The State of Myanmar | History Today - 7 minutes read

In late 2019 Myanmar was summoned to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague. A delegation led by Nobel peace prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi attended the hearing in order to defend the state against charges of genocide against the country’s Rohingya minority. The ICJ has no powers of arrest, but in January the court ruled that Myanmar must take steps to protect the Rohingya.

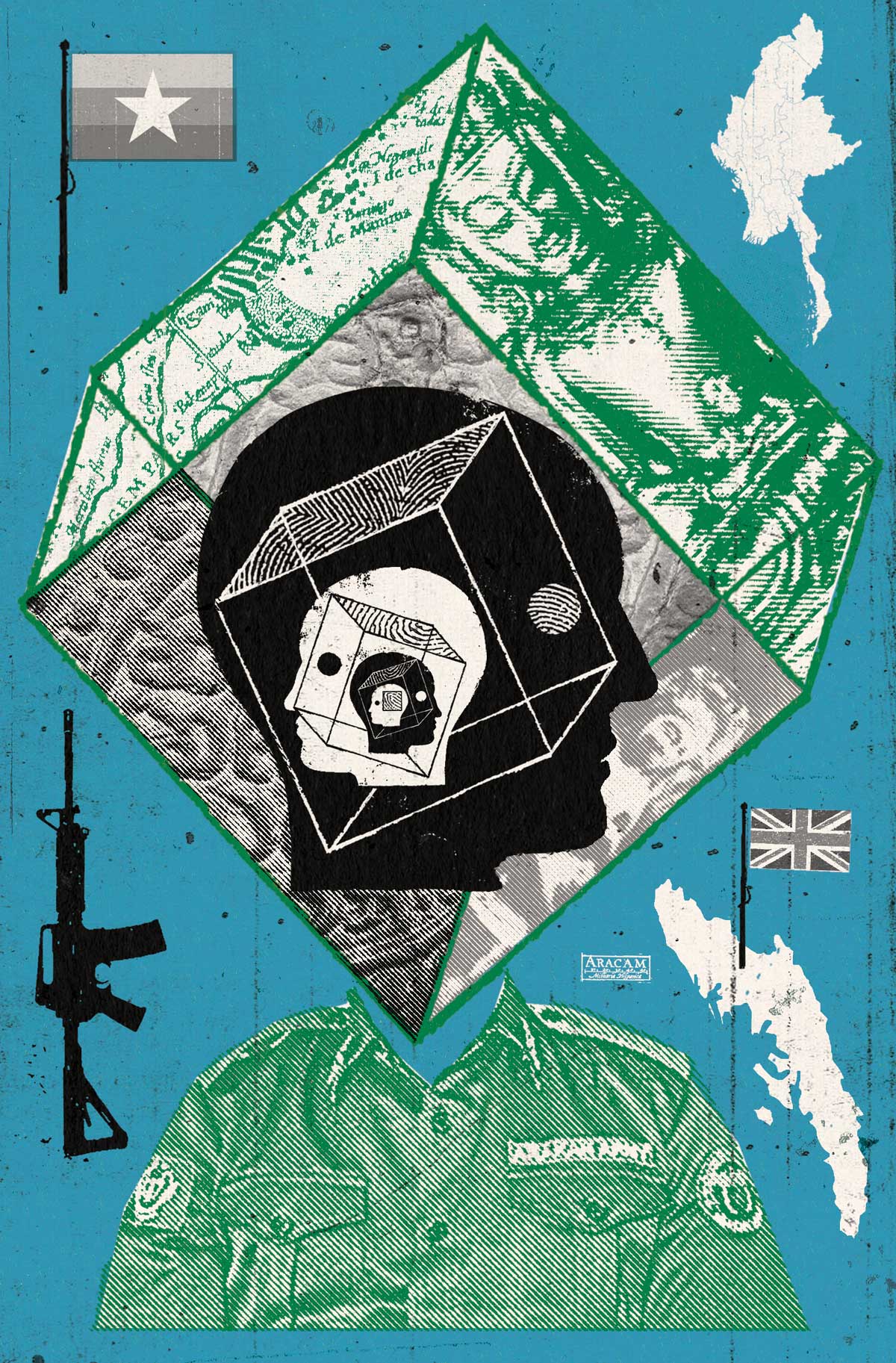

The charges came about following the ongoing situation in Rakhine State on the country’s western coast. In August 2017, amid an increasingly state-led crackdown, a militant group called the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) launched an attack on a security post in Rakhine. In response, the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) launched what they called ‘clearance operations’, but what others called ethnic cleansing. By September, Médecins Sans Frontières estimated that as many as 9,000 Rohingya had died the previous month.

Currently, around one million Rohingya refugees have fled to neighbouring Bangladesh. A third player in the region is the Arakan Army, an ethnic militia comprised mostly of Buddhist Arakanese people, who are antagonistic to both the ARSA and the Tatmadaw. In recent years they have begun deadly raids on Tatmadaw outposts. There have also been widespread incidents of violence between the Muslim Rohingya and Buddhist Arakanese.

Kingdoms come

To understand why Rakhine State is in such turmoil we need to follow the threads of ethnic nationalism back to before Myanmar existed and the region was occupied by warring kingdoms. One of these kingdoms was Arakan, a sovereign entity on the eastern coast of the Bay of Bengal, which claimed a heritage going back to the time of the Buddha. By the 16th century it had become an important regional hub with Arab, Portuguese and Dutch sailors arriving on the coast to trade, among other things, slaves. Portuguese pirates even ended up becoming mercenaries for the Arakan kings Min Bin (1531- 54) and Min Yazagyi (1593- 1612) and assisted in fending off invading Burmese armies from the interior. Based around the town of Mrauk-U, Arakan was a nominally Buddhist kingdom, though it was tolerant of Muslims and there was even syncretism at the highest level, with kings adopting Islamic titles and employing Muslims in their administrations.

Arakan was conquered by the Burmese king Bodawpaya in 1784, as the Burmese empire grew. As well as dismantling the kingdom, Bodawpaya captured the much-coveted ‘Mahamuni’ image, a six-ton figure of Buddha that legend says was sculpted from a first-hand encounter. To this day, the Mahamuni image sits in a pagoda near Mandalay, far from Arakan. For modern Arakans, the memory of the deposed kingdom is a point of grievance. It is invoked by the Arakan Army to help their local recruitment.

Some 100 years after the fall of Arakan, it was the Burmese Empire that fell. The First and Second Anglo-Burmese Wars in 1824 and 1852 had already annexed lower Burma and Arakan, but the decisive blow to Burmese sovereignty came in 1885. The British sailed up the Irrawaddy River on steamships to the royal capital of Mandalay and sacked the palace. King Thibaw was sent to India in permanent exile and virtually the entire system of Burmese governance was dismantled, from the nobility to hereditary township posts.

The colonial state was also a surveillance state and British censuses demanded detailed information of individuals. In this way, western thinking about race was imported into Burma. Ethnic self-identification in South-East Asia was never as rigidly defined as the categories that the colonial authorities attempted to put people into. For instance, some people might identify as Shan in one context and Kachin in another. In developing taxonomies of people, it was also easy to overwrite major differences in the languages or religions of those supposedly belonging to the same group.

Burma was the eastern frontier of British India and many Indians were encouraged to settle in urban centres, such as Rangoon (now Yangon), where they were above the local Burmese in the colonial hierarchy. British civil servant J.S. Furnivall called cosmopolitan Rangoon the ‘plural society’; this was not multiculturalism in today’s meaning of the term, though, but a rigidly organised division of labour along racial lines, a microcosm of colonial capitalism.

‘Taingyintha’

When independence came in 1947, the Burmese inherited a military state and the legacy of authoritarianism has persisted. In 2018, two journalists, who had reported on the extra-juridical execution of ten Rohingya men by the Tatmadaw and Arakan villagers, were sentenced to prison under the Official Secrets Act, a law dating from the British era.

By the 1960s, as democracy collapsed into dictatorship, the concept of the taingyintha, or ‘national races’, became central to political discourse. The idea of taingyintha was a blatant attempt at nation-building, pushing the idea that the country’s many ethnic groups were a unitary whole. The word appeared in books, speeches and the 1974 constitution, yet its efficacy has been debatable. Since the end of the Second World War, the country had been carved up into multiple arenas of civil war, mainly along ethnic lines. That these wars persist highlights that the unity in diversity rhetoric failed to win hearts and minds. Despite the multicultural rhetoric, Burma was a state virtually monopolised by the majority Bamar ethnic group, whose language, Burmese, was, and is, the official language. Both military leaders such as General Ne Win and pro-democracy leaders such as Aung San Suu Kyi called for integration, but spoke from a position within the dominant culture and were thus unable to recognise what other ethnicities were calling for, such as the right to teach in their own languages.

Late arrivals

For the Rohingya, the political use of ethnicity was deadly. The Burmese state was at war with many ethnic groups, but at the same time accepted them as part of the taingyintha. The Rohingya, however, were seen as late arrivals. In 1978, Operation Nagamin (Dragon King) drove hundreds of thousands of Rohingya across the border from Arakan into Bangladesh. Most were eventually allowed to return, but their situation did not improve. The 1982 Citizenship Act made membership of the taingyintha virtually the only way to claim full citizenship and 1823, the year before the British took lower Burma and Arakan, was the cut-off point. Debate has raged ever since about whether the Rohingya were in Arakan prior to this point or were later immigrants under British rule. Many in the seats of power had already decided that the Rohingya were not taingyintha and began to punish them through military operations and complex registration processes. The violence in 2017 was the result of decades of delegitimisation. The state began to deny that the Rohingya even existed, claiming they were ‘Bengalis’. Aung San Suu Kyi, in a widely reported address to the international community, refused to even use the term.

Religion is central to the current strife. The Buddhist sangha was one of the few Burmese cultural institutions that managed to survive colonialism and thus became an incredibly important part of Burmese identity during the nation-building phase, to the detriment of the country’s other religions. Buddhism has been the hinge between the Arakan and Burmese in their united antagonism towards the Rohingya. While the authorities have claimed that army operations are not anti-Islamic, the current violence has occurred amid a wave of ethno-nationalist preaching by high profile monks. Since 2012, violence against non-Rohingya Muslims has flared up, not just in Arakan, but in interior cities such as Mandalay, Meiktila and Bago.

It is impossible to say how things might have been different if British rule had not stretched this far east. Perhaps Myanmar would not exist at all, for the Bamar inherited a state whose borders had been drawn by the British. Humiliated under colonial racism and authoritarianism, the Bamar majority built a nationalism that was based on the Burmese language and Buddhism combined with an authoritarian state apparatus inherited from the British. The results have been tragic.

Ewan Cameron has worked in Myanmar education since 2009 and regularly contributes to Myanmar journals and media.

Source: History Today Feed