Jim Clyburn’s Long Quest For Black Political Power - 20 minutes read

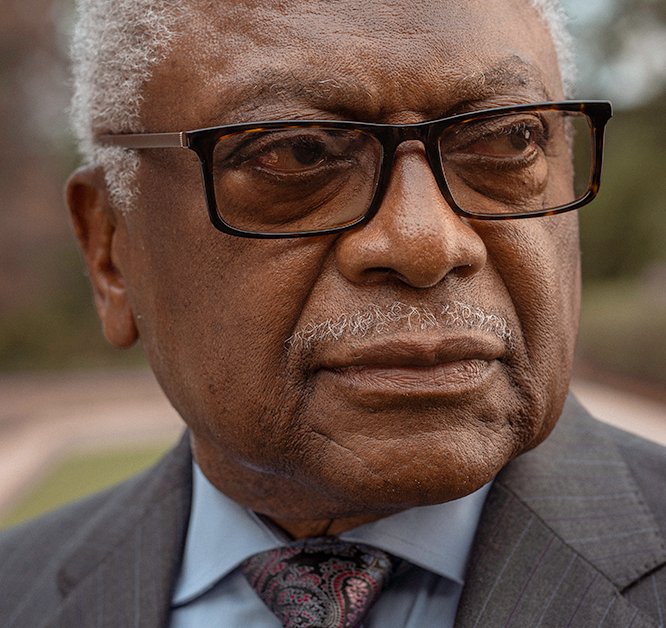

On a sticky-hot night in the South Carolina capital, Representative Jim Clyburn takes the outdoor stage at his late-night afterparty. Clyburn—the 82-year-old House Democratic whip, maker of Presidents, and highest-ranking Black man in Congress—has a message of hope for dark times. “In spite of all its faults, there ain’t a better country to be living in,” he says in his imposing baritone. “And you and I will have to do our jobs out here at the polls to save this country from itself.”

Of the hundreds in attendance this June evening at the EdVenture Children’s Museum, some have come from the fundraising dinner down the street for the South Carolina Democratic Party, where the first Black woman Vice President was the keynote speaker. But many have not. Clyburn throws this free bash so those who can’t afford to attend a fundraiser have a way to participate. Wearing a navy suit and holding a mixed drink, he’s joined on the patio by Congresswoman Shontel Brown of Ohio, who credits Clyburn’s endorsement for her victory in a special election last year, coming from 35 points behind to defeat a Bernie Sanders–backed progressive.

“It’s no coincidence that his initials are J.C.—you can reference the story of Lazarus by another J.C. in the Bible,” Brown tells me. “When you think about folks like myself and Joe Biden, who looked like they didn’t have a chance to win, our J.C., Jim Clyburn, gave us his stamp of approval and resurrected what had been perceived by many as an impossible victory.”

Clyburn is in his element, surrounded by the vast political network he’s nurtured. Brown got her start in a Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) training program Clyburn helped create; her boyfriend is Clyburn’s political adviser Antjuan Seawright. The entire afterparty—which will turn into a raging dance-off before the night ends—is packed with people Clyburn has prodded into politics: local party officials, members of district executive boards, city council members from across the state, county auditors and coroners. “I thought politics was all deceitfulness and lying, and I didn’t want any part of it,” Anthony Thompson Jr., a thin Columbian in a salmon-pink suit, tells me. “He made me see that you have to be part of the system to make change.” After training in one of Clyburn’s mentorship programs, Thompson now serves as second vice chair of the local party and started its first disability caucus.

Clyburn’s influence in Democratic politics is as far-reaching as it is unsung. Today, he’s widely credited with swinging the 2020 presidential primary to Biden, rescuing the flailing campaign with a well-timed endorsement that buoyed him to a 30-point victory in South Carolina—and extracting a promise to name the first Black woman to the Supreme Court. That wasn’t even the first time Clyburn helped make a President: he was instrumental to Barack Obama’s victory in 2008, and before that played a key role in putting South Carolina near the top of the primary calendar in the first place. His friends serve in top posts across the Administration and party. Democratic National Committee chairman Jaime Harrison, who Clyburn pushed for the post, and who was just 29 when Clyburn made him the first Black executive director of the House Democratic caucus, says a large percentage of Black Americans in politics today can trace their positions to Clyburn.

A few months ago, when numerous congressional Democrats were clamoring to chair the high-profile select committee investigating the Jan. 6 riot, it was Clyburn who urged Speaker Nancy Pelosi to name his best friend, Congressman Bennie Thompson—native of Bolton, Miss., graduate of historically Black Tougaloo College—its chairman. In the whispering campaign that ensued, Clyburn sensed a familiar dynamic. “A lot of people wanted to be chairman,” Clyburn tells me. “And quite frankly, nobody will admit to this, but it’s the same thing I had when I ran for whip. A Black guy from Mississippi, ain’t from an Ivy League School—they won’t say it, but they think it: ‘He can’t chair this.’” Pelosi ignored the whispers, and Thompson has been widely praised for his coolheaded handling of the committee’s hearings, proving what Clyburn knew all along: “Bennie is perfect for this,” Clyburn says. “He’s unflappable, and he ain’t searching for the limelight. He’s just doing his thing.”

The episode bore all the hallmarks of Clyburn’s style. As usual, he was quick to suspect a Black person wasn’t getting his due, and quick to do something about it. As usual, he pulled strings to arrange the outcome he thought best for his party and country. As usual, he did not seek public credit; as usual, the impact was notable. From poverty relief to funding for historically Black colleges to rural broadband, he’s the source of many significant policy achievements, but he is more often found behind the scenes than on the dais.

This quality as much as anything has put him at odds with today’s left. To a rising generation of activists, Clyburn’s penchant for incrementalism and backroom dealing represents complicity with an intolerable status quo at a moment when urgency is required. Campaigning for Brown and the conservative Democrat Henry Cuellar against more liberal candidates, he’s been called a corporate sellout and worse, accused of doing the bidding of his donors in defense contracting and the pharmaceutical industry. At a campaign event in Charleston in May, he was heckled by a far-left primary opponent over reparations. “We need those who are willing to fight fervently for Black people that are not so committed to the establishment,” says Amara Enyia, policy and research coordinator for the Movement for Black Lives. “Clyburn was very instrumental in influencing people’s decision to vote for Biden. As we look back on that now, people are really wondering, OK, this was supposed to be the best decision. How has that manifested in my life?”

In our interviews, I ask Clyburn his thoughts on the status and trajectory of Black political power in America. Fourteen years ago, the election of the first Black President vindicated his abiding belief in Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, but today he is less sanguine. Over the course of his six decades in politics, from 1960s sit-ins to the heights of congressional leadership, Clyburn has seen many things change for the better. But these days the momentum seems to have shifted. The Black Lives Matter movement drove unprecedented millions into the streets but did not succeed in spurring Congress to pass police reform or voting-rights legislation. White supremacy and racial dog whistling seem ascendant; 10 Black people were killed at a Buffalo, N.Y., supermarket in May by a white gunman who allegedly targeted them for their race. A school district in Pennsylvania, Clyburn notes, recently banned children’s books on King and Rosa Parks. “If that ain’t Hitlerism, tell me what is,” Clyburn says. “That’s what this country is coming to.”

Is the point of liberation to not be shut outside any longer, to gain access to the levers of power? Or is it a fool’s game to try to win by the rules of a system designed to oppress? “Progress in this country has never moved on a linear plane,” Clyburn says. “It goes forward for a while. And then it goes backward for a while.”

The following morning, Clyburn sits in a back room of the convention center where the state party is holding its annual meeting, eating a sugar cookie and pouring a bottle of Diet Coke into a plastic cup of ice. The tension between outside passion and inside power is one as old as protest itself, and was a perpetual point of contention in the civil rights movement Clyburn came up in. His own father thought his youthful militancy was too aggressive. But today, at a crucial moment for racial justice in America, Clyburn frets that the balance is out of whack—that too many seem content to call attention to problems without getting into the trenches to fix them.

“You know, this party of ours is catching so much flak, because there’s this contest: How many people get the most hits on social media? How many people get the biggest headline?” he says. “One guy is running against me right now in the primary, saying I’m not progressive enough. Show me one thing in my record. I get A ratings from all the labor unions. I get an A rating from the NAACP. Where am I not progressive? I’m not progressive to them because I don’t call people names. Because you ain’t gonna see me on TV yelling at somebody, trying to get a headline. I spend my time trying to figure out how best to hold on to this majority and get things done. They’re having a contest on who can yell the loudest.”

Clyburn was born in 1940 in Sumter, a racially divided town of 10,000 in central South Carolina. His father was a fundamentalist preacher, his mother a beautician and entrepreneur. Both fought against Jim Crow and encouraged their three sons to dream beyond the limitations placed on them. In 1960, as a student at South Carolina State College and leader in the newly founded Congress of Racial Equality, Clyburn led a march of 1,000 students through Orangeburg to demand the desegregation of local establishments. Officers commanded the quiet, orderly marchers to stop “disturbing the peace,” but said nothing to the howling white mob pursuing them. The police turned fire hoses on the protesters and slammed Clyburn into a cruiser; it took all his self-control to maintain his commitment to nonviolence as 388 marchers were arrested.

With the local jails full, some were housed for days in an outdoor stockade, wearing wet clothes in freezing weather, passing around cigarette lighters to warm their hands. As Clyburn waited at the courthouse for his bond to be posted, a petite coed offered him a hamburger. They were married 15 months later. (Emily Clyburn, his closest confidante and toughest critic, died in 2019.)

But his impulse was always to become part of the system. In 1970, Clyburn helped John West, a racially moderate white Democrat, secure the Black vote in his gubernatorial run against a Republican backed by the segregationist Senator Strom Thurmond. After he won, West appointed Clyburn to chair South Carolina’s newly created Human Affairs Commission, an agency charged with mediating racial disputes in the wake of desegregation and the Civil Rights Act. At 30, Clyburn was the first Black man to serve in the state cabinet, managing a staff largely composed of older white people.

Clyburn was perpetually at the center of a firestorm, simultaneously beset by Black activists who thought he was too compromising and white conservatives determined to undermine and ultimately abolish the commission. When a young Black man killed in a hit-and-run was rumored to have been murdered and castrated, Clyburn authorized an exhumation and autopsy that showed he was not, then castigated the rumor-mongering activists for needlessly dividing the community. When white cadets at the Citadel military academy terrorized a Black classmate, dressing in white sheets and waking him in the middle of the night with a burned paper cross, Clyburn defended their punishment even though it fell short of expulsion. “I not only wanted to advance the interests of Black people in the state, but I wanted also to be Exhibit A in the case for including more African American executives in state government,” Clyburn wrote in his 2014 memoir, Blessed Experiences: Genuinely Southern, Proudly Black. When he left the post after 18 years, he was under no illusion he had solved the problem, but felt that “we had created an imperfect reality where there had previously been only an idealistic dream.”

The work was controversial—and dangerous. In the 1980s, when Clyburn began advocating for the removal of the Confederate battle flag that flew over the state capitol, he spent five years under police protection for the threats he received. The situation came to a head in 2000, when Clyburn helped broker a compromise between the NAACP and the Republican state legislature to place the flag in a less prominent spot on the capitol grounds. But at the last minute, the NAACP pulled out and called the deal unacceptable. The legislature retaliated by putting the flag in an even more conspicuous spot. By refusing to compromise, the activists ended up worse off than they started. For years, Clyburn and the NAACP continued to trade barbs. (In 2015, after nine parishioners were murdered at a Black church in Charleston by a young white supremacist, legislators finally removed the flag.)

Read More: Jim Clyburn: How to Take Down the Confederate Battle Flag Once and For All.

In 1992, having already run for state and local office unsuccessfully three times, Clyburn decided to seek the state’s newly created majority-Black congressional seat. This time, he defeated four other well-qualified Black candidates by a wide margin, becoming the first African American to represent South Carolina in nearly a century. The first bill he authored created a new federal courthouse named after his childhood hero and mentor, the civil rights attorney and judge Matthew J. Perry, over the objections of Clyburn’s new congressional colleague Thurmond, who wanted it named after himself. Clyburn leveraged his relationships with Republicans to overpower Thurmond while using his vote on other issues as a bargaining chip to get the fiscally conservative Clinton White House to fund the project. On another occasion, he managed to secure a coveted slot on the Appropriations Committee—then voluntarily gave it up in exchange for votes on other priorities.

As a result of gambits like these, Clyburn had plenty of favors to call in when he ran in 2003 for a position in House leadership. With the unanimous support of the CBC, which he had chaired, Clyburn won in a rout. In 2006, he became the second Black majority whip in history. One white colleague, he wrote, “gave an emphatic yes when I asked for his vote, but expressed some reticence about putting a whip in a Black man’s hand.”

Of the more than 12,000 Americans who have served in Congress, just 175 to date have been Black. Clyburn’s ascension to congressional leadership paved the way for other Southern Blacks, Bennie Thompson tells me. “If you were from the South, they assumed that, because you spoke a little slower, that had something to do with your brain,” Thompson says. “We came from the back of the bus to the front of the bus with Jim Clyburn in the driver’s seat.”

Former President Obama once described Clyburn as “one of a handful of people who, when they speak, the entire Congress listens.” His persona is a curious mix of gravitas and levity, with little in between; with his booming voice and impish smile, he always seems to be simultaneously half-joking and deadly serious. In Washington, he dines most nights at the private National Democratic Club with Thompson; Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Secretary Marcia Fudge, a former Congresswoman whom Clyburn lobbied Biden to put in the Cabinet; and Cedric Richmond, a former Congressman and Clyburn protégé who recently departed a top Administration position. Many significant decisions on the 2020 campaign and in the Biden White House have been hashed out at those dinners, Richmond tells me. “We fix problems, we cause problems—we do a little bit of everything,” he says.

Clyburn has been aggressive in cashing in the political capital he accrued by powering Biden to victory, sometimes irking the White House in the process. When a Supreme Court vacancy opened up this year, Biden moved to make good on his promise to Clyburn to appoint a Black woman. Clyburn publicly lobbied for South Carolina judge Michelle Childs, but Biden picked Ketanji Brown Jackson, and named Childs to the prestigious D.C. Circuit Court instead. Clyburn originally urged Biden to appoint Fudge to a different Cabinet post, Secretary of Agriculture, instead of HUD, which Fudge publicly derided as a stereotypically Black position.

“I was flat out pushing her for Ag,” Clyburn tells me—a slot in which the Ohioan would have been positioned to address the rural poverty that affects so many of his constituents. Biden, Clyburn says, called him one night and implored him to back off; the President wanted to appoint his friend Tom Vilsack, who had served as agriculture secretary under Obama. But Clyburn harbored a grudge against Vilsack for his hasty 2010 firing of department official Shirley Sherrod based on a deceptively edited video. (Clyburn had served in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee with Sherrod’s husband Charles Sherrod.) He publicly criticized Obama for the decision, for which Vilsack later apologized. During their conversation last year, Clyburn tells me, Biden asked him to talk with Vilsack and see if they could come to an understanding. “And so I did agree to talk with him,” Clyburn recalls. “And then I relented.”

“Jim is there to do the work. He is a person that would rather get things done than worry about who gets the credit,” Fudge tells me. “What we have now is so many people who believe that the whole movement to fight for justice started with them. They need to realize that people like Jim Clyburn have been on the battlefield for a long time.”

Clyburn is “instrumental” to the Democratic caucus, says Speaker Nancy Pelosi, in ways that are often not publicly apparent. His official job is to count votes, but he also speaks up for Black priorities at the leadership table and mediates between party factions. Last year, it was Clyburn who brokered a delicate agreement between moderate Democrats and the CBC to ensure that Biden’s infrastructure and spending bills could both pass after prolonged infighting, according to Clyburn and two others who were in the room. He then refused to appear at the press conference announcing the deal, he tells me, because he felt his friend Joyce Beatty, the current chair of the CBC, needed the plaudits more

Read More: Nancy Pelosi Doesn’t Care What You Think of Her. And She Isn’t Going Anywhere.

“Some of these fights are long ones, and you have to recognize that you may not have immediate success, but you have to have constant focus,” Pelosi tells me. “Clyburn is a person like that—though he prefers immediate success.”

When Clyburn held his 27th annual World Famous Fish Fry in June 2019, nearly the entire Democratic presidential field schlepped to Columbia to make their pitch to the early primary state’s predominantly Black electorate. The visit doubled as a chance to kiss Clyburn’s ring, even though most suspected his old friend Biden had the inside track to his endorsement. From a massive outdoor stage, 21 candidates addressed an overheated, jostling crowd. More than 4,000 pounds of fish were consumed.

This year, after two years of COVID-19 cancellations, Clyburn decided against holding the fish fry in its full glory, replacing it with a number of smaller events, such as today’s low-country boil in Columbia’s historically Black Greenview neighborhood, where he has long made his home. Some saw the potential end of the tradition as a sign Clyburn is making plans to retire. He tells me he is, but won’t say when, and plans to serve the two-year term for which he’s currently running, even if Democrats lose the House.

The contrast with the 2019 festival is stark: a few dozen locals sitting in folding chairs in a half-empty community-center gymnasium, eating the mix of shrimp, corn, and potatoes from a few steam trays at the side of the room. Media outlets from all over the world covered the presidential event, but this time there are just a few local reporters in attendance. Taking questions on the way into the gym, Clyburn delivers an impromptu lecture on political communication. Democrats’ biggest challenge, he opines, is “spending a little more time understanding people’s habits, people’s aspirations, understanding how to talk to people on their own terms.” The party, in other words, sounds out of touch with regular people. Clyburn has been harshly critical of the “defund the police” slogan embraced by some on the left, comparing its politically damaging resonance to the “burn, baby, burn” chant of the 1960s.

Many liberals today feel let down by congressional Democrats, who they accuse of offering little but thoughts and prayers as mass shootings proliferate, Roe v. Wade is overturned, and the climate burns. Clyburn’s primary opponent, a 37-year-old teacher named Gregg “Marcel” Dixon from rural Ridgeland, tells me Black Americans are worse off today than they were during the civil rights movement because leaders like Clyburn have sold them out. “How much time are Black people supposed to wait for progress?” Dixon says. Running on a platform of massive reparations that would allow African Americans to build institutions separate from white society, Dixon got about 4% of the vote in the June primary.

Inside the gym, Clyburn tells the crowd he’s tired of hearing that Democrats haven’t done anything. “We need to talk more about our accomplishments,” he says, brandishing a flier that lists some of the projects he’s gotten funded: money for Black colleges and community health facilities, hospital upgrades and veterans centers, rural broadband. The $20 million Lake Marion Regional Water Agency, which brought potable water to much of his district for the first time. Heritage-preservation corridors and national parks. Affirmative-action provisions for government hiring. His “10-20-30” funding formula, which specifies that 10% of federal spending be reserved for areas where at least 20% of the population has been below the poverty line for 30 years or more. The formula now applies to 15 appropriations accounts—little provisions tucked into bigger bills that can have a major impact. Headway, not headlines, as he likes to say.

This is the change Clyburn practices and preaches, the unsexy work of improving people’s lives, little by little, and keeping at it through setbacks. No single piece of legislation, no revolution, not even a single election can solve problems that have mounted through centuries. Clyburn has never believed that progress is guaranteed, but he’s all too familiar with the persistent illusion. “I’ve heard it said so often: ‘Well, all we have to do is have a few funerals,’” he tells me. “‘The younger white people think differently.’ No, they don’t. No, they don’t.”

In 1985, Clyburn traveled to Dayton, Ohio, to speak at a conference also featuring Clarence Thomas, then President Reagan’s chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission—the federal agency with jurisdiction over state commissions like the one Clyburn headed. Clyburn was there to speak in favor of affirmative action, which he knew Thomas opposed. Rather than stage a confrontation, he tailored his remarks to appeal to Thomas, citing their shared Southern backgrounds and quoting Lincoln. A more aggressive speech would have delighted the national media in attendance—but might have alienated an important federal agency whose help Clyburn was likely to need in the future.

Clyburn thinks often about the contrast in worldviews between himself and Thomas, now the archconservative senior Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, he tells me in his D.C. office. In interviews and a memoir, Thomas has recounted being sternly lectured by the grandfather who raised him never to look a white person in the face. “Every time I think about him, I think about how different it is for young people whose parents had, for whatever reason, a lack of vision for the future,” Clyburn says. “So every time I see him or read his opinions, I think, ‘That’s the difference between us. His indoctrination was to be less than.’”

Clyburn’s education was the opposite. His father once slapped him for cowering from an adult’s handshake and told him to always look people in the eye. The Rev. Enos Clyburn told his congregation, “No matter how long you’ve been down, getting up must always be on your mind,” the Congressman recalled in his memoir.

His father, Clyburn wrote, “viewed pessimism as a human weakness with no place in his faith.” It can be hard to believe in progress at a time like this. But to Jim Clyburn, there is no other way.

Source: Time

Powered by NewsAPI.org