Coda’s new features take on Microsoft Word and Google Docs - 6 minutes read

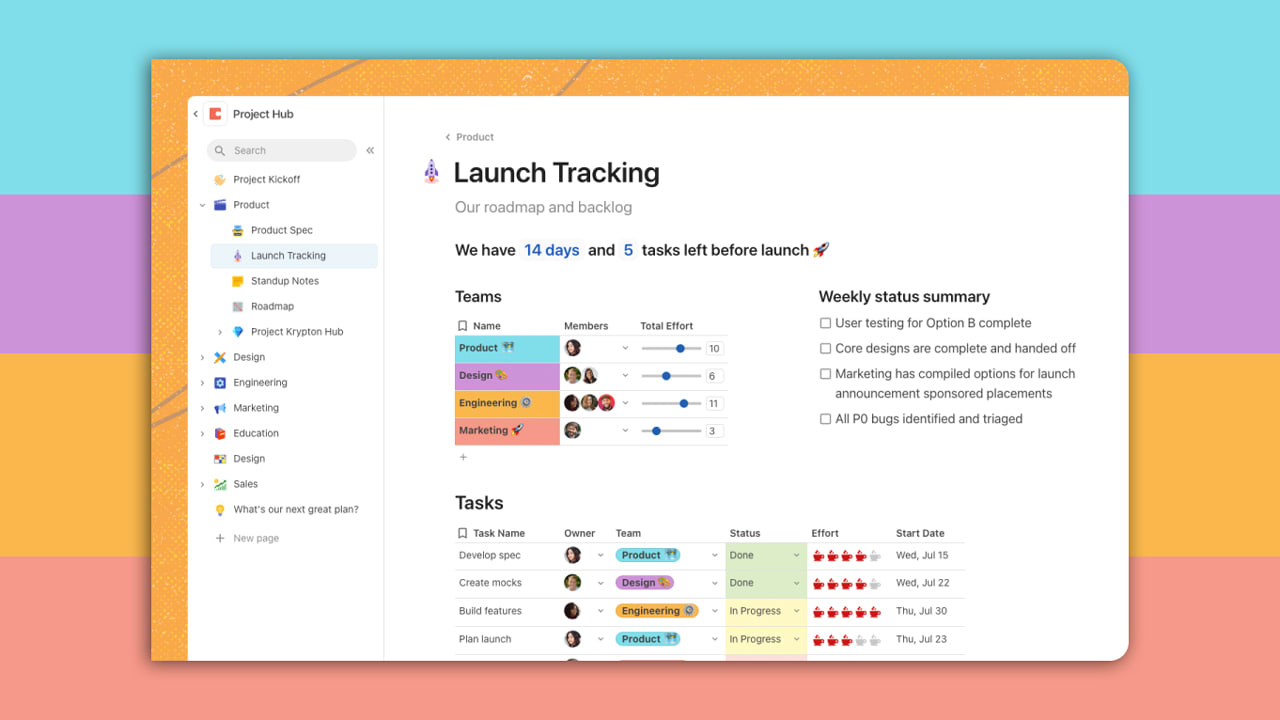

With Coda, users can create free-flowing pages full of tables, planning boards, and other interactive elements, but that complexity has sometimes hindered the core editing experience. The overhaul lets users more easily select text from across an entire document, drag elements around the page or into a dual-column view, and edit the same part of a document that a team member is already working on without conflicts. At the same time, Coda is taking a major step toward its vision of making documents feel more like apps. Users can now create “Packs” that tie into third-party services—for instance, with a page that updates Shopify listings remotely or automates sending Slack messages—and can sell those Packs to other users. Coda will offer a marketplace in which Packs creators keep 70% of the revenue, and creators who bring in new Coda customers will keep 20% of any revenue generated in the customer’s first year. Coda CEO and cofounder Shishir Mehrotra says the update aims to expand what’s possible for power users while also making the editor more hospitable for casual use.

“I always tell the team, our goal is to be the blinking cursor of choice for 2 billion people in the world, so to achieve that, you need to be at that level of familiar and delightful from the start,” he says. In the race to reinvent document editing, Coda hasn’t enjoyed the same level of attention as rival Notion. The latter has 20 million active users, versus Coda’s 1 million-plus, and Notion is valued at $10 billion, versus a $1.4 billion valuation for Coda. That’s partly because Notion launched in 2016, giving it a two-year head start, but Notion has also more aggressively courted individual users, offering a generous free tier with no limits on document size.

By comparison, Coda has focused more on large teams. While its free tier is more restrictive—each document is capped at 50 “objects” (such as pages and tables) and 1,000 rows—it charges teams only for users who create new documents. Those who only edit and view existing documents don’t have to pay. Mehrotra says tens of thousands of teams use Coda today. Still, both companies are moving in the same general direction with their products. Like Coda, Notion has also been quietly ironing out the kinks in its editor, and has leaned into extending the software through Templates, which can transform documents into ready-made tools for project management, habit tracking, and more. Coda, however, seems to be moving a bit faster in making its Packs feel more like full-blown apps. Now that anyone can create a Pack, users are no longer confined to whatever data they put into a document themselves. Instead, they can pull in information from services such as Google Docs or Zoom, and can use Coda to trigger tasks in other services as well.

“What people end up doing with Packs often ends up fundamentally changing the use cases for them,” Mehrotra says. “It sort of changes their expectations of what a doc can do.” As an example, the company referred me to Aaron Veale, cofounder of a user research startup called Blossom. Veale had originally intended to build Blossom as a stand-alone app for analyzing the interviews that companies were conducting with customers over Zoom. He then pivoted to building Blossom around Coda when he realized that one of his customers, Figma, was already using the software extensively. Blossom’s Coda Pack allows companies to automatically pull in videos and metadata from Zoom, combine it with data from other platforms, and create charts that other team members can edit or comment on. “I realized I could build 80% of my product over the weekend in Coda and, more importantly, I could build almost 100% of competitors’ products probably in a month. So that was the ‘aha’ moment,” he says.

To encourage that kind of adoption, Coda has set aside $1 million in grant money for Pack creators. Blossom was among the first recipients. Mehrotra, who was YouTube’s VP of product before founding Coda, says he hopes the grants and revenue sharing will foster an ecosystem of creators, similar to what he helped establish at YouTube. “It’s pretty informed from what I learned there: If you can create a model for creators to be able to use your platform and take it to new places, they’ll bring the platform with it,” he says. The concept of Packs largely caters to what Mehrotra refers to as the “high ceiling” of Coda use cases—those that stretch the boundaries of what a document can be. But he also realized Coda wasn’t catering enough to the “low floor” of users who just wanted a writing tool to replace the likes of Microsoft Word and Google Docs.

Certain things that are table stakes in traditional document editors, such as selecting text across multiple paragraphs, just didn’t work. And if users tried to edit a block of text that someone else was actively working on, they could lose their progress. Coda’s block-based editor, in which any line can be dragged around or transformed into something different—like a table or a subpage—was getting in the way of basic editing. So a couple of years ago, Mehrotra set aside a half dozen engineers to bring the editor up to parity with apps like Word and Docs, which he refers to as “flow based” editors. While it sounds simple, Mehrotra says combining the feel of those products with the block-based capabilities of Coda was a major undertaking. “It’s hard to overestimate how difficult it is to get an editor that works with both,” he says. “I would argue that there’s not another one that has that feeling of a block-based editor—where I feel like it can design a wiki or web page but also still feel like a flow-based editor.”

Both Microsoft and Google seem to have noticed the threat posed by upstarts such as Coda. Last November, Microsoft announced its own block-based editor, called Loop, though it hasn’t launched the product yet. Google, meanwhile, has been bringing some block-like elements to Docs, including pageless formatting and “Smart Chips” that pull in data from other Google apps such as Maps and Calendar. As before, Mehrotra argues that both companies will have trouble adapting. Microsoft will have to convince customers to use an entirely new app, while Google will have to be careful not to alienate users with major changes to its existing editor. “I think in both cases, it’ll be a really interesting business school case study,” he says. “A market emerges, and two of the largest players take the two opposite approaches to go after that market, and what happens?”

Source: Fast Company

Powered by NewsAPI.org