Black faces in high places: how Simon Woolley revolutionised British politics - 12 minutes read

In the mid-90s, Simon Woolley believed British politics was largely indifferent to minority communities. In 1995, there had been riots in Brixton, south London, after Wayne Douglas, a 26-year-old Black man, had died in police custody, while, after a spate of street robberies, Paul Condon, commissioner of the Metropolitan police, had written a letter to 40 Black community leaders, saying: “Many of the perpetrators of mugging are very young Black people.” The Macpherson report, which found there was “institutional racism” in the Met, was four years away. There were just seven ethnic minority MPs in parliament.

“Black people were going into police cells fit and healthy, and coming out in body bags,” Woolley remembers. So in July 1996, he launched Operation Black Vote (OBV) outside the House of Commons. “I said: ‘We’ve got to stop rioting and seize power.’”

The name was a subversive nod to controversial police activity such as Operation Swamp 81, in which Brixton was flooded with police, who stopped and searched more than 1,000 people in six days, and led to the 1981 uprising. But if Woolley had a revolution in mind, it was a democratic one – OBV was an attempt to leverage the “Black vote” to ensure politicians took racism seriously, and to increase the representation of Black and minority ethnic people in public institutions (“Black faces in high places”, as Woolley puts it).

In the 1992 general election, John Major had won a majority of 21 seats, but, in more than 50 seats, the number of African, Asian and Caribbean voters was greater than the winning party’s margin of victory. In other words, “the Black vote could make the difference,” says Woolley. “Jack Straw [then shadow home secretary] promised that if Black people voted Labour, he’d afford us a public inquiry into the death of Stephen Lawrence.”

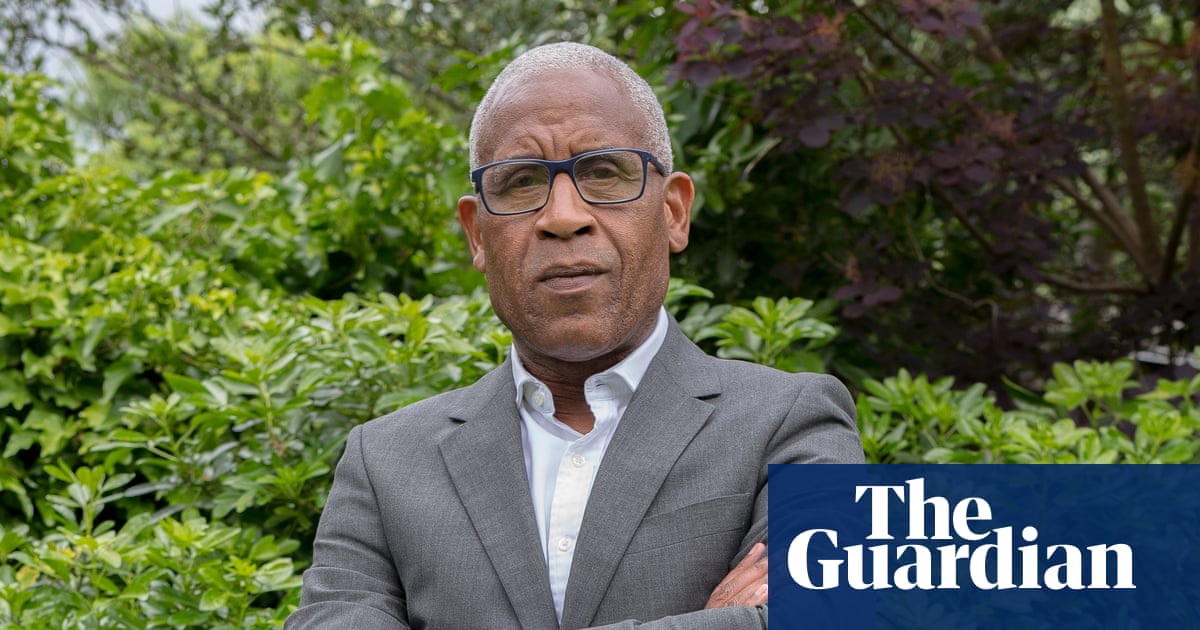

Twenty-five years on, markers of Woolley’s success are all around. The number of Black and minority ethnic MPs has increased to 65. In 2018, Theresa May chose Woolley to form No 10’s race disparity unit. The 59-year-old has worked with three prime ministers as well as civil rights leaders such as Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson. And in October, Lord Woolley of Woodford, who left school at 16, will become the first Black man to head an Oxbridge college, as the principal of Homerton College, Cambridge.

Speaking via Zoom early on a Wednesday morning from his home in Woodford, east London, Woolley is considered – content to leave long pauses as he chooses the right word. “It’s a wonderful opportunity to ensure that a great institution like the University of Cambridge can be a beacon for council house kids to aspire to,” he says. “I’m not averse to intervening to ensure there’s a pathway for working-class students – Black and white – to excel at Homerton College.

“Too often, we’ve looked for talent in a very narrow framework. When I was 16, me and my friends had to be smart to survive, but I had to go a very long way round for those skills to be recognised. My job now is to make sure that those ‘unpolished gems’ have a clear path.”

Alongside changing individual lives, Woolley has an eye on more fundamental shifts. “I hope we’re able to expand the limited view of what success looks like. Should our focus be on getting the double firsts or on being great innovators for social justice?”

Simon Woolley was born in Hinckley, Leicestershire, in 1961, but grew up in St Matthews, Leicester, with his adopted parents. “My mother was a childminder so our house was full of kids – between half a dozen and 10 at a time.”

Today, St Matthews is the most deprived part of the city. But when Woolley was young, most of the largely white, working-class residents on his council estate had jobs. Racism was rife, however, and the expulsion of Asians from Uganda and their exodus from Kenya had changed the demographics. “The local tectonic plates shifted dramatically and that empowered the National Front.” As a nine-year-old, Woolley remembers watching helplessly as a group of skinheads savagely beat an elderly Asian man. “As kids, we knew racism. We saw the skinheads, and when we grew up, we fought the skinheads.”

Woolley’s older brother, Mick, taught him to use his fists, in answer to racially motivated bullying in his primary school. “He said: ‘When this guy comes to pick on you again, whack him and whack him again.’ I learned how to be perceived as a great fighter. I wasn’t, but that’s what I had to do to protect myself.”

His upbringing gave him an acute antenna for the world around him. “Me and my brother would go to a Caribbean area to get our hair cut. We would go at nine in the morning and not leave until three in the afternoon. The whole time we’d sit, not saying a word, and listen to these men talk. I’d never been to Barbados, my homeland, so hearing these men say: ‘We might be free but the white men still owns our island’ helped me understand what I was seeing in Leicester.”

While “reprehensible levels of racism” were a fact of life growing up – including at the hands of the police – his white parents, Phillis and Dan Fox, who fostered then adopted him, also gave him “a unique perspective … I knew that white people could be won over and that the problem was a lack of understanding.”

He left school without A-levels. “For most working-class kids, their trajectory is decided for them at 11 years of age,” he says. “One path was a kaleidoscope of opportunities. The other was the leftovers. It’s only afterwards you see that you’ve been shunted down one path while other people are on another.

“In St Matthews, our aspirations were no greater than getting an apprenticeship. A lot of young people now would snap your hand off for a good apprenticeship, but we definitely weren’t thinking university.”

Instead, Woolley became a car mechanic – a job he enjoyed but for one thing: “Your nails would just get caked with dirt, which didn’t help when you wanted to go out and see the girls.” At 19, he moved south and into sales, from showers to coffee machines to advertising. He was so successful he could afford to buy his own house at 21. Yet something was missing, he says. “You get that quick buzz. But I knew there was a greater calling.”

A college access course led to a degree in politics and Spanish at Middlesex University, and travel to Latin America. Visiting Colombia, in the “days of Pablo Escobar and narco-democracy”, the politics bug fully bit. “I encountered people dying for their values. When I came back I said to myself: ‘I’m not going to get shot, I’m not going to get kidnapped. Nothing can stop me from changing the world.’”

On his return, Woolley joined Charter 88, a group that campaigned for electoral reform. It was influential but Woolley felt it was too easily ignored. “So many people felt powerless. We would march and sometimes we’d even tear down our own streets, but we were too far removed from the democratic process.”

Instead, his “eureka moment” was realising that “we needed to get every party vying for the Black vote. The Black struggle does not have the luxury of waiting for the perfect prime minister.”

OBV was formed in response and ran a succession of influential poster campaigns. During the 1997 general election, its posters featured the three main party leaders and their constituency phone numbers; John Major had to change his after a deluge of calls from Black voters. In 2015, OBV ran posters featuring the actor David Harewood and footballer Sol Campbell with white faces, encouraging people to vote. There were also mentoring schemes – the Bristol mayor, Marvin Rees, the Labour MP Clive Lewis and the Tory MP Helen Grant were all nurtured by OBV leadership programmes, says Woolley, who adds that he has “an excellent relationship with the vast majority of Black, Asian and minority ethnic MPs, from Sajid Javid to David Lammy”.

His ability to work with Labour and the Conservatives is reflected in his crossbench status in the House of Lords, to which he was appointed by Theresa May in 2018. “I marched on Downing Street against Windrush. But in regards to systemic racism, she got it,” he says. But as a Black man, it was not just his party politics he felt he had to compromise. “I’ve had to dramatically change my tone to be respected. I’ve lost my accent, which I’m a bit ashamed of.

“[As a Black man] having the moral high ground, even the intellectual high ground, isn’t enough. As a young activist, simply talking about racial discrimination would get me seen as an aggressor. We’re always judged by a different standard. Us activists have always known that when we point the finger at discrimination our reality will be vociferously denied.”

There are 65 ethnic minority MPs, but if parliament was truly representative, there would be 91. The political fortunes of the “young, gifted and Black” activists Woolley earmarked for success in 2007 also paints a complicated picture. Dawn Butler, probably the most successful, is currently without a role in the shadow cabinet, while Chuka Umunna did not “end up as the UK’s Barack Obama” as Woolley predicted he might. And perhaps the less said about Shaun Bailey’s campaign for mayor of London this year the better.

Meanwhile, the price ethnic minority politicians have to pay to enter politics remains depressingly high. “I’ve sat and cried with Diane Abbott as she’s shown me some of the hundreds of horrific messages she receives every day,” says Woolley. “Look, I want more people to come into politics from working-class backgrounds and Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds, but I have to be honest: it will be tougher for you.”

The 2016 EU referendum saw Woolley in the centre of his own storm after an OBV poster showed a Sikh woman and a skinhead on either end of a seesaw with the slogan: ‘A vote is a vote.’ It was claimed that the poster equated Brexit supporters with neo-Nazis. Woolley grows animated as he draws parallels between the xenophobia in 2016 and the culture wars of today. “It’s the same as the forces that deride Marcus Rashford as a communist because he dares to challenge institutional racism. It’s a classic modus operandi. Deny, deny and then whatever they’re calling you, you call them.

“The Black Lives Matter movement has given us the platform to have the greatest discussion ever about who we are as a nation. What were those young people essentially saying last summer? That the institutions built during the time when we enslaved Africans and colonised more than half the world are still here. It’s no surprise that the infrastructure built to that end still produces negative outcomes for those people from cradle to grave.

“Covid exposed those racial fault lines. The porters, the cleaners, the security guards: they’re disproportionately Black and brown. All you have to do is join the dots.”

Since standing down as chair of the race disparity unit’s advisory group in July 2020 (“I was told, crystal clear, that Boris Johnson wanted people that were ‘demonstrably his’”), Woolley has been dismayed by the rise of prominent Black and Asian politicians who “seek to deny the levels of systemic racism that exist today”. In the Guardian, he called the Sewell report into racial and ethnic disparities a “historic denial of the scale of race inequality in Britain” earlier this year.

The report, published in March, was widely condemned as divisive for asserting that “‘institutional racism’ is used too casually as an explanatory tool”. It also argued that “there is a new story about the Caribbean experience which speaks to the slave period not only being about profit and suffering”.

“We spent 50 years convincing society that systemic racial barriers exist and they need to be effectively dealt with for the benefit of everyone,” says Woolley. “That report took us back to the 1950s. When Tony Sewell says there’s a good story to be told about slavery, it shows that we are not all homogeneous. Not all skinfolk are our kinfolk.”

He is, he says, “heartbroken” by a discussion around white privilege that, he believes, seeks to “pit white working-class kids against poor Black kids”. Kemi Badenoch, the equalities minister, for instance, has said that teaching white privilege, for instance, “reinforces the notion that everyone and everything around ethnic minorities is racist”.

“One of my greatest regrets,” says Woolley, “is fighting for Black and brown faces in high places, only to weep when I hear Kemi Badenoch go on national TV to say our children are being taught that Black people are good and white people are bad. Discriminatory factors have been writ large in education. The simple fact is every Black parent knows their child will do better when their exam paper is marked blindly.

“For me, Operation Black Vote has to redouble its efforts to nurture Black and brown leaders that have a sense of integrity. We want to see people who look like us – but not at any price.”

Woolley was knighted in the Queen’s birthday honours in June 2019 and made a life peer shortly after being made a knight of the Thistle. “I never wanted to accept an honour with the word ‘empire’,” he says. Yet it has not stopped prejudice in the House of Lords library. “Three times in the space of three months, a lord would tap me on the shoulder and say: ‘Can you help me with the photocopier?’ It doesn’t matter where I am or what I’m wearing. I still don’t get seen as one of them.”

Today, Woolley hopes education can succeed where politics failed. “It’s not about building back better because back wasn’t great. It’s about unleashing a new Great Britain in which all of us have the opportunity to excel. I believe we can do better. Waking up in the morning and believing that you can change the world is the greatest honour.”

Source: The Guardian

Powered by NewsAPI.org