Studying the effects of interruption on motivation - 3 minutes read

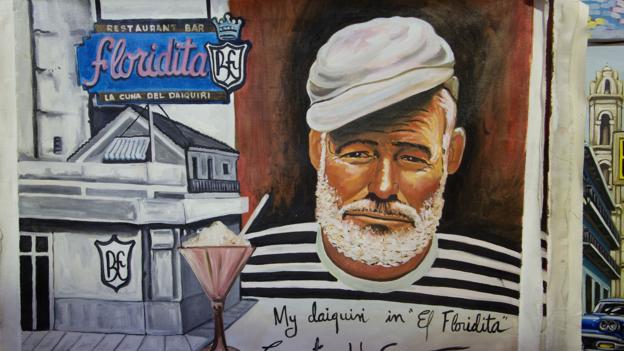

How to conquer work paralysis like Ernest Hemingway

How to conquer work paralysis like Ernest Hemingway“That's the same thing that's in action here, that we tend to want to complete something, especially if it's close to making sense or close to achieving some sort of goal,” says Manalo.

While part one of the study appeared to back up Hemingway’s theory, copying out text is hardly the kind of task that most people do regularly, so the researchers decided to check if the results would also work in more everyday scenarios. They wanted to see if the technique works best if you’ve already planned out what tasks lie ahead of you so that you can gauge how much work is left.

The researchers split a class of 131 students into two groups, and asked them to write about their memories from kindergarten to high school (from when they were four to 18 years of age) – a mammoth task. In group one, they were given help structuring their answers; they were told to split their memories into two parts, kindergarten to elementary school, and junior high school to high school. The others were given no such help. Before they started, the students were asked how motivated they felt.

Again, once most of the students were close to finishing the task, everyone was asked to stop. They were asked how close they were to completing it and how motivated they felt to continue. As previously, the students who were the closest to finishing felt the most motivated. But this time another effect emerged – crucially, those who were asked to divide the task in two, and consequently might have found it easier to gauge how much time they had left, were also more interested in getting back into it.

The findings fit neatly with the research of Daniella Kupor from Boston University who looked into the effects of interruptions in 2014. For one study, Kupor and colleagues from Stanford and Yale universities asked people to watch a short clip in which a comedian relayed a childhood anecdote. Half were allowed to watch the joke to its climax, while the others were left hanging.

Next the participants were asked to do some imaginary online shopping, for a seemingly unrelated study. They were told what to look for, and then presented with two potential purchases, which may or may not fit the bill. When asked, those who had been interrupted in the previous study were significantly more likely to commit to buying something, rather than keep looking.

Source: Bbc.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org

Keywords:

Ernest Hemingway • Object (philosophy) • Action theory (philosophy) • Research • Skill • Employment • Research • Student • Social group • Memory • Kindergarten • Secondary education • Group races • Kindergarten • Elementary school • Middle school • Student • Student • Student • Boston University • Stanford University • Comedian • Online shopping •