Petticoat Alley: London’s Forgotten Women’s Clubs - 6 minutes read

The recent controversy at the Garrick Club has shone a fresh light on the question of women being admitted to private members’ clubs. Yet the history of London clubs is not – as is often thought – as simple as men keeping women at bay.

London has long been the global ‘capital’ of social clubs, home to over 600 such establishments from the 18th century to the present (not including thousands of ‘spin-off’ institutions, from sports clubs to working men’s clubs). Other cities have had social clubs, but none has had the concentration of London, which had 400 clubs by their Edwardian heyday. But while the prevailing image of them is of quintessentially masculine spaces, with ladies only admitted as guests on sufferance, this is not the case.

The first club with female members was launched in 1770 at 48 Pall Mall, making it older than all but three of today’s clubs. Ladies’ Boodle’s – otherwise known as ‘The Female Coterie’ – was a bold experiment in which female members could only be proposed by men, and men could only be proposed by women. It proved a short-lived experiment, closing by 1779.

‘Clubland’ – the concentration of clubs in London’s West End – assumed a masculine membership in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. But clubs did not exist in isolation: their main rivals in these early years, and existing side-by-side with them, were the salons, such as Almack’s (later Willis’s), which had ticketed admission rather than a membership; the early clubs emulated them. These salons were not only mixed-sex, but run by ‘Lady Patronesses’, who strictly controlled admission. Thus even in its earliest years, Clubland was never an entirely male space.

It is no coincidence that the passing of the last of the salons coincided with the first of the ladies’ clubs opening, in the 1860s. The ladies’ clubs are an often-overlooked but substantial part of Clubland, numbering at least 86 establishments, mostly concentrated to the north of Piccadilly, in an inverted U-shape, around Dover Street, Grafton Street and Albemarle Street, a district which became known as ‘Petticoat Alley’.

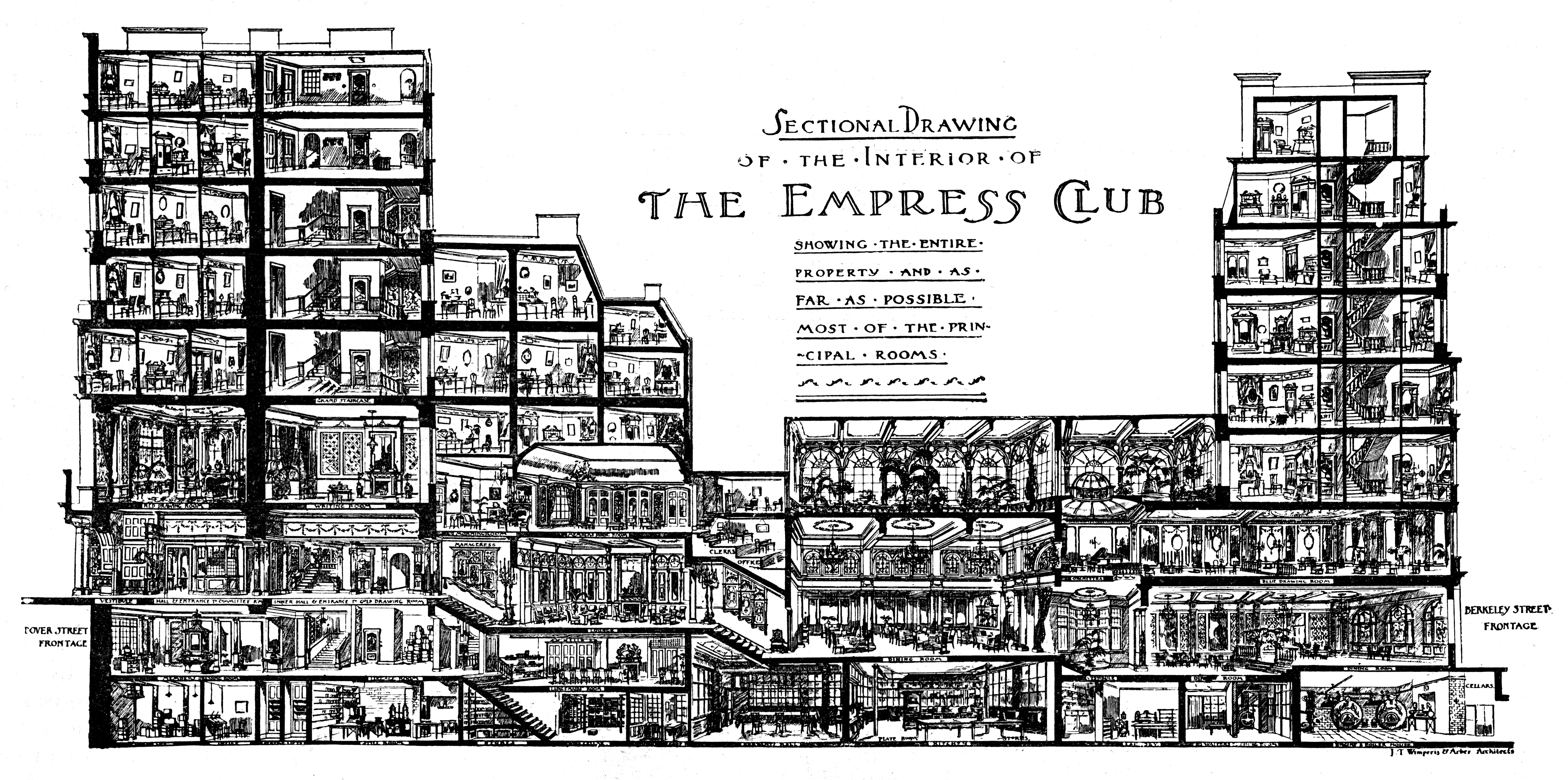

There were two main types of women’s clubs. The first, described by historian Erika Rappaport, was the shopping-based club, like the Empress Club or the Pioneer Club. These made the most of their proximity to Oxford Street and Regent Street to serve as a reputable and safe base for middle-class ladies to entertain on their shopping trips into town – one of the few occasions when Victorian women had financial independence. These could be boldly ambitious: in the 1900s, Constance Smedley founded the Lyceum Club as the base for a whole global network of Lyceum Clubs. Although the London progenitor did not survive the 1930s, many of her overseas Lyceum Clubs continue today, from Australia to France.

The second type of club also had a strong emphasis on respectability. These were the residential clubs, with numerous permanent (or semi-permanent) residents. They could be upper-middle class, such as the Columbia Club in Kensington, or working-class, such as the Soho Club on Greek Street. In either case, they offered affordable, secure lodgings to professional women. By the time London’s clubs peaked in 189s0-1910, the two types of women’s clubs were a vital component of Clubland, with their own sections reserved in almanacs.

Given the scope of these clubs – and they typically had anything between 300 and 900 members apiece – one might ask where they went. It has been claimed that they closed down because there was no demand for them. There is little evidence to support this. Instead, in the 20th century, they became victims of their own financial model. Most clubs – including the men’s clubs – have suffered a high rate of attrition, with 90 per cent having gone bankrupt over the years. The women’s clubs were more financially vulnerable than their male counterparts, because of how they were funded. Men’s clubs typically asked founder-members to dig deep in furnishing a new club with capital and permanent premises. Victorian women, by contrast, were far less likely to control their household budgets and so it was much rarer to find a critical mass of women able to club together to raise significant capital sums. The result was that ladies’ clubs typically turned to philanthropy to make up the shortfall. Consequently, there was a culture of women’s clubs becoming dependent on one (or more) wealthy female patron. Unfortunately, this dependence meant that, 20 or 30 years after the club’s foundation, the death of the patron would usually trigger a financial crisis, often followed by the club’s bankruptcy. Women’s clubs began closing in the Edwardian era, with the closures mounting in the interwar years. By the early 1970s, there was only a solitary survivor, the University Women’s Club in Mayfair (which still exists today).

There was also a brief Victorian vogue for mixed-sex clubs, with around 50 cropping up in the late 19th century, also centred around Petticoat Alley. Unfortunately, the trailblazer for these, the Albemarle Club on Albemarle Street, also contributed to their unpopularity. As the setting for the Wilde scandal – the Marquess of Queensberry left his infamous note for Wilde there, ‘To Oscar Wilde, posing as a somdomite [sic]’ – their reputation for moral rectitude suffered a hit and they became the butt of jibes about the kinds of men who would mix with women in a club. They died a slow death, so that by the mid-20th century they were all but extinct. For the first time in its existence Clubland in the 1950s was a largely female-free zone; lodged in the public memory thereafter as ‘the way things have always been’.

Yet there was always an appetite for clubs for women and, once the ladies’ clubs closed down, this briefly found expression in another form: the Ladies’ Annexes. Members of the men-only clubs established these as a compromise, not wanting to admit women to their clubhouses. Unfortunately, the annexes were hopelessly uneconomical, effectively doubling a club’s overheads with a second building, and so most had closed by the 1960s. Today, only the annexe of the Oxford and Cambridge Club survives, fully embedded into the building.

Women’s admission into the traditional gentlemen’s clubs happened sporadically, and was often prompted by financial desperation rather than latent feminism. A smattering of establishments paved the way, from the Chelsea Arts Club and RAF Club in 1966, to the National Liberal Club in 1976. The Reform Club was the first Pall Mall club to follow in 1981. But it was not until the 1990s that the bulk of men’s clubs in London opened up to female members. Today there are some 50 historic London clubs which survive, of which 12 are men-only, and one is women-only. Yet a common fallacy is to see these often fusty-looking establishments and to imagine they are typical of what came before.

Seth Alexander Thévoz is author of Behind Closed Doors: The Secret Life of London Private Members’ Clubs (Robinson, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed