We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I by Raja Shehadeh review – family and politics collide - 5 minutes read

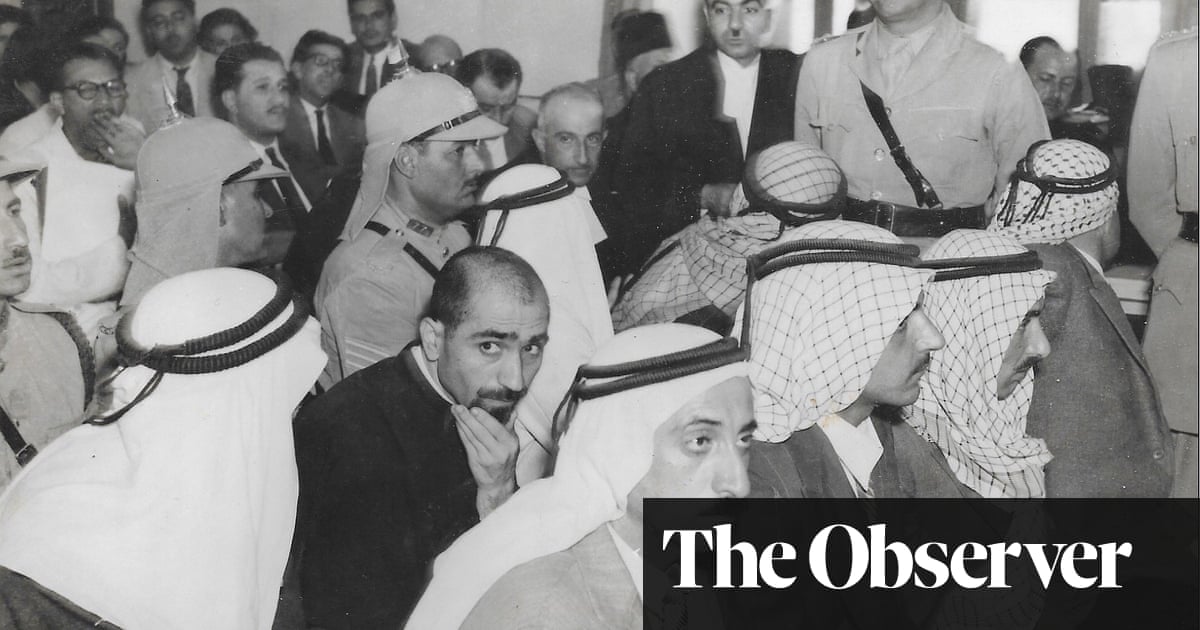

Aziz Shehadeh (centre back) in court following the assassination of Abdullah, king of Jordan, 1951. Photograph: Raja Shehadeh Autobiography and memoir We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I by Raja Shehadeh review – family and politics collide Raja Shehadeh and his father, Aziz, both Palestinian lawyers, had different views on how to achieve statehood for their nation. Raja recounts their struggle, and his father’s murder, in this highly readable memoir

Raja Shehadeh, the well-known Palestinian author, was born in 1951 in the West Bank town of Ramallah (under Jordanian rule), three years after Israel was founded. His father, Aziz, was born in Bethlehem in 1912 (then part of the Ottoman empire), five years before the Balfour declaration paved the way for the success of the Zionist movement and the Nakba – the Palestinian catastrophe caused by the creation of the Jewish state.

Dates, birthplaces and governments matter a lot in this story. It is about the strained relationship between a father and his son, told by the son, against the background of one of the most intractable and divisive conflicts on earth. They were both intelligent and successful lawyers, so the account and the documentation are impressively comprehensive.

Efforts to resolve that conflict have failed since 1993 when the Oslo Accords were signed. Subsequent attempts have not succeeded in ending the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem; the Gaza Strip, under the rule of the Islamist movement Hamas, remains besieged by Israel. The current assumption – based on public opinion on both sides, as Raja notes – is that there will never be a two-state solution. Israel is increasingly (and controversially) viewed as an “apartheid state”.

Aziz had to flee the port city of Jaffa in 1948 and was murdered in 1985, when he was 73, outside his Ramallah home by a Palestinian who collaborated with Israel. So Raja goes through his late father’s papers and reconstructs his legal and political activities in this short book – the latest in a series of highly readable personal memoirs he has published covering different aspects of endless Israeli rule.

Aziz’s death was a life-changing event for Raja: “For years I lived as a son whose world was ruled by a fundamentally benevolent father with whom I was temporarily fighting,” he writes. “I was sure that we were moving, always moving, towards the ultimate happy family and that one day we would all live in harmony. When he died before this could happen I had to wake up from my fantasy.”

Raja begins by recounting a rare occasion when he and his father cooperated in writing a legal brief objecting to an Israeli plan to build a series of roads across the occupied West Bank in 1984 to connect illegal Jewish settlements to one another (and to Israel itself), completely ignoring Palestinian residents. Aziz asked the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) to support the project, which it refused to do, because at that time its overall strategy was to liberate the entire country “between the river [Jordan] and the [Mediterranean] sea”.

By 1980 Aziz had given up on his idea – then rejected by Israel and Arab states – for an independent Palestinian state next to Israel as a workable solution to the conflict. As a young man Raja failed to recognise his father’s courage. Nor did Aziz appreciate Raja’s efforts to campaign for human rights, via the famous Al-Haq organisation his son helped found.

This book is full of retrospective thought-provoking parallels between his own experience and his father’s: describing the Jordanian Arab Legion, commanded by the “English bully” Glubb Pasha, taking over the West Bank in 1948, Raja is reminded of Israeli military occupation 19 years later. In both cases it was declared that Mandatory-era British laws in force would remain until amended or abolished. But that never happened, giving Jordan and Israel the “right” to oppress the Palestinians. In 1948 Aziz was arrested, along with others who planned to return to their homes in Jaffa.

Raja is very critical of the king of Jordan, Abdullah, who annexed the West Bank in 1950 and negotiated secretly with the Zionists and the British. Abdullah was assassinated when visiting the al-Aqsa mosque in East Jerusalem a year later and Aziz represented three of the Palestinians accused of killing him, but because of that he incurred the regime’s unwavering hostility.

Raja describes a journey with his father, in the aftermath of 1967, to visit a plot of land, south of Jaffa, that he had bought before the Nakba. Aziz didn’t utter a single word or show any emotion. “Was it rage or embarrassment that he felt? I suspect it was more likely shame at how badly his generation had failed, losing their land to Israel and never achieving the return he had worked so hard to realise.”

In the big picture of their relationship, Aziz and Raja disagreed profoundly about how to secure Palestinian statehood. Raja believed it could be done by invoking human rights, whereas Aziz (at least until shortly before his death) was dealing not with the consequences but with the core issue of ending the occupation, which these days seems virtually impossible. So perhaps eventually father and son would have come to agree.

Source: The Guardian

Powered by NewsAPI.org