Why liberalism and leftism are increasingly at odds - 11 minutes read

Last week, the presidents of Harvard, Penn and MIT testified before Congress. In a clip widely shared by the hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, the presidents backpedaled and offered a series of legalistic defenses when asked by Rep. Elise Stefanik about whether calling for the genocide of Jews violated their respective bullying and harassment policies.

You might not expect Stefanik, a once-moderate Republican who became a loyal Trump supporter, to garner much sympathy from liberals. But there was initially an intensively negative reaction to the presidents from nearly everyone save the left wing. That included people who I’d normally consider to be partisan Democrats who rarely criticize their own “team” — indeed, even the White House condemned the presidents. By the weekend, Liz Magill, the president of Penn, resigned under pressure from Ackman and the board.

Part of the problem for Magill, Harvard president Claudine Gay and MIT president Sally Kornbluth is that you could criticize them from several different directions: because they didn’t sufficiently condemn anti-Semitism, because they didn’t sufficiently defend free speech, and because the hearing was a PR disaster. That can lead to some weird coalitions — such as between people who want to see additional consideration for Jewish students within university speech codes and DEI frameworks, and others who want to see those frameworks dismantled.

Eventually, the politics retreated to more of a familiar Blue Team vs. Red Team standoff, because Ackman — not a sympathetic figure to begin with — overplayed his hand in too aggressively looking for scalps and because he was joined in this by conservatives like Stefanik and Chris Rufo that the Blue Team dislikes. So Gay and Kornbluth are safe for now, although Gay also faces credible plagiarism accusations.

Still, as much as I think too much attention is often paid to elite universities, I’m fascinated any time that new political fault lines are potentially exposed. A New York Times headline, for instance, expressed surprise that “many on the left” were sympathetic to Stefanik. But this isn’t properly described as a battle between left and right. Rather, it’s a three-way tug-of-war between the left, the right, and liberals.

The essay “Why I Am Not A Conservative” by the Nobel Prize winning economist F.A. Hayek is a must-read for anybody who wants to understand how liberalism was traditionally defined in the Enlightenment political tradition and how the term came to be used in a rather different way in the United States. To simplify: liberalism is a political philosophy that’s centered around individual rights, equality, the rule of law, democracy, and free-market economics. There are many flavors of liberalism that emphasize these components in different ratios, running from more libertarian variants to others that see a much larger role for government.

In Europe, liberalism arose in opposition to a more conservative social hierarchy — usually, feudal monarchies backed by incredibly powerful churches. So if you were looking toward Europe, it made sense to think of liberalism as denoting change. As Hayek points out, however, the United States was founded on liberal, Enlightenment ideas. Appeals to classical liberalism are in some ways appeals to American tradition, therefore. Nonetheless, left-wing “American radicals and socialists” began calling themselves “liberal” because they wanted a departure from these traditions, Hayek wrote. Thus, in the United States, we wound up in a confusing position where “liberal” can either be a synonym for “left-wing” or can refer to European-style liberalism.

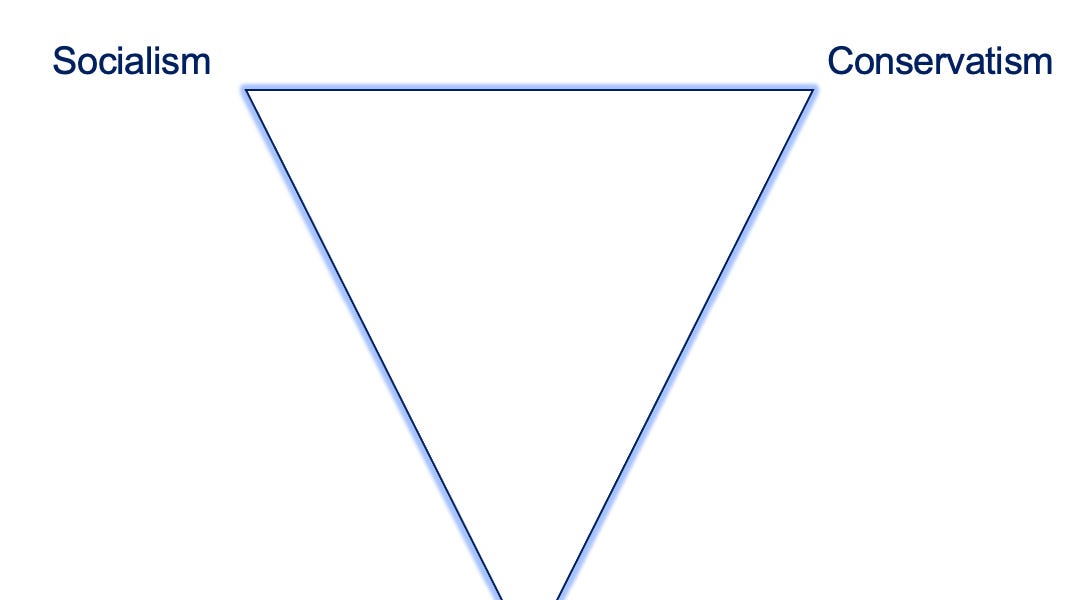

The mainstream media almost always uses the former definition (“liberal” just means left). However, in Hayek’s view — and mine — we should return to the original definition of liberalism. That’s because liberalism describes something distinctive. It doesn’t suffice to view liberalism as a halfway point between socialism and conservatism, Hayek thought, because in important ways it differs from both, namely in its elevation of individual rights and suspicion of central authority. Instead, he imagined a triangle that looked like this, with socialism and conservatism as two flanks and liberalism in the third corner:

In the years following the fall of the Soviet Union, the distinction between “socialism” and “liberalism” gradually came to seem less necessary. Instead, the connotation of “socialism” shifted from “something adjacent to Communism” to “countries like Sweden with high taxes, free health care and tasteful furniture”. If you’re a moderate liberal like me, then Sweden-style democratic socialism might be somewhat to the left of your ideal point. But it’s still well within the acceptable range of outcomes — particularly since Sweden is a canonically individualistic, culturally liberal, WEIRD country.

However, the purpose of this essay is to argue that socialism now has a worthy successor in the Hayekian triangle — what for purposes of this essay I’ll call Social Justice Leftism (SJL) but is more commonly referred to as “wokeism”.

Proponents of SJL usually dislike variations on the term “woke”, but the problem is that they dislike almost every other term as well. And we need some term for this ideology, because it encompasses quite a few distinctive features that differentiate it both from liberalism and from traditional, socialist-inflected leftism. In particular, SJL is much less concerned with the material condition of the working class, or with class in general. Instead, it is concerned with identity — especially identity categories involving race, gender and sexuality, but sometimes also many others as part of a sort of intersectional kaleidoscope. The focus on identity isn’t the only distinctive feature of SJL, but it is at the core of it.

SJLs and liberals have some interests in common. Both are “culturally liberal” on questions like abortion and gay marriage. And both disdain Donald Trump and the modern, MAGA-fied version of the Republican Party. But I’d suggest we’ve reached a point where they disagree in at least as many ways as they agree. Here are a few dimensions of conflict:

SJL’s focus on group identity contrasts sharply with liberalism’s individualism.SJL, like other critical theories that emerged from the Marxist tradition, tends to be totalizing. The whole idea of systemic racism, for instance, is that the entire system is rigged to oppress nonwhite people. Liberalism is less totalizing. This is in part because it is the entrenched status quo and so often is well-served by incremental changes. But it’s also because liberalism’s focus on democracy makes it intrinsically pluralistic.SJL, with its academic roots, often makes appeals to authority and expertise as opposed to entrusting individuals to make their own decisions and take their own risks. This is a complicated axis of conflict because there are certainly technocratic strains of liberalism, whereas like Hayek I tend to see experts and central planners as error-prone and instead prefer more decentralized mechanisms (e.g. markets, votes, revealed preferences) for making decisions. Finally, SJL has a radically more constrained view on free speech than liberalism, for which free speech is a sacred principle. The SJL intolerance for speech that could be harmful, hateful or which could spread “misinformation” has gained traction, however. It is the predominant view among college students and it is becoming more popular in certain corners of the media and even among many mainstream Democrats.Since the October 7 Hamas terrorist attacks and Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza, I’ve sometimes heard people express surprise that other people they knew (whether in their real lives or on social media) turned out to be more pro-Israel or pro-Palestine than they thought. To me, it’s almost been the opposite: the reactions have been highly predictable. Leftists tend to take the Palestinian side, and liberals the Israeli one; I think it was easier for me to see this because I’ve long been sensitive to the difference between leftists and liberals. Furthermore, these views tend to be correlated with other issues that divide liberals and leftists, such as free speech and even COVID restrictions.

Why is this? In some sense maybe it shouldn’t be this way — there should be more heterodox pro-Israel leftists and heterodox pro-Palestine liberal centrists. From a liberal’s perspective, however, especially from a Jewish liberal’s perspective — which is to say my perspective — it’s easy to see why October 7 was so divisive.

SJL has an elaborate matrix of racial and identity categories, which Jewishness has always fit awkwardly into. Jewishness is both an ethnicity and a religion. Jews in the United States are quite successful despite the extremely high historic incidence of anti-Semitism, including of course the Holocaust. Meanwhile, there’s the distinction between the Jewish people and the Israeli state. And race and ethnicity within Israel are complicated; many Israeli Jews are Mizrahi, meaning they have ancestry from the Middle East rather than Europe. So Jewishness is an edge case that makes the entire identity politics architecture look kind of dubious, if we’re being honest.

So what was the reaction from SJLs after an anti-Semitic terrorist attack that killed thousands of Jews? Well, there certainly wasn’t much sympathy. Instead, we got Harvard students defending Hamas. We got people tearing down portraits of hostages, hanging Palestinian flags on menorahs and polls showing an alarming rise in Holocaust denial among young people.

Now, if liberal Jews didn’t get any SJL sympathy, maybe we’d at least get some reconsideration of illiberal SJL attitudes? You know, university presidents saying: Yeah, you’re right, actually the world is a complicated place and probably it was a bad idea to divide people into 16 intersectional categories of oppressed and oppressor, good and evil, and now that I think about it I can even see how this could contribute to anti-Semitic hatred — sorry about all that!

Nope, not that either. Instead, the compromise Jews were offered — begrudgingly at every turn — was that we might have our scores slightly raised in the DEI spreadsheet and that universities would crack down on pro-Palestinian speech. As a liberal Jew, I don’t want any of that, which just entrenches the SJL view of the world.

Now, for me, I’m good at decoupling, so the intense anger I feel at some of this doesn’t translate into having any particularly radical view about what should actually be done in the Middle East, or for that matter something like who I plan to vote for as president. But it’s all been incredibly polarizing. Many people are going to be radicalized. Certainly both Jewish people and Muslims will be, in ways that will make life tougher for Joe Biden.

But also, I suspect that an increasing number of liberals will a) more clearly recognize that they belong to a different political tribe than the SJLs and even b) will see SJLs as being just as bad as conservatives. And this will cut both ways; some SJLs will regard liberals as just as bad as conservatives — enough so that they might even be willing to deny a vote to Biden. All of this is quite bad for the progressive coalition between liberals and the left that’s won the popular vote for president four times in a row.

Now, maybe the progressive coalition will get lucky because MAGA-flavored conservatism remains such an unappealing alternative to people outside the Trumpiest 30 percent of the country. But both liberals and SJLs might find temptations: for instance, liberals will be tempted by MAGA pledges to dismantle DEI on campus, even if conservatives are also quite terrible about protecting academic freedom. Meanwhile, one of Hayek’s points was that socialists and conservatives shared a tolerance, if not even a reverence, for authoritarianism. SJL and MAGA could align there as well. SJL has already moved away from the liberal tradition of entrusting people to make their own decisions — think of the since-scuttled Disinformation Governance Board, or the draconian COVID restrictions on college campuses. If Trump wins next year, this tendency will get worse, and SJLs may more openly question whether democracy works at all.

Share

The old left-right coalitions have long been under strain as America has moved away from materialist politics to the politics of cultural grievance. The clearest manifestation of this has been intense polarization based on educational attainment (the more years of schooling, the more likely you are to vote Democrat). If, however, higher educational institutions and the ideas associated with them continue to become more and more unpopular, I’m not sure what happens next.

In the short run, this may be excellent news for conservatives — most voters aren’t college graduates to begin with, and even college-educated liberals are increasingly coming to see SJL ideas as cringey and unappealing. In the long run, as anger over October 7 and the pandemic era fades, conservatives will have to offer a more appealing alternative, as the current version of the GOP espouses lots of highly unpopular ideas of its own and only the most polarizing, MAGA-iest Republicans can reliably win Republican primaries. The past 20 years of American politics have mostly been characterized by stability: the 2020 electoral map didn’t look much different than the 2000 one. If the progressive coalition is breaking up, the next 20 could be much more fluid.

Source: Natesilver.net

Powered by NewsAPI.org