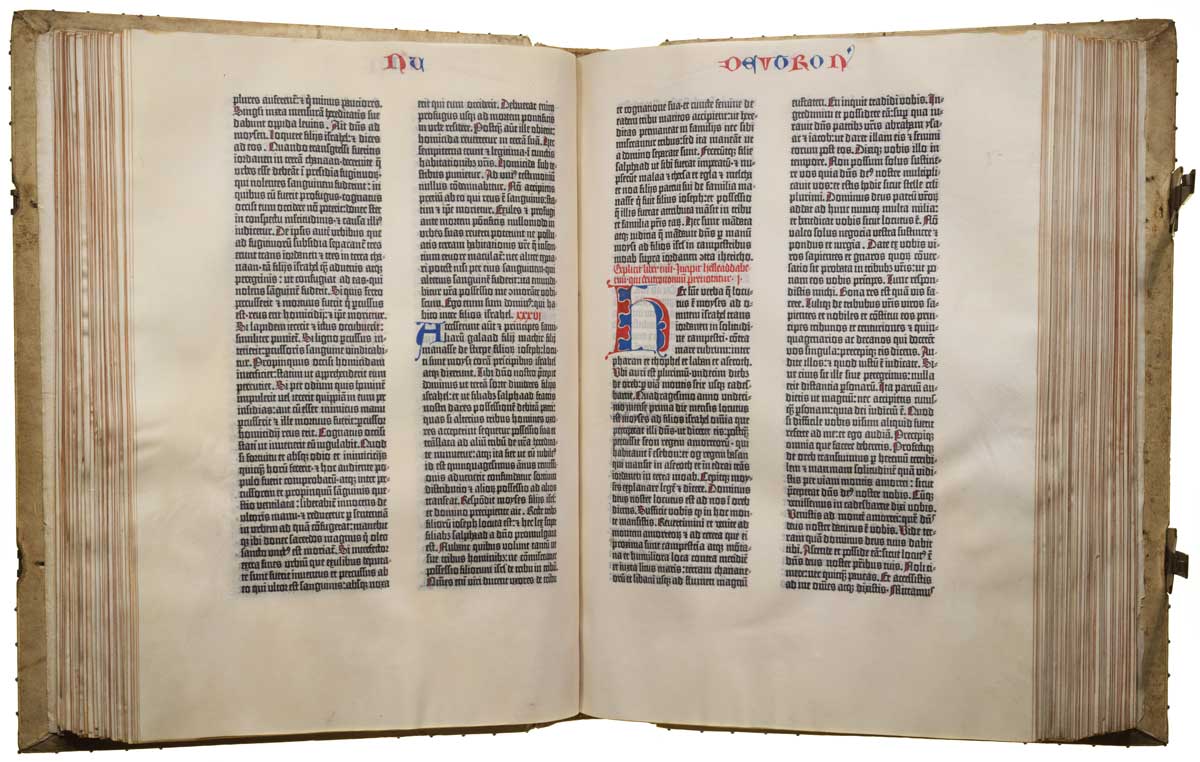

This particular leather-bound tome, which found itself nestled among seized handguns and marijuana in 1980s California, is known in elite collecting circles as ‘Number 45’. Among the surviving copies, Number 45 is considered an especially fine example. It is printed on calfskin (vellum) and, rarer still, retains the original binding. The famous Gutenberg ink remains glossy, the large pages are unblemished and the hand-finished illumination contains brightly coloured penwork.

The book has survived in almost perfect condition for over 500 years but on this night its custodians are nervous. The book’s sleepover in the police lockup has been meticulously planned months in advance – it happens to be the only room on campus which doesn’t have an automatic sprinkler system. The next morning the book is to be taken to the Crocker Nuclear Laboratory where it will undergo cutting-edge particle analysis and help kickstart a new approach to book history research.

This is one of the many exciting adventures of Number 45 that Margaret Leslie Davis recounts in The Lost Gutenberg. The narrative tracks Number 45 as it travels from Gutenberg’s workshop in Mainz, thrives during the 19th century and finally arrives in its present home in Keio University, Tokyo.

Davis records the history of this book with enthusiasm and attention to detail – qualities that can also be attributed to many of the book’s hunters and custodians over the years. ‘Hunter’ is a particularly apt term here since, as Davis shows, this Gutenberg Bible and its surviving siblings have become some of the most sought-after books produced in the West, inspiring lifelong searches and intense rivalries and commanding eye-watering prices at auction. The last private collector of Number 45, Estelle Doheny, paid $72,000 in 1950; it was last sold to a Japanese firm in 1987 for $5.4 million.

The value of rare books – personal, cultural and financial – are recurring themes. Davis reminds us that books have long been objects of desire but shows that their perceived value is connected to a constantly shifting social and economic context. The tales of frenzied aristocratic bibliomania occur during what she calls the ‘Imperial Century’, when the prices were high and the reputational stakes higher.

Number 45’s late-19th-century owner Lord Amherst, for example, boasted a private museum that included Egyptian funerary objects and Mesopotamian clay tablets, which drew a steady stream of gentlemen scholars. His rare book collecting was part of his pursuit of a ‘cultivated, well-ordered empire’. The links between book collecting and colonial expansion are implied, but not interrogated. But there is a sense of irony as many rare books, including Number 45, begin to scatter from the libraries of the English gentry and the ‘Imperial’ makes way for the ‘American’ and the ‘Asian’ centuries.

The book now exists as a series of digital images hosted by Keio University Library, online and publicly available. The pages are still bright and the ink remains crisp, almost as though it had just rolled off the press.

The Lost Gutenberg: The Astounding Story of One Book’s Five-Hundred Year Odyssey

Margaret Leslie Davis

Atlantic

304pp £16.99

Diane Scott researches late medieval and early modern book history at the University of Glasgow.