Liverpool’s Slave Trade Legacy | History Today - 6 minutes read

In 1787 the Quakers of Portsmouth made their anti-slavery campaign official by forming The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, joining forces with prominent abolitionists such as William Wilberforce. So organised were they in their methods of activism, such as civil disobedience, research and evidence-gathering, that they set the blueprint for many future lobbying organisations.

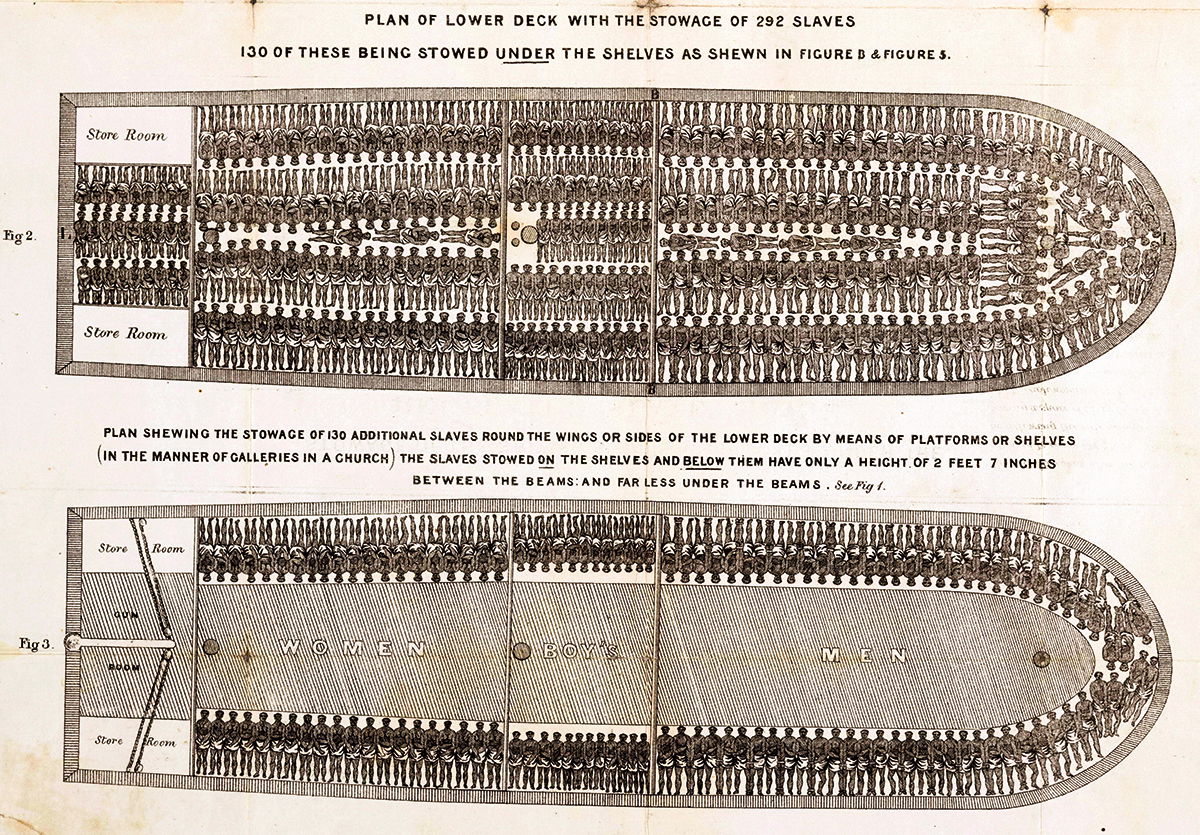

One of their most effective actions was to commission an illustration of the Liverpool slave ship the Brookes, named after its owner, Joseph Brookes, and present it to the nation in poster form, appearing in newspapers, pamphlets, books and coffee houses. The horror it showed quickly established the illustration as a hugely influential part of the abolitionists’ anti-slavery campaign.

The architect of the use of the Brookes as political propaganda was the Quaker abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. In The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament (1808), he wrote that the ‘print seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it, and was therefore instrumental, in consequence of the wide circulation given it, in serving the cause of the injured Africans’.

Clarkson’s choice of the Brookes proved to be a revelation to large numbers of people. As he travelled around England, galvanising the anti-slavery campaign, he was attacked in Liverpool in 1787 and nearly killed by a gang of sailors paid to assassinate him.

Over 25 years, Brookes’ ship made ten Atlantic crossings, carrying in total 5,163 captured Africans. Of those, 4,559 survived, meaning that over ten per cent of its prisoners died. Records from The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database show that on its 1785-86 voyage it carried 740 enslaved Africans, 258 more than the 1788 poster showed. In 1788 The Regulated Slave Trade Act had been passed, the first British legislation to regulate slave shipping. It limited the number of slaves an individual ship could transport.

Although Liverpool was late entering the slave trade, by 1740 it had surpassed Bristol and London as the slave-trading capital of Britain. In 1792 London had 22 transatlantic sailing vessels, Bristol had 42 and Liverpool had 131. The Brookes was built at the height of Liverpool’s slave-trading empire and, by that time, the city’s shipbuilders had mastered the art of constructing custom-built slave ships: in the early 18th century the average size of a slave ship was 70 tons; by the end of the century this had tripled to 200 tons.

Such was Liverpool’s dominance of the North Atlantic slave trade that one in five African captives crossing the ocean was carried in a Liverpool slave ship. The city had the capacity to build bespoke ships to the exact specifications and requirements of the slave merchants. Consequently, the industry employed 3,000 shipwrights, alongside other ancillary trades, such as rope makers, gun makers and those who supplied comestibles to be carried on board.

Liverpool’s economy and the economies of neighbouring Lancashire and Yorkshire benefited, too. Ships bound for Africa would be laden with goods to appeal to African traders to make the outbound journey profitable. Textiles from Lancashire and Yorkshire mills were the most attractive commodity and made up perhaps 50 per cent of the outbound cargo, alongside guns and knives, brass cooking pots, copperware, clay pipes, beer and liquor. Local craftspeople and small industries supplied the ships and estimates suggest that one in eight of Liverpool’s population – 10,000 people – depended on trade with Africa and 40 per cent of its income derived from the trade.

The slave trade was the backbone of the city’s prosperity and the reinvestment of proceeds gave stimulus to trading and industrial development throughout the north-west of England and the Midlands. Liverpool’s Rodney Street was built between 1782 and 1801, providing town houses for many elite merchants, including John Gladstone, father of prime minister William Ewart Gladstone.

It was named after Admiral Rodney, who defeated the French in St Lucia in 1782 to preserve the British influence in the West Indies. Rodney supported the slave trade. Elsewhere in the city, the Port of Liverpool Building displays stone carvings of slave ships and dolphins on its façade and the Cunard building carries sculptures of a native American and an African man and woman.

The Liverpool street immortalised by the Beatles in their song ‘Penny Lane’ takes its name from the slave trader James Penny, who was vocal in his opposition to the abolition movement. Eager to protect his business, he boldly claimed in evidence to the Lords Committee of Council set up in 1788 that: ‘The slaves here will sleep better than the gentlemen do on shore.’ He was not the only Liverpool figure to campaign – in the build-up to the 1788 Act, Liverpool slave traders submitted 64 petitions to Parliament arguing against abolition.

In 1999 Councillor Myrna Juarez proposed that Liverpool City Council debate a motion to ‘express remorse for the effects of the slave trade on millions of people worldwide’. This unleashed a controversy, as some protested the incongruity of this debate taking place in a town hall where images of African slaves were moulded into the plasterwork. Nevertheless, the council acknowledged Liverpool’s involvement in the slave trade and a formal apology was made. Today the city acknowledges its slaving maritime history with the International Slavery Museum, which opened in 2007 as part of the Maritime Museum.

Meanwhile, support is growing for a new British slavery museum in the capital after the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, backed the proposal, arguing that it would help to tackle racism. Other institutions have also acknowledged the role of slavery in their history, such as Harewood House in Yorkshire. In September 2018 Glasgow University, in a welcome move, published a report into its historical links to slavery, acknowledging that, although the university did not invest directly in the slave trade, it did receive donations from those who did.

In 1807 The Slave Trade Act saw the official end of the slave trade in Britain. As the anniversary of this act on 25 March approaches once more, taking the lead from Liverpool, it is time that more individuals and institutions be transparent about the legacy that slavery has left.

Claire Shaw is a freelance writer and author of Historic Walks in York (Destinworld, 2020).